P. Brad Parker: A Brief Vocational Autobiography

My vocation in life is investigating the elements of Greek Hellenistic sculpture with a view to developing a compatible artistic method. By Hellenistic sculpture I mean the body of work dating from the time of Alexander the Great to ca. 200 AD—a body of work that, building on the great achievements of the Classical period, took sculpture to new heights in the Pergamon Altar reliefs, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, the Venus de Milo, the Belvedere Torso, the Laocoön, and numerous other masterpieces.

This vocation has led me to see Hellenistic sculpture as a body of information to be read on its own terms. The underlying technique involves a language that is at first view open, simple, and inviting. Yet the language is sufficiently subtle and complex to have evaded the comprehension of—and indeed dwarfed the achievements of—modern artists from the Renaissance onward. The modern idea of “High Art,” in other words, is not static insofar as it derives from an evolving understanding of the sculpture of the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Astonishing as it may seem, a deeply informed understanding of the Greek achievement was shared only by an enlightened few even in Michelangelo’s day. It is shared by almost no one in our own.

A fuller understanding of this achievement, however, is truly crucial at the present time, when modernistic trends dating back to the first half of the 19th century (not to mention the overtly modernist trends of more recent origin) have wiped the slate clean of even a residual understanding of truly classical principles of form. As a result, the growing ranks of avowedly traditional artists in our midst display a seriously impoverished understanding of the human figure. The clean slate, then, represents both a formidable challenge and an enormous opportunity for sound artistic instruction. I believe a bold new foundation for formal pedagogy must be laid in the decades ahead.

* * *

After graduating from a Bethesda, Maryland, high school art program (admission to which was portfolio-based), I studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, generally considered the nation’s premier art school, from 1977 to 1984. The primary interest the PAFA held for me was its cast collection of antique and modern sculpture. I made this collection the core of my study throughout my years in Philadelphia. My time was mainly spent drawing and making clay sculpture copies of the antique and drawing life models. Concurrently, I studied at the Frudakis Academy under Angelo Frudakis Sr. for three years. There I had access to some high-quality modern bronze recastings of antique bronzes in the Naples Archeological Museum, which the University of Pennsylvania had loaned to Mr. Frudakis. At this time I made a conceptual breakthrough regarding the techniques based on late-19th-century training, then (as now) the “traditional” or “academic” norm. Following the tenets of this training, I realized, would actually undermine, rather than merely simplify, the language of Hellenistic sculpture.

Yet the realization that this formal language actually existed was critical to my development. I discarded eighty percent of my academic training and, having returned to the Washington, D.C., area, continued my studies on my own, making use of the collection of the National Gallery of Art as well as life models in working out an artistic method grounded not in superficial notions of “style” but rather in complex formal content.

This methodological quest took me to Europe, where I spent the years 1990-1994 studying Hellenistic sculpture. I also studied modern techniques derived from Hellenistic work, focusing on Michelangelo and those most influenced by him, particularly Giambologna and his school, as well as the French academic school down through Houdon, and the seriously underappreciated German classicists of the 19th century, who continued to produce superior work for decades after the French academy had gone into decline.

I spent most of my time in museums and archeology departments, drawing copies with charcoal or making sculptural copies in clay. This I did at the Budapest Technical University, home to a plaster cast collection as well as works of antique sculpture; at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin; at the Royal Collection of Plaster Casts in Copenhagen; at the Vatican and Capitoline museums in Rome; at the archeological museum in Sperlonga, Italy, which contains important remnants and reconstructions of the major sculptural groups originally installed in the famous Grotto of the Emperor Tiberius; and at the aforementioned Naples museum, one of the foremost repositories of antique sculpture.

For the student of Classical and Hellenistic sculpture, large European collections of high-quality plaster casts of antique works, such as the Copenhagen collection, are ideal venues. A fine plaster cast is actually preferable to the original sculpture for artistic training since its even, matte white surface reveals aspects of formal complexity easily missed in the actual work of marble, bronze, or terra cotta. This is why plaster-cast production began during the Renaissance in cities like Rome that already boasted major troves of antique sculpture. Unfortunately, the ranks of major cast collections have decreased precipitously—thanks largely to the destruction wrought in World War II, but also to the neglect and outright vandalism that modernism brought on over the course of the 20th century.

During my time in Europe, however, cast collections were being re-evaluated as significant art-historical resources. Salvaging of casts and their relocation to suitable exhibition space got underway just before my study tour began. As the information on extant collections in leading institutions was still limited, I decided to catalogue all the plaster-cast collections I could find, listing the name of the particular sculptural work, the museum where the actual sculpture in bronze or stone resides, and the degree of clarity in the plaster-cast reproduction.

This project took me to more than 70 cast collections in Austria, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Switzerland. Venues ranged from secondary art schools (licei d’arte) in Italy with small collections to a defunct paper mill in the tiny, industrially hyper-polluted Czech town of Hostinné. The latter venue housed hundreds of high-quality casts relocated from Karlova University in Prague on the eve of the Soviet suppression of the Prague Spring.

My listing of each sculptural variant in plaster is a guide to the highest-available-quality reproductions for making studies in clay or on paper. Some venues—most significantly, the Dresden plaster cast collection—were off-limits to me during this period, but my list nevertheless will serve as a valuable resource for future students of classical sculpture. This is all the more important in light of the fact that the major American plaster-cast collections were never of exceptional quality and are in their present state mediocre. American institutions have been unwilling as a rule to pay top dollar for high-quality casts.

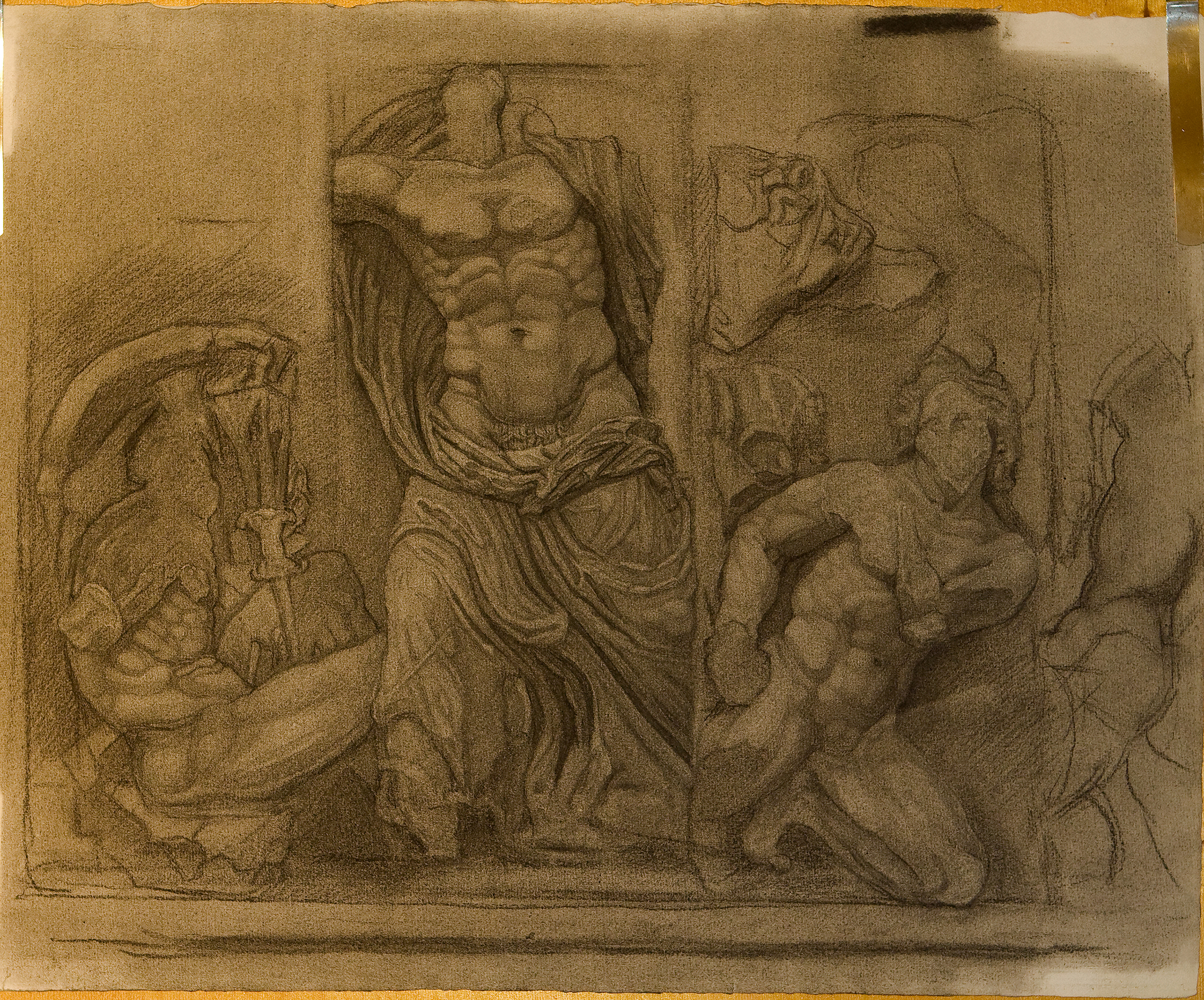

Farnese Hercules, Hellenistic sculpture in the National Archeology Museum, Naples, charcoal, by P. Brad Parker

Another important aspect of my European research was the study of pre-19th-century competition sculptures by advanced students at the major academies and ateliers throughout Europe. This involved discovering the formal elements derived from Hellenistic work that were taught by the leading artists and exemplified in the prize-winning student work. In proving their merit, these graduating sculptors would demonstrate their understanding of the formal content issues they were taught—in a manner less subtle and evasive than was typically the case with their masters’ work. This gave me a grasp of pedagogical issues that I believe has made me a much more effective teacher at my own school, The Parker Studio of Structural Sculpture, in Baltimore. Given my lack of access to a good classical cast collection, I largely rely in my teaching on just a few plaster casts of antique works which I acquired in Europe, or retained as copies I sculpted in clay and cast into plaster.

* * *

Pergamon Altar Relief, Hellenistic Sculpture from Turkey, now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, charcoal, by P. Brad Parker

My time in Europe also made me an infinitely better sculptor than I could have been otherwise. I have applied the knowledge acquired during my long, arduous self-education to sculptures ranging from portrait busts to mythological works.

My oeuvre reflects the Hellenistic sculptors’ understanding that each human body is different, endowed with its own unique topography. They set about extrapolating this topography from the model and clarifying it. The current “traditional” methodology is totally different: It involves a rather uninformed and generic rendering of anatomy, and is keyed to light effects manipulated to arrive at an “optical realism” or “optical record”—often topped off with a slick finish that can lend a deceptively classical aura. Though it relies on inadequately articulated shapes, this formal approach can play out beautifully in a photographic reproduction, with the sculpture carefully placed so as to exploit the incidence of light. Greek sculpture, in contrast, has nothing to do with light effects, and everything to do with complex geometric form.

Many avowedly classical programs currently involve defective artistic methods that arose after 1840 along with misinformed interpretations of earlier methods. These include the sight-size method and Bargue “shadow-shape” technique, which lead students to incorporate predetermined, more or less arbitrary shape content into their work along with proportional scale elements that are not only schematic but contradict the life model. Classical logic and practice are themselves contradicted by these photographically-oriented distortions of shape and content, and the dimensional aspect of form is degraded as well.

It is understandable that many people would see my work as “realistic” or even “naturalistic,” while associating classicism with the idealization of the figure. The error here lies in mistaking style for content. It should also be borne in mind that the idealization of the figure in classical Greek sculpture resulted from the use of numerous models of very similar physiognomy–something possible only in an ethnically homogeneous society very different from a melting pot like ours. The resulting transfiguration in top-tier classical Greek work thus transcended any particularized likeness. But this is a rather impractical aim in contemporary sculpture. Even Renaissance attempts at classical idealization often proved vacuous. By way of investigation I have employed multiple models in several of my figure sculptures, but have found it is not a procedure that lends itself to habitual application. Just having enough time with an individual model–as opposed to the contemporary practice of relying largely on photographs–is a sufficiently tall order.

Establishing a sound artistic methodology is of course more difficult nowadays because art history is understood as a matter of literary critique rather than formal appraisal in any true sense. The “narrative” thus takes on a life of its own. Greek sculpture, however, has a spiritual dimension that defies the current critical wisdom. This arises from visual and conceptual elements that enable the artist to transcribe not just a set of natural phenomena but a heightened experiential state.

The Greeks’ experience of nature, in other words, led to a quest for archetypes in which the various patterns they observed in nature were distilled and recast in works of art incarnating what Goethe might call an “intensified” or exalted reality. The activation of the surrounding space that the sensitive observer experiences in contemplating works of Greek sculpture—the Winged Victory at the Louvre is just one obvious example—is part and parcel of this intensified reality.

Great modern sculptors, Michelangelo above all, not only divined this ancient artistic teleology, but reconciled it with Christian belief, for in his view the beauty of classically-informed art was a token of heavenly things and the life of the world to come. Inevitably, then, the spiritual dimension within the classical artistic tradition is integral to my own vocation.