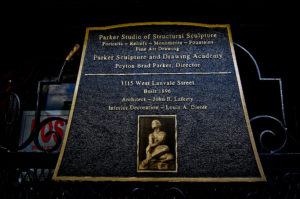

Study Sculpture and Drawing at The Parker Studio of Structural Sculpture

Parker Studio offers art classes in drawing and sculpture in our Baltimore studio space on Lafayette Square.

Check the calendar for an ongoing schedule, and click on the class titles for more Detailed descriptions. Detailed class descriptions also appear below.

Contact: 301 633 2858, or 443 764 5364 by cell phone call, or text message, or contact: [email protected] to arrange a visit, or to enroll in a class or open group. Message Board below seems to have issues. Calendar is general information on classes available, days and times vary.

Current and Upcoming Classes and Open Groups

OPEN FIGURE DRAWING AND RELIEF SCULPTURE GROUP | Parker Studio Structural Sculpture: Mondays: from 10:30 AM to 2:30 PM, also from 6:30 PM to 9:30 PM. Tuesdays from 10:30 AM to 2:30 PM, also from 6:30 PM to 9:30 PM.

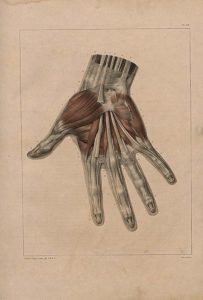

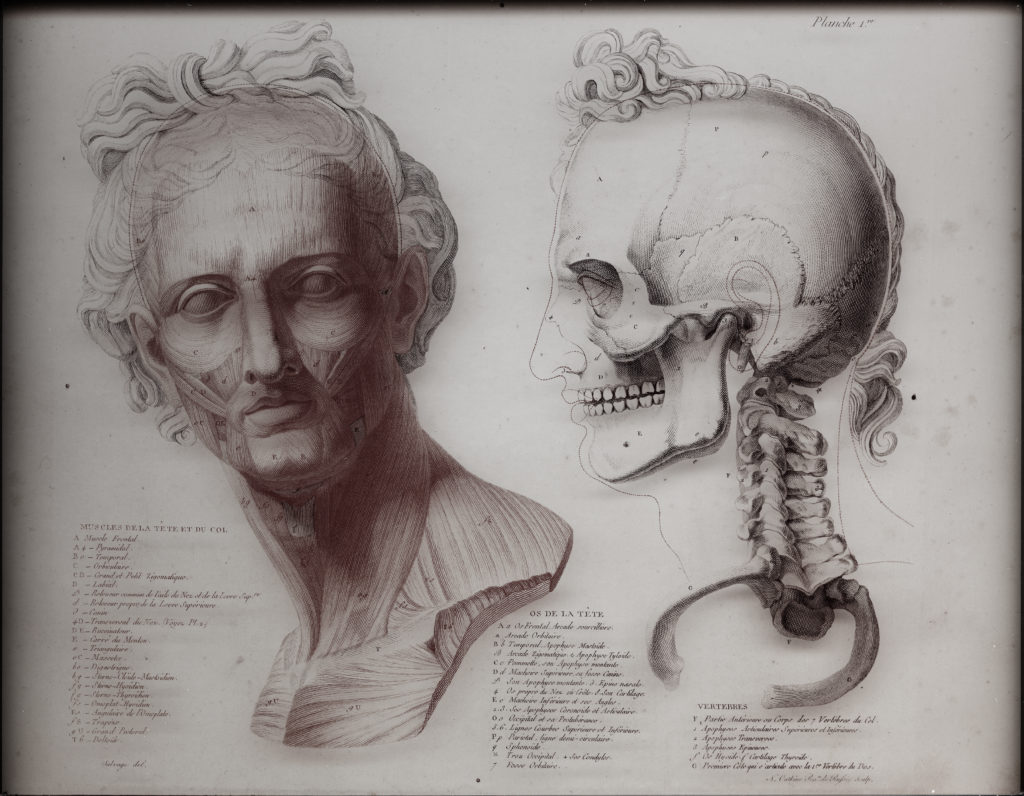

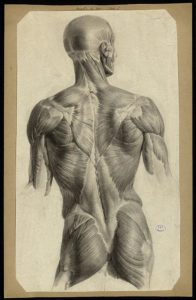

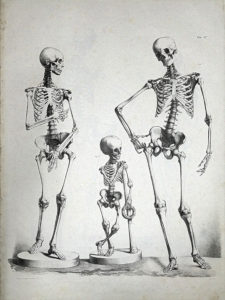

DRAWING COURSE – FIGURE & PORTRAIT MODEL / LIFE MODEL / ANTIQUE SCULPTURE / PLASTER CAST / ANATOMICAL MODELS / SKELETONS COURSE (parkerstudiostructuralsculpture.org) : Mondays: from 2:00 PM to 6:00 PM. Tuesdays: from 2:00 PM to 6:00 PM.

OPEN FIGURE SCULPTURE GROUP | Parker Studio Structural Sculpture : Sundays from 9:30 AM to 12:30 PM.

FIGURE MODELLO SCULPTURE COURSE: Fridays: 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM (evening session).

FIGURE MODEL SCULPTURE COURSE | Parker Studio Structural Sculpture: Fridays: from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM (morning session)

PORTRAIT SCULPTURE COURSE | Parker Studio Structural Sculpture : Thursdays: from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM (morning session)

PORTRAIT MODELLO SCULPTURE COURSE | Parker Studio Structural Sculpture : Thursdays: from 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM.

ANATOMICAL FIGURE SCULPTURE CLASS: Sundays from 2:00 PM to 6:00 PM. The first session to focus on the construction of an armature and will not count toward the requisite 13 classes. Optional workshop time for the Anatomical Figure Sculpture Class is Wednesdays, or before, or after Saturday / Sunday class session.

Open Drawing and Sculpture Groups

Join us for open drawing and sculpture groups, in which participants can work in our studio space and share the cost of a live model. Please call to arrange for participation. No instruction is offered for the Open Groups, and all levels of experience are welcome.

Follow these links for more details on the Open Figure Drawing and Relief Sculpture Group and the Open Figure Sculpture Group.

Classes in Drawing and Sculpture

Classes are private and by appointment. Students are responsible for the provision of materials.

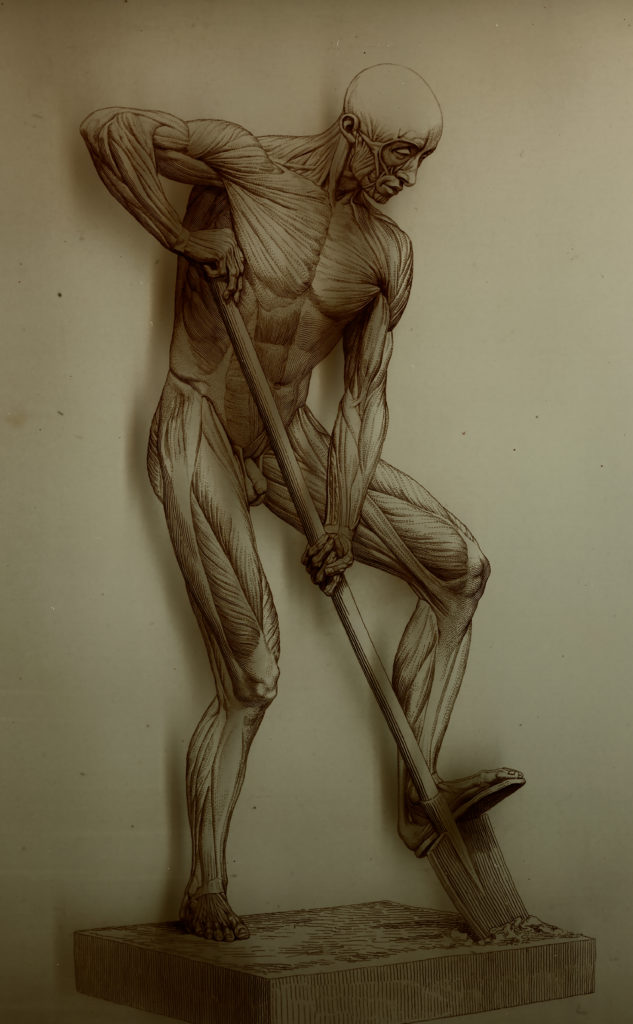

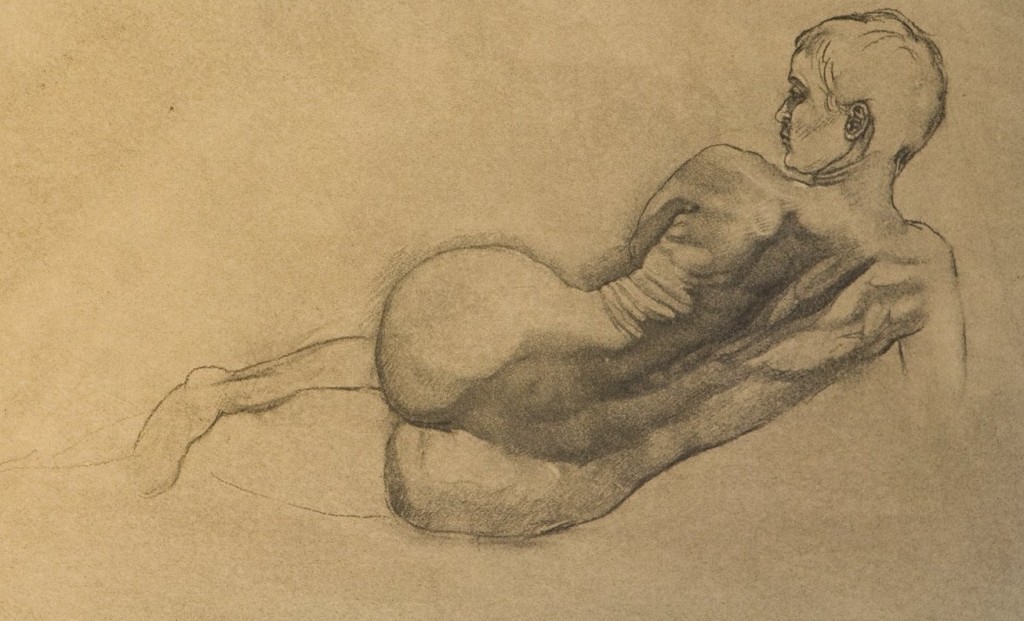

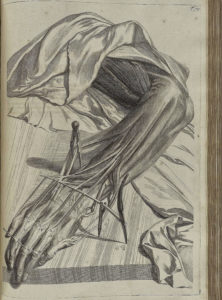

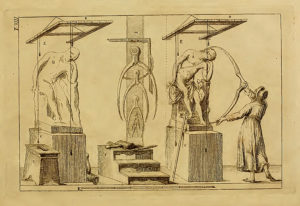

Anatomy Sculpture demonstration from class

BEGINNING COMPOSITION FIGURE SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course consists of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Figure Sculpture is each time for the duration of the course. Students will focus on bone landmarks and major muscle groups while working to capture the action of the pose and characteristics of the model. Overall forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated sculpture sketch composition.

Cost for the course:

$ 1120.00 for 9 – 4-hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for 9 – 3 -hour evening sessions.

ANATOMICAL FIGURE SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

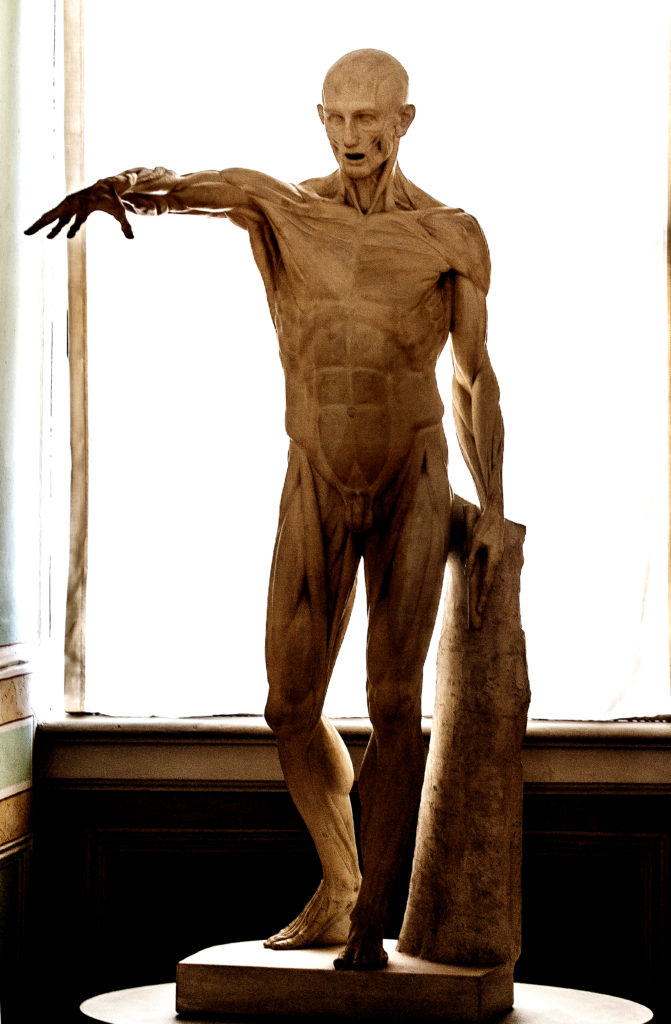

Third Floor Sculpture Studio Room, showing the Anatomical Collection, and Mastiff pup (pup not normally allowed in studio).

This course will be taught in four parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour classes (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Figure Sculpture each time for the duration. Working from the model, students will construct an ecorche with exposed skeletal and underlying muscle parts on one side and rendered surface muscles on the other. The first half of the course will focus on the underlying structure while, in the second half, students will work towards completing the overlying muscle masses. All skeletal and muscle shapes will be treated in a naturalistic manner, but with inherent shape content true to the model.

Cost for the course:

$ 1120.00 for each quarter segment consisting of 9 – 4-hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1120.00 for each quarter segment consisting of 9 – 3-hour evening sessions.

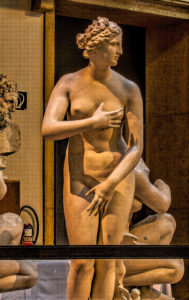

Muenchen Abgussmuseum Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerk, A small portion of the Munich Plaster Cast Collection of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture which consists of thousands of plasters mostly cast directly from new molds off the original sculptures. Collections of plaster casts of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture were started in Italy during the Renaissance in important art training centers. These plaster collections grew in size and importance as the High Renaissance arrived and the expansion beyond Italy for the serious education in art became more available. The plaster cast when of extremely high quality is preferable to the actual marble or bronze, utilizing these plaster casts to study Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture. The complex visual geometric shape orders are more easily discerned in a top quality plaster than the marble or bronze. This new recreated plaster cast collection reflects what were massive collections of plaster casts of Greek Classical, Greek Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman sculpture created during the late 17th. through the 18th. and 19th. century in Europe with the further introduction and development of Academies of art funded by the State, a few businessmen that funded collections, and starting in the mid 19th. century large archaeology department collections that started to form. Most of what survived in Europe now is associated with archaeology departments. Most of the surviving plaster cast collections associated with the various European art schools and academies are of very low quality. Large collections each comprising 5,000 to 9,000 plasters casts after antique also with some including pre-nineteenth century highlights of European sculpture was especially present in the Germanic, Scandinavian and French regions. The disbandment of utilizing the plaster collection of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture as the primary source of visual complex content to study and emulate built momentum in the early and mid 19th. century initially in the French art academies with the ill-informed optical record photo-inspired “Classical” realists, and Romantic period artists. The influence of the French Academy was dominant across Europe since the Academy system was first initiated in France in the late 17th. century and was the aesthetic, perceptual, as well as the mechanical implementation that most Academies throughout Europe based their own academies on. The movement in opposition to Greek/Greco-Roman visual content spread across Europe with the French Academy influence shift in visual content aesthetics and implementation of visual content from just before, during and after the period of Napoleon, then with the advent of incorporating early forms of photography as well as the further development of “optical record”as the framework for art in imitation of photography. With the later 19th. Century, early modernists, Impressionists, Secessionists et all expanded this movement away from Greek sculpture as anything more than a substitute to the life-model to learn how to copy tonalities and anatomy superficially. As well as the “anatomy realism” popularly credited of Rodin – though this banality had precedence long before Rodin – another “Optical Record” type. Later variants of Rodin’s lineage of superficial anatomy surface rendering bravado, have lineage mixed in from tonality surface rendering that at extremes are represented by “Open Form” bulbous marshmallow form anatomically distended to achieve manipulated theatrical light effects from afar, such as in Bernini’s sculpture and the lineage he represents, and “Closed Form” linear development of form utilized in a generic surface stylization after Greek sculpture also rendered after light effects such as represented by Canova and the lineage he represents. These are two examples from earlier schools of sculpture in opposition to Greek antique sculpture complex geometric orders of visual language content. Though as a bit of a farce both lineages from Canova and Bernini are credited as Classical Greek informed the credit being style not content. Another example is the “Work Shop Method” of sculpture – memorized per-ordained generic templates for creating a figure and portrait bust sculpture, utilized by a large percentage of historic traditional European sculptors – though the opposite of the influence from Greek sculpture. The “Work Shop Method” evolution is represented by the rather clunky Bauhaus, Soviet/Russian, Chinese Communist as well as typical “Photo-Classical Realist”, “Photo-Baroque”, “Photo-Renaissance” Russian, West European and American sculpture of the twentieth century and twenty-first century. All the idioms mentioned above often converge together in a pastiche mess along with “Optical Record”/photographic source. All of these lineages in opposition to informed Greek, early Greco-Roman sculpture continued after the period of Napoleon through the 19th. Century until now admixed with photographically inspired “Optical Record”. The next period brought the destruction of the plaster casts during the twentieth-century wars, and finally the purposeful destruction during the twentieth-century by the modernists of the majority remaining surviving plaster casts of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture. The reformation of plaster casts of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture that has occurred since 1989 has little to do with contemporary art trends and more a concern of archaeology departments within European universities and State institutions. Thankfully the contemporary visually and intellectually uneducated artist that comprise our period are not intrinsically involved in this re-establishing culture, history, aesthetics, and visual content heights of achievement displayed to the public with these re-established collections. Some directors, head of departments housing the revived plaster of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture that have an agenda to contaminate and degrade the content toward a contemporary art cause have unfortunately established themselves. Contemporary architects with a modernist background have also messed up the damaged surviving or a total rebuild from destruction of architecture in restoring what was built in the nineteenth century to house these collections. Though it is commendable that serious Classical study in architecture has been initiated in some institutions toward re-establishing public and private architecture to a higher level in contemporary times, the education is in contradiction to an understanding of the hallmark Greek and early Greco-Roman sculpture and the heritage of it in the best European sculpture. This is also evident in the United States in the Beaux Art Classically derived nineteenth and early twentieth-century architecture that is quite impressive though a disconnect with the equivalent sculpture content. The “Optical Record” sculptors commonly have bastardized schematic geometry composition motifs that converge at an extended crossing, like a signpost flapping from a hinge with a cross line arrow – often multiple converging cross-line arrows – pointing to the junction in case one might miss it otherwise. This cross-point juncture is often at the most ridiculous convergence – such as the end of a pointing finger, an elbow endpoint bent in a similar manner to a chicken dance or similar point endings of the subject or subjects that imply the aforementioned “signpost flapping from a hinge”. Compositional geometry of the “Optical Record” artist often supports the sophistication implied of monkeys jumping along arched lines – their bodies and appendages curving exactly along the axis edge or somewhat glued to the axis lines. Usually, a multitude of these types of alignments occurs throughout a composition so as to prove the thoughtfulness of the artist. Like placing cutout paper dolls a little girl makes joining at all the fingertips of each hand. The effect of the “signpost flapping from a hinge” as well as the concept and effect of two-dimensional schematics utilized in three-dimensional sculpture is a work of sculpture that looks like a cutout to only function from set two-dimensional viewpoints apart from the trivialization of the alignments. Again this is a byproduct of the influence from photographically or “Optical Record” derived artwork. { The composition relevance to Greek sculpture and it’s heritage incorporates – elements that build on each other in order to arrive at a surface that reflects the figure’s topographical structure as well as its external solid projections in the sculptural composition. The specific “Static Faceted Tectonic Shape” expanded as a schematic though usually only part of this shape is within the composition, creates a framework for the pose placement and composition of the whole sculpture together and contrasted with the characteristic shifting “Spiral Rhythmic Turning Planes” expanded to the composition motif. The other two main aspects are the specific “Interlacing (or Fingering) Planes” set at “Commensurate Planes” at positions to achieve “Optimum Attraction of Masses” expanded to the composition. The composition, in turn, is situated within a geometric envelope or “Platonic Solid”, or within a fraction of the “Platonic Solid”, or related three-dimensional geometry generated by the Golden Proportion (a proportion closely associated with the Fibonacci series).

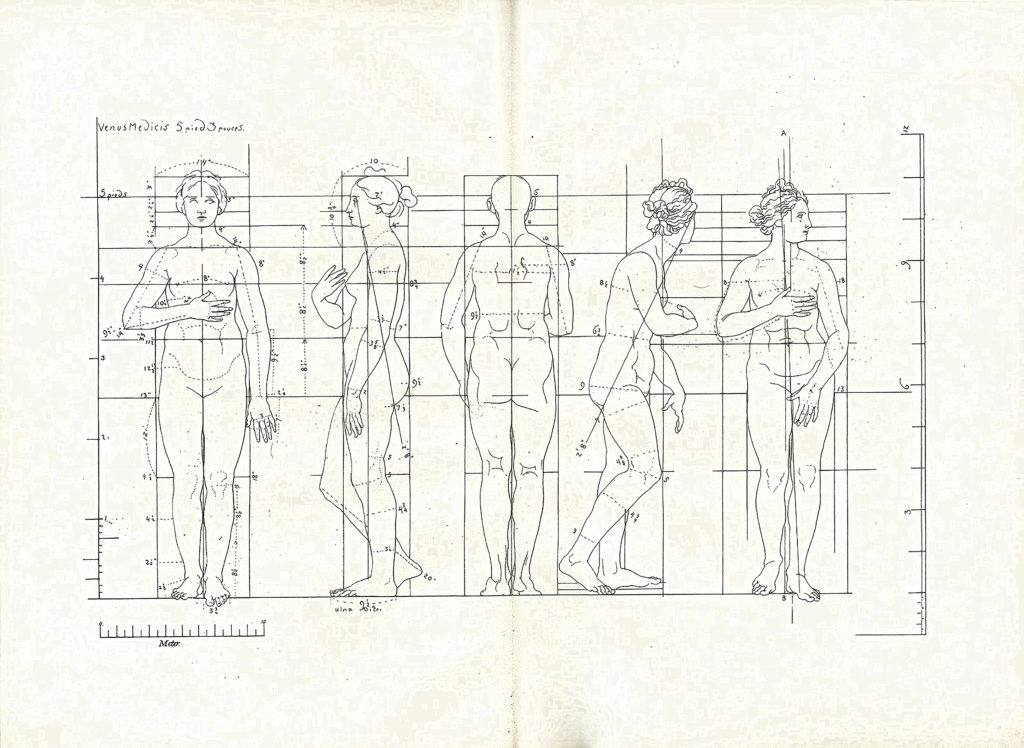

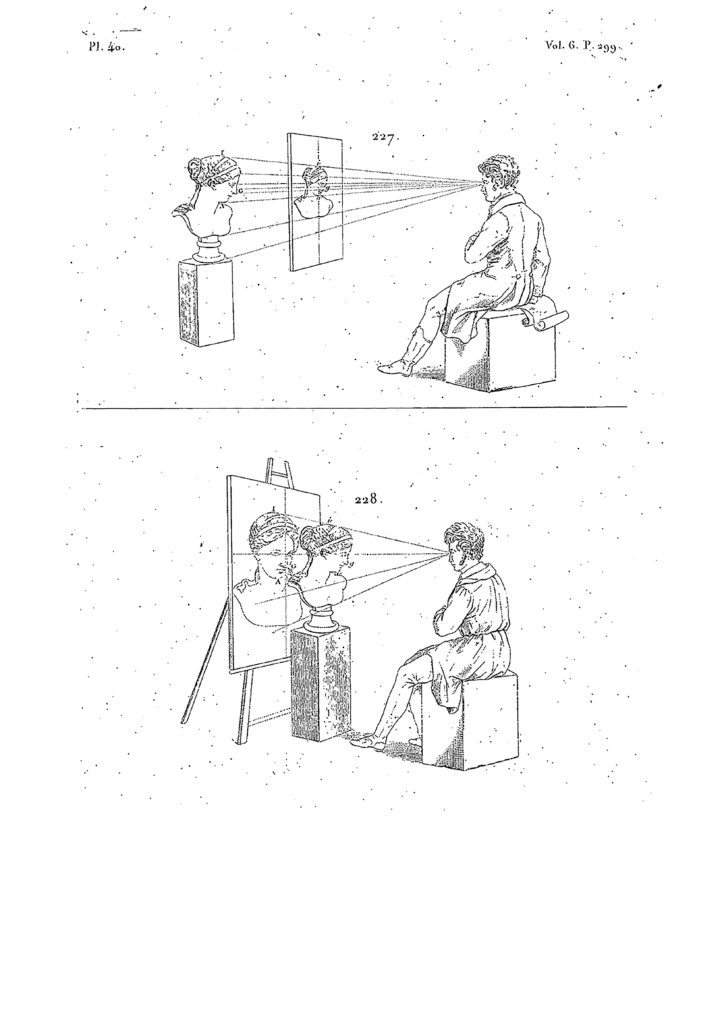

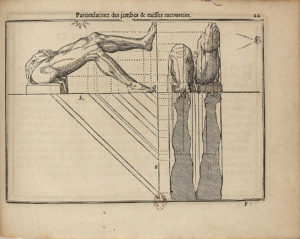

The sculptural composition’s enclosure within the “Platonic Solid” is selective and indeed partial rather than schematic and complete, generating a vital tension. The individual subject taken from nature is thus combined with the Platonic Solid in a manner that subordinates the latter to the “Geometry of the Individual”, as inflected by and extended within the composition. – from: description-visual-concepts-associated-hellenistic-sculpture/ } The “signpost flapping from a hinge” is in compliance and complimentary with the artificially condensed depth of field tonality rendering extracted from “Optical Record” visual language then expanded – forced outward in an unsuccessful theatrically rendered light effect to attempt to appear spatially extracted as well as disguise the frozen moment. The frozen moment extracted from the anti-movement caught in either the photograph or the perpetual habit of vision of the “Optical Record” artist is like a walking gesture of a person whose legs would break and interrelated body alignment movement contradict if forced into a progressing movement that a photograph and “Optical Record” developed image reflect and imply. Sometimes the referenced monkeys jumping along arched geometric composition lines are exaggerated as well in an implied forced movement impossible to make sense of in any harmony or potential logic in an attempt to disguise the photographic dead end counter to movement. Often the implied gestures of a figure or figures have extended themselves beyond any return in the process to the next movement position semblance – another aspect of anti-movement incurred by habit as an “Optical Record” or direct extraction photographically or as is more common now with video source of a life-model all in combination or singularly from the artistically retarded practitioner. The opposite end of the spectrum treatments for the figure range to a storeroom dummy generic version or variant of a Classical, Hellenistic, or Greco-Roman sourced sculpture imitating the original as a contemporary work though without any of the visual knowledge necessary to rise above a work worthy of wearing a piece of clothing in a store window. Also the industrial design movement for portrait and figure art in the 19th. century for drawing, painting, and sculpture – for the remaining idiots not elected to attend a higher education in the top Academies of Fine Art to train these leftovers to fulfill commerce – the industrial design method that later found it’s inheritance in the Bauhaus and it’s offshoots. Static shape based on tonalities placement in sculpture is the equivalent to “Shadow Shape” in a drawing. The “Shadow Shape” line is a zig-zagging outline separating the shadow from the light region in a figure, portrait, or such of the subject within a drawing. This treatment has nothing to do with complex shape orders – it is a mechanical replication of the shadows and light. As such the same description occurs in either a photographically extracted or “Optical Record” artists sculpture. It’s a similar manner to the beach artist working on a black velvet pastel portrait. Another attribute in the extraction of light/shadow imitation are the attributes of stained glass sectional shape areas – which appear as abstracted static tonal segments – flattened tonal schematics in opposition to anything approaching complex shape derived from the life-model as in the case with Greek sculpture heritage in sculpture method. Proportion and scale are also often greatly out of wack in “Optical Record” artists especially post WWII up to our contemporary sculptors – if not overly obvious to the uneducated layman on a visually educated viewing misappropriations are abundant with sculptors sculpture and drawings, the same is evident in “Optical Record” painters of which all the mentioned deficiencies included. Below further on this posting page is a simple representation from “Johann Gottfried Schadow” lesson drawings demonstrate foreshortening rules of proportion that proportions are interrelated and constant, remain true to the actual measured elements and not distorted contradicting interrelated scale as would be the case with perspective from angled viewpoints or habitual ignorant misappropriations of scale by the typical “Optical Record” artist. In Hellenistic as well as early Greco-Roman sculpture in the higher tier examples often scale and proportion are manipulated – a significant influence in the “Mannerist” and “High Renaissance” periods. Though this manipulation of scale and proportion in Hellenistic sculpture is wholly unrelated to the “Optical Record” artist sculpture and drawing bastardizations developed from ignorance and misconceptions. Even “Sight-Size” practiced by many contemporary “Classical Realist” in drawing and painting is usually part of the venue of the contemporary figure and portrait bust sculptor. A further description of “Sight-Size” – “Sight-Size Traite Complet de La Peinture par M Paillot de Montabert Planches Paris 1829” is explained further down this posting page with a descriptive accompanying illustration from the early nineteenth century. It seems, in general, the contemporary “Classical” architect is thrilled to familiarize themselves in appreciation with all these habits or learned discourse of the “Optical Record” artist as proof of their – the artist excelled genius. The “Lincoln Memorial”, Washington D.C. – Abraham Lincoln statue by Daniel Chester French is an example of misappropriations in scale, parts, and shape orientation that inhabit the work as Dr. Frankenstein would be proud. The small scale model was pretty awful to begin with from Daniel Chester French for his seated Lincoln. D.C. French’s small scale model has hands that appear more prominent than anything else on the sculpture, with modernist treatment of expressionistic contortions of the left thumb, as well as knuckles independent of the hand, and hands that even in the small scale sculpture look dis-attached to their respective arm-sleeve arms. The whole appearance of the small scale sculpture is a modernist realist treatment following in the tradition of contortions and optical record habits. With the completion of the sculpture in marble, parts were carried out as a redesign by the Piccirilli Brothers. From the base of the neck at the collar down to the knees one of the Piccirilli brothers is responsible – this though being “optical record” in development as well as the portions by D.C. French – this neck to knees is the best part of the Seated Lincoln sculpture. From the knees down to the feet another Piccirilli brother is responsible for the design, and from the base of the neck to the top of the head, as well as the hands and arms D.C. French is responsible. The head when viewing the actual sculpture at it’s placement site hover dis-attached to the neck and body – as also the hands are floating unattached to the arms. The content of form is very stilted – photographically oriented – optical record type development. As well as unrelated modernist treatment of the hands as some kind of mismatched statement flourish by the sculptor. The building though is quite nice and the interior setup for the sculpture benefits this contortion of a sculpture work beyond it’s value. The general public love Picasso, Rodin, Stalinist propaganda style sculpture – now referred to as “Classical Realism”and love anything trite they are spoon-fed. Perceptually the public as well as artists since 1860 gravitate to “optical record” modernist genre art of little value. So to claim the public naturally respond to a public monument because it “is great” or a natural response to a monumental sculpture work proves its worth – seems nonsense. Very popular in contemporary Classical-Realism is the draw and paint by number method – photo copyist artists following after Bargue-Gérôme Drawing Course (Cours de dessin) which produces results with almost no effort and any idiot can look like an expert – once one joins the mimicking superficial vacuous aesthetic as a goal. A photo copyist painter from the nineteenth century is greatly admired by contemporary photo-copyist, the painter – Photo-Classical-Realist William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Most of the late nineteenth century sculpture of Classical-Realism as well as contemporary sculpture utilizes this same basic method premise.

Another aspect of Optical Record sculpture is “Ballooning fields of unified shape”. The “fields of shape” are condensed as a photograph depicts compressed tonalities and out of this appendages appear, or the roll of a large stomach together with tons of fabric, legs, an arm, a hand, maybe several fused together figures – but all arriving out of a common mush of an exaggerated tonality. All appears significant, as though a great movement is taking place. or some contrived photographic flattened gestalt, but actually the static quality in this artificial farce is what is most striking. This effect is typical in much of second half-nineteenth century American and French sculpture. The “August Belmont” statue by John Quincy Adams Ward – the unity of a tonal field gestalt is the main shape of the sculpture – an aspect of tonalities as derived from spatially condensed photography “Ballooning fields of unified shape”. Jutting shapes protrude out of the static condensed mush of tonalities. The tectonic attributes arriving at his impressive realism are carefully articulated as Norman Rockwell would carry out with photographic slides projected onto a screen to copy as larger or smaller scale as well as an alternate solution to the problem of not knowing how to make a sculpture in Greco-Roman heritage terms. The art development process of Norman Rockwell is based on nineteenth century art method from painting, drawing, and sculpture going back in some cases to early precedents of photography in the late 1840s in France, even earlier in transfer copy methods arriving at similar visual problematic results discussed here previously {A further description of “Sight-Size” – “Sight-Size Traite Complet de La Peinture par M Paillot de Montabert Planches Paris 1829” is explained further down this posting page with a descriptive accompanying illustration from the early nineteenth century}. The client, commission, or self determined art project would be carried out with photographic media, and or the equivalent of slides projected onto a screen – the many photos of the subjects along with a more minor attribution utilizing the client or life-model in studio as a secondary source to fill in further detail, as well as seeming credibility working a little bit from life. The combination of figures together with clothing making a composition is not unusual in earlier pre-1800 sculpture, but it has none of the condensed field of tonalities that are seen in the photographically imitated effect. J. Q. A. Ward’s sculpture of Matthew Perry statue, Touro Park, Newport, Rhode Island is another combination of static realism of Optical Record mixed with memorized rote structural templates combined with “Ballooning Fields of Unified Shape”. His Smith Memorial Arch, Philadelphia – the horse and rider are fused as a charcoal tonality drawing made from a photograph – the rider and horse are a single unity shape – “Ballooning fields of Unified Shape” with appendages projecting outwards. It’s a striking two dimensional outline from formal specific viewpoints – but the effect of a charcoal drawing depicting fields of tones after a photograph are static and as such arrive at this stilted sculpture technique. Though as a method of manufacture in an assembly line way it’s extraordinarily efficient. Essentially all of Wards sculpture has attributes of this along with before mentioned “Optical Record” traits. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Deacon Samuel Chapin Monument (the “Puritan”), 1887, Springfield, MA.and Augustus Saint-Gaudens Adams Memorial” – Rock Creek Cemetery (Washington DC) are extreme versions of “Ballooning fields of unified shape”. The “Ballooning fields of unified shape” portray what looks dimensional to a novice but are actually in opposition to dimensional shape and is not spatially supported organic complex shape as depicted in the best Greco-Roman sculpture lineage. Saint-Gaudens and J. Q. A. Ward had many assistants and students who carried this aspect of photography and composition forward into future generations. Many other sculptors in France, Italy, and the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century were exponents of this “Ballooning fields of unified shape”. This effect of condensed artificial tonalities is extremely attractive to the contemporary viewer – often preferred to pre-modernist and pre-contemporary sculpture, since so much of a sense of comfort derives from the predictable and artificial photographic source.

A few Greek and Greco-Roman plaster collections were already taken over by the Modernists in the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century with a cause to include Contemporary sculpture of the rubbish occurring during this period. The examples in past history here in the United States of plaster cast collections of Greek Classical, Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman sculpture were primarily a lower quality rendition plaster from the original sculptures imported from Europe as less expensive later pulls from a mold after the detail and integrity of complex form had diminished – thus a cheap price. Also, the Caproni Brothers supplied lesser quality plasters within the United States, which were from molds they brought over with them to supply the demand for cheap plaster casts to an unsophisticated client, or institution. Some higher quality plaster of antique in the United States was purchased from German companies prior to the nineteen thirties though these were not generally housed in institutions with a purpose of utilizing them for sculpture copies in art training. Generally, the Germanic companies that produced plaster of antique were superior to other plaster companies during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. These plasters that have survived or have been rescued from improper housing over the years that are available to view in Europe are in some collections very good quality detailed plaster casts, generally in the United States the retrieved collections from decades of storage now have little evidence of the original quality to show if any were of the highest quality at an earlier time period. Houdon had sent his life-size Anatomical Man – L’Ecorche 1767 – a plaster copy of high quality to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, in addition to Napoleon sending a small group of plasters to the same institution for art training. The teachers and students smashed – destroyed the plasters from Napoleon and Houdon as a modernist political statement in the nineteen fifties along with thousands of additional plaster after antique and European sculpture purposely destroyed that formed the collection at the PAFA. This political movement against traditional training and art, even though the training had long ago disappeared in Europe, and essentially never existed in the United States – took place all over the United States with most collections of plaster casts destroyed, thrown away into trash dumpsters, or just disbanded and disappeared to now an unknown history. In Europe, this political movement happened in the academies of art earlier in the twentieth century, the United States art teachers representing the most extreme modernist came into power later than Europe. At the PAFA it’s doubtful that these plasters after antique had continued as quality reproductions though since every year or so as the walls were painted so were the plaster casts going back to the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth century. A few of these plaster was replaced by donation with second rate plasters that were also painted every few years along with the same wall paint. Previously the plaster collection in the PAFA in the nineteenth century had thousands of plaster casts though of very mixed quality. When I was a student at the PAFA in the late nineteen seventies to the mid nineteen eighties the remaining surviving plaster collection numbered between one hundred or slightly more. During my last year or so the PAFA inferior remaining plaster casts covered in a thick coating of a multitude of wall paint including the lower quality replacements were “restored” by a group of student imbeciles that were paid to scrub down the paint with an emulsion to disintegrate the thick multitude of layered paint which took down any remaining inference of complex surviving turnings to a general soft rounded generic form. Then the students were directed to repaint again to make a nice fresh generic off white which doubly filled in the undercuts of any remaining form. This collection though was one of the few remaining in the United States, along with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in N.Y.C. plaster collection – mostly worthless damaged plasters that had been stored under a bridge in a leaky warehouse in N.Y.C. for decades disintegrating the plasters with direct water and moisture. The Metropolitan plasters were later exhibited at the Queens Museum, as well as the more recently founded in the nineteen-eighties – New York Academy of Art. The restoration in the 1980s on the New York Academy of Art Met plasters included sandpaper to make a smooth formless even surface on the plasters. Other collections exist at the Springfield Museum, Massachusetts, the Lyme School, Lyme, Connecticut, Harvard, Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York, Austin, Texas University, and so on – all predominantly of damaged goods or initially mediocre to middle-grade quality. More recently the production of plaster of antique is produced from 3D digital computerized reproductions which have all the attributes from the photo-derived process, thus counter to a productive source to seriously study. Restoration carried on by essentially untrained artists working by reference of photography to the original sculpture or just by merry ignorance on the surviving plasters since the nineteen seventies have only degraded further any surviving attributes that might have still been present. The lower quality plaster casts of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture in the United States history equates with the lower quality rendition of the American artist and their education in the 19th., 20th., and 21st. century, apart from the import of the modernist cult and “optical record” doctrines with those returning American artists after their sojourns to study in Europe during the mid through late 19th. century as well as the “Classical Realist” and other venue training/artists in the 20th., and 21st. century. The surviving plaster cast collections here in the United States are primarily of low-quality now and most essentially useless apart from tonal replication practice exercises (optical record exercises that could be a lampshade post or a sculpture that lacks content) for drawing, painting, or sculpture – without any of the clarity in attributes – complex visual geometric orders content of the Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture – present that determines their significance. Goethe in his Italian travels – 1786 to 1788; “Italian Journey” visited many of the leading artists, and training with a few in art enough to have some practical basic understanding of visual content. Goethe’s interest after a deeper knowledge of Greek sculpture brought his travels as well to the collections of Greek sculpture and plaster casts. Goethe visited the Antikensaal in October 1769 where high quality plaster casts were made from the original Greek sculptures by Manelli exhibited at the Mannheim Academy ‘Hall of Antiquities’. This visit by Goethe to the Antikensal in Mannheim was the first exposure to full works of the many most famous of his day Greek sculpture realizing the breadth of the actual masterpieces. It appears the Ferrari brothers plaster casts of antique had not only supplied the “Gotha Dancing Faun” to Duke Ernst II, for housing in the Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Thüringen and the larger percentage of the early German collections including Göttingen University. The Leipzig art dealer Carl Christian Heinrich Rost also supplied the Ferrari brothers plaster casts for many other German collections of plasters after Greek sculpture. But it seems also the Ferrari brothers supplied many Italian art academies beyond just the “Gotha Dancing Faun” for the Accademia di Belle Arti di Ravenna, La Gipsoteca dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Ravenna. As Christian Goittlob Heyne, as well as many later more informed German collectors, realized the Ferrari brothers supplied poor quality plasters to their collections during the late 18th. and early 19th. century. It appears the same source with the Ferrari brothers supplied the academies of art in Italy for their plaster cast collections after antique during the period. This was also my experience – that the quality of the plaster cast collections was predominantly awful with a smaller proportion barely passable to mediocre in quality when visiting plaster cast collections throughout Italy in Liceo, Istituto Statale, archaeology department collections, academies, commercial vendors of plasters after antique, etc… An archeologist at Göttingen University – Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (Göttingen Archäologisches Institut) Christoph Boehringer in a meeting I had in 1991 with him on my research of the plaster casts throughout Germany, and Europe referred to a plaster in his Göttingen collection as the “Gotha Dancing Faun” presumably cast by the Ferrari brothers for the Greek sculpture plaster collection intended for Russian Catherine the Great. Christian Goittlob Heyne initiated the Ferrari brothers to supply portrait busts for the Göttingen University during 1771 and later acquisitions of well known Greek sculpture full figures between 1772 through 1775. The “Gotha Dancing Faun” was lost in transit from Rome to the Russian Czarina. A casting though was made for Duke Ernst II, for housing in the Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Thüringen collection by the Ferrari brothers mold makers during a stopover in Gothe en route to Russia. Professor Boehringer was not aware of any other surviving copies apart from his Göttingen collection plaster of the sculpture, as well as no original surviving in Rome of the “Gotha Dancing Faun” which was lost in transit to Catherine the Great in Russia. Later while visiting every collection throughout Italy of the time I discovered another plaster of the same “Gotha Dancing Faun” in the Ravenna Academy of Fine Art (Accademia di Belle Arti di Ravenna, La Gipsoteca dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Ravenna) cast collection. Both plaster casting in Göttingen and Ravenna was very low in quality detail and clarity but did give some indication of the general aspects of the marble original. Professor Boehringer was quite generous in his knowledge and in forwarding introductions for my arranging meetings with other directors of cast collections of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture.

Christian Goittlob Heyne apparently at a later time after exposure to the Dresden Greek sculpture castings suspected the Italian castings were lesser secondary castings made by the Ferrari brothers purchased for his Göttingen University collection. In Genoa, the “Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti” prior to WWII had an important collection which was almost completely destroyed during the war, as was the case with many collections. Though the remaining small number of surviving plasters were some of the better quality examples in Italy. These surviving plaster after Greek, Greco-Roman, and a few European period works were moved to the adjoining museum out of the Academy of Fine Art after students had started damaging in disrespect the plasters just prior to my visiting in the early 1990s. Often the better plaster casts in sheer number, as well as reproduction quality, greatly improved further north of Italy as exist today as well as what was present in the late 18th. century through the 1930s. Access to the actual sculptures for study by artists during Goethe’s travel would have been limited with the Farnese collection residing in Parma until 1787 when they were moved to Naples, but also the various spread of the actual sculptures beyond this as well as the difficulty in access to the actual sculptures to make serious long term studies in clay, and of less intensive study in drawings. A limited number of sculptors throughout Europe concentrated on study directly from the antique – spending six to twelve years as a last phase of the main education copying after Greek Classical, Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman sculpture. The larger portion of study from early teen years through late teens to the mid or late twenties incorporated study after plasters or the actual sculptures, in addition, to study after life subjects but this would have been preliminary study prior to a mature second study. This second study is what separates the majority of lesser artists from the smaller percentage of artists attempting a higher order of art. The second study generally occurs in a concentrated period, but usually continues throughout the artist’s life. The slavish copying after tones, arbitrary anatomical stylization imposition, unfortunate unintended comic or comic book like shape delineation, an artificial style that contradicts and is in opposition complex visual content, superficial likeness, too many impoverished variants of art to list here – is what occurs more commonly and is in opposition to an informed study. Much of the less serious study after Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture portrayed more of the unfortunate habits of imposed stylizations, a shortcut in a pretense of accomplishment out of ignorance resembling the actual Greek sculpture enough as to trick the unsophisticated compatriot artists, general public viewer, or patron. This condition of content derived from an informed understanding of Antique Greek sculpture was generally superior previous to the 1790s/1820s, though the plaster cast collections broadly expanded during a later period in contradiction to when photography became the template of art – with added artistic junk building atop this photo template as the 19th. century proceeded. The best of historic European sculpture though is a weak imitation, a lesser art form when compared to the best of Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture.

______________________________________________________________________________

Pergamon Museum Berlin – Male Torso – Hanging Marsyas fragment, Greco-Roman

Hanging Marsyas would be paired with Uffizi, Florence, Italy – Scythian – Turkey, Plaster

Charlotte Schreiter

Moulded on the Best Originals of Rome. Eighteenth-Century Production and Trade of Plaster Casts after Antique Sculpture in Germany

in: Eckart Marchand, Rune Frederiksen (Hrsg.), Plaster Casts: Making, collecting, and displaying from classical antiquity to the present, International Conference at Oxford University, 24-26 September 2007 (Berlin 2010), 121-142.

https://www.academia.edu/9815534/

In: Eckart Marchand/Rune Frederiksen (Hrsg.), Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting, and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present (Berlin 2010), S. 121-142, 2009 Charlotte Schreiter

Excerpts from publication:

“In 1794, a catalogue was published entitled Casts of antique and modern statues, figures, busts, bas-reliefs moulded from the best originals in Rost’s art dealers shop in Leipzig

(Fig. 6. 1). It listed fifty-four full-scale statues and seventy-five busts as well as numerous small-scale copies and “study pieces” – single hands, feet, monuments and reliefs among others. Fifty-six separately bound copper engravings illustrate a representative range of the most important pieces. This was the first time that the Leipzig art dealer Carl Christian Heinrich Rost (Fig. 6. 2) had published an illustrated catalogue of all the casts of antique and modern sculptures available in his shop.” 2

“The most important pieces were presented in outline drawings. The reduction of the figures to outlines corresponds to Winckelmann’s belief that these constituted the essence of the statues themselves. 4 Short explanatory texts specified the art historical importance of the individual antique sculptures. References to respective museum catalogues and commented catalogues – such as Casanova’s Discorso sopra gl’antichi 5 – emphasize the aspiration to seriousness. The artist commissioned to carry out the drawings, Schnorr von Carolsfeld, was chosen carefully: he was engaged upon the recommendation of the Director of the Leipzig Academy, Adam Friedrich Oeser. 6 Not wishing to provide a mere sales catalogue, the publisher (Rost) explicitly presented himself as a patron of the fine arts: He stated that he had not spared himself any effort to obtain the casts of the best antique artefacts in order to offer them to connoisseurs of the fine arts at a reasonable price.”

7

“Around 1770 the small range of existing plaster casts was commonly regarded as a lack. Hence, Johann George Sulzer postulated in his Allgemeine Theorie der Schönen Künste […] of 1771, that all academies should have a complete collection of the best antiquities. According to him, the only reason why this had not been the case was that the permission for taking moulds was too often refused.

13 Goethe’s personal reports document the alternatives available. According to him, sculptural works had been hard to find during his youth in Frankfurt. Only later did Italian plaster moulders arrive, bringing with them original casts, making new moulds and recasting them. These casts were obtainable at a fairly low price, so that he was able to build up his own small collection. 14 Since 1707 the Düsseldorf Electoral Prince Johann Wilhelm had started to compile a first class collection of casts taken directly from antique originals. 15 Conte Fede – himself a renowned collector – acted as his negotiator in Rome. He had access to the collections of the Medici, Borghese, Ludovisi, Odescalchi and Farnese and had permission from the pope and the Roman Senate to produce casts from statues in the Capitoline collections. The casts were made by Manelli. 16 A first delivery arrived in Düsseldorf in 1710. Because of the serious difficulties in transporting the plaster casts without damaging them, the decision was taken to deliver the moulds rather than the casts to Düsseldorf. This is one of the few cases in the eighteenth century in which one can be sure that the moulds sold in Germany were taken directly from the originals in Italy. 17 By 1714 the collection had grown to between eighty and one-hundred pieces. 18 In the middle of the century the collection was transferred to the Mannheim palace 19 and then again in 1767 to the specially established Antikensaal at the Mannheim Academy (Pl. 6. A). The moulds were also finally housed there. 20 This ‘Hall of Antiquities’ served not only as a classroom for art students, but also as a source of models for copies of antique statues for the park of the Schwetzingen palace. Thus, the reconstruction of the inventories reveals a representative spectrum of casts taken from antique statues, in no way ranking below that of other European and Italian collections. 21 Surprisingly enough, however, only a limited number of further casts was produced from them, most of which were intended for the requirements of the Mannheim court. The

Antikensaal rapidly gained wide renown and the numerous reports in various journals of the day reflect strong interest in it. Hofmann and Socha have compiled the contemporary sources on the

Antikensaal. 22 Among them the very first one in Meusels Miscellaneen artistischen Inhalts is important, since it lauds the just opened hall in a relatively widespread public medium. 23 Goethe visited the Antikensaal in October 1769. His report of the visit, that impressed him deeply, has become famous. 24 There, he was for the first time confronted with a large number of casts of complete sculptures. 25 The casts left a profound impression on him, that he revised only when he came to know the originals on his journey through Italy. Before then, he had never seen Laocoön together with his sons even though he possessed a bust and had seen the single figure of the father in a cast in Leipzig. 26 For a certain period, the Mannheim Antikensaal, with its restriction to plaster casts, remained a solitary case. Other princes in central Germany took antique artworks out of their ‘Kunstkammer’, supplemented them with appropriate acquisitions and completed their statue galleries – partly with plaster casts after antique sculptures. Among them, Wörlitz is one of the earliest examples and certainly the most coherently designed. Following the English Country House model and built in the Palladian style, the Wörlitz castle is one of the first neo-classical castles in Germany.

27 Prince Leopold III Friedrich Franz of Anhalt-Dessau had met Bartolomeo Cavaceppi in Rome in 1766.

28 Shortly afterwards Cavaceppi was commissioned to build up the collection of antiquities for Wörlitz. Not only did he have control over acquisitions, but also over supplementing, restoring, copying and providing antique sculptures. 29 The reference to English models was not limited to the architectural design, but also comprised the collection of antique sculpture which included antique originals as well as copies. Cavaceppi, who had numerous clients in England, was well versed in this process. 30 As a result, an overall concept could be developed which was groundbreaking for the German neo-classical style. In Mannheim and Wörlitz a single Italian representative had been responsible for the acquisition of casts and antique art. Yet not every court was able to commission a Conte Fede or a Cavaceppi. Courts such as Gotha, Kassel, Rudolstadt and Weimar had to use different sources (Pl. 6. B). The purchase of casts was generally connected with the founding of smaller academies of arts. 31 Some of these ancient plaster casts have survived at these sites. The example of Gotha offers an exemplary sequence of purchases: Between 1771 and 1773 Duke Ernst II commissioned Jean-Antoine Houdon to sculpt portraits of members of the court.

32 The intention of the Duke – to establish a collection of casts after his accession in 1772 – had been facilitated by the acquisition of plaster casts from the collection of Houdon. Eleven casts based on works of other artists and on antique statues belonged to this group.

33 Following this acquisition of casts made by a renowned artist from abroad, further casts were commissioned directly in Rome by the Duke’s agent Reiffenstein, while others were bought from traveling Italian plaster molders. Around 1775, some plaster casts were purchased from the Ferrari brothers – Italian plaster cast dealers operating in Germany at this time who were known to have left “a reasonable amount of this kind of statues” in the castle of Friedenstein in Gotha.

34 However, a further important contribution to this collection was made by the local court artist Friedrich Wilhelm Doell in the 1770s during his stay in Rome at the behest of the Duke. He made or purchased copies after antique originals as well as plaster casts, among them central pieces like the Apollo Belvedere, Borghese Gladiator and Venus de Medici. 35 When the collection of casts was founded in 1779, Doell contributed several works. 36 In 1782 he returned to Gotha and became Director of the Academy. He apparently continued to produce further casts based on his own models and moulds and established a business connection with Rost in Leipzig. 37 Only later was the aforementioned ‘wholesaler’ Rost commissioned to provide additional works, for which Doell had no model to draw upon. These however were based on antique sculptures in Dresden and Berlin – works such as the Dresden Vestal Virgins (Herculaneum Women) or the Berlin Knöchelspielerin (Girl Playing Knucklebones). 38 Significantly, despite the wide range of sources on which the Gotha collection drew it was always assumed at the time that the casts were taken from the original statues in Italy.”

“Publishing a first catalogue in 1779, the art dealer Rost had already established a workshop for casts as early as 1778. 62 The collection of plaster casts seems to have grown, but there is no reference to the Ferrari brothers, although he must have contacted them about that time. The moulds must have been purchased between 1779 and 1782, in order to publish a new catalogue, of which, as far as I know, no copy has survived. Its existence, however, is proven indirectly by announcements. 63 Rost’s shop was situated prominently in a vault of the popular Auerbach Court, where he probably displayed a fair number of his casts to the public. Thus, compared to the traveling dealers, he had the advantage of a permanent salesroom.”

“Rost, not doubting the high quality of the Ferrari casts, informed the readers of his 1782 catalogue that he had made a contract with the Ferrari brothers entitling him to use their moulds. It can be assumed that Rost’s view of the Ferrari brother’s casts was generally shared at that time. Nevertheless, he decided to add a specific touch to the collection beyond the too well known and limited assortment of the Ferrari brothers. His attempt to order moulds and casts in Italy cannot be verified in detail, although in 1786 he had announced the possibility of acquiring the Flora Farnese by subscription, and as early as 1794 he offered the small scale copy of this sculpture made by Doell in Rome in 1774.” 64 (Friedrich Wilhelm Eugen Döll, sculptor, 1750, Veilsdorf bei Hildurghausen – 1816, Gotha, Thüringen –1816)

“A further moulding campaign became important at that time: in 1782, Rost had called for a sale by subscription, principally of newly made casts of the collection in Dresden, 65 one of the few collections from Rome that had been purchased in its entirety by a German court. The collection had been acquired for Dresden by the Saxon King August the Strong in 1773. It was never displayed adequately, since, due to lack of money, nothing became of extensive plans for a new museum of sculpture. 66 From the collection of Prince Eugen in Vienna the three Herculanean Vestal Virgins (Herculaneum Women) were added. With some delay, the Dresden Collection of Antiquities Rost’s casts of twenty-five selected pieces from this collection apparently earned positive feedback. His subsequent 1786 catalogue mentions the news of the moulding campaign in Dresden first; the standard repertoire from the Ferrari moulds and other unnamed sources, primarily from Italy, are listed only subsequently.”

68

“The Ferrari had had a monopoly position and an exclusive circle of customers, compared with the increasingly competitive environment among mercantile traders local to the region, although in the beginning there seems to have been little space beside Rost for other dealers. Some court artists made casts from their respective collections of statues and busts and sold them; few, like the aforementioned Doell, had the opportunity to draw on their own first-hand copies of antique originals. At the same time, however, he was dependent on the marketing of Rost, who was able to reach a wider circle of customers and only comparatively late, around 1795, was Doell able to establish his own profitable workshop. 69

Competition had developed principally in Weimar. Gottlieb Martin Klauer settled there in 1777. 70 On Goethe’s suggestion and by order of the Duchess Anna Amalia he traveled to Mannheim in 1777, to study the casts of ancient sculptures, since at that period knowledge of them was considered indispensable for the development of an artist’s taste. At the same time, after the Weimar Palace had burnt down in 1774, the question arose as to how the Residence should be redecorated. 71

By order of the Weimar court, Klauer was able to acquire plaster casts in Mannheim, that had been cast from the original moulds. One of these casts was the very popular

Fede Group, a group of Amor and Psyche at that time interpreted by restoration as Caunus and Biblis. Thereafter, the Ildefonso Group was acquired, interpreted as Castor and Pollux, as well as several casts of heads.” (Martin Gottlieb Klauer, sculptor, born August 29, 1742 in Rudolstadt , died April 4, 1801 in Weimar, court sculptor in Weimar (1773) and art teacher at the local Princely Free Drawing School 1781)

“The Lauchhammer cast iron copies of antique statues had been announced already in the first volume of the Journal des Luxus und der Moden. 82 Rost himself had invented a “compact material” ( Feste Masse) that was resistant to weather conditions. All these undertakings would have been unthinkable without Rost’s collection of moulds, particularly from the Dresden collection, 83 and initially he sold the iron castings as well as Toreutica on commission. Subsequently however, the manufacturers became independent: Klauer published his first catalogue in 1792 and presumably Lauchhammer might have published something similar. 84 At about this time, direct criticism of the quality of Rost’s plaster casts accumulated and was published in journals. Critics cast doubt on the origin of the moulds of the best originals, accusing them of poor quality. 85 It seems that the contrast between the casts taken from the Dresden originals and the older plaster casts was so noticeable that Rost discredited himself. By producing these direct casts, exact plaster casts were circulating for the first time, clearly revealing the strong variation in quality. In 1794 Rost finally abandoned the habit of listing antique statues from Dresden and elsewhere separately, and instead integrated them all into the same list. Even though he vehemently defended himself against criticism, both in journals as well as in the preface to the 1794 catalogue 86 he must have been aware of the problematic origin of the moulds made by the Ferrari. In the meantime, the famous collection of casts by the Saxon court painter Anton Raphael Mengs had been purchased for Dresden and made accessible to the public – at first provisionally in 1786 and eventually arranged in a representative manner in the Johanneum in 1794.

87 For the first time since the opening of the Mannheim Antikensaal

, these first-class casts of the best antique statues of Rome and Florence must have shown the high quality of antique sculptures to a large audience. Heyne’s judgment of Rost’s illustrated catalogue of 1794 shows in detail how much Rost had come under fire:

[…] the casts of Mr. R. may be esteemed highly however in one respect, this is with regard to those casts, that by the exceptional grace of the Elector of Saxony, he received permission to have moulded directly; and we assume these are the ones H. Rost accords the name of Original Moulds, for most of the other main pieces – such as Laocoön, Apollo, The Gladiator, etc., cast originally in Germany 20 years ago by the Ferrari Brothers, and these in turn having been cast hastily and hurriedly from the Farsetti collection in Venice with no permission by the owner, only through special favour of the custodian of the moulds – may not well be named Original Moulds. One may only compare H. R. casts to those of the former Mengs collection in Dresden to notice this difference […].

Charlotte Schreiter

Moulded on the Best Originals of Rome. Eighteenth-Century Production and Trade of Plaster Casts after Antique Sculpture in Germany

in: Eckart Marchand, Rune Frederiksen (Hrsg.), Plaster Casts: Making, collecting, and displaying from classical antiquity to the present, International Conference at Oxford University, 24-26 September 2007 (Berlin 2010), 121-142.

Excerpts from publication: Above

“Working in Rome, Winckelmann traced in the sculptures he knew there for the development of Greek style. Observing Roman copies of lost Greek works, he described the rise and fall of Greek art from its rigid, archaic origins, through the full blown beauty of the classical style which he associated with the sculptures of Praxiteles, to the decline of Greek taste in what he called the Macedonian (Hellenistic) period. He divided the Greek history of art into four periods that constitute his taxonomic division:

The straight and hard lines of the archaic period – the Older Style;

The grand and square sculptures of the 5th century BC – the high Style;

The sculptures with flowering beauty and idealized naturalism in the 4th century BC – the Beautiful Style;

Lastly he identified an era characterized by its imitative and decadent copying of nature – the Style of the Imitators.

This model for the study of Greek art had considerable influence and was to be adopted as standard by subsequent generations of Hellenists (Jenkins 2003: 173–174). In addition, most of Winckelmann’s identifications of the subjects of individual sculptures as well as their dating in his chronological model continue to be accepted”

{Winckelmann’s identification “the Style of the Imitators” as the fourth period of Greek sculpture gets more than a bit dicey since later extensive discoveries of sculpture as well as a further understanding of the early Greco-Roman as well as it’s heritage from late Hellenistic sculpture progressed considerably in the nineteenth century and twentieth century. The later Hellenistic and early Greco-Roman period include what is much of the most significant Greek surviving sculpture. The more advanced artists from the High Renaissance through the nineteenth century periods were influenced in larger part by the Hellenistic and early Greco-Roman sculpture and to a lesser degree the Classical. The differentiation between these periods started with Winkelmann but he is less informed once the sculpture concerns the period of and after Alexander the Great. This critique influenced a rather imitative surface style after “Greek Classical” without the underlying complexity in visual abstracted content. Winkelmann though cannot be fully blamed since he is another academic without any deeper understanding of the abstracted complex visual content language inherent in Greek sculpture. Winkelmann seems to be making an analysis from a more obvious surface response – though Winkelmann was greatly gifted beyond his peers. Academics seem to have enormous difficulty in reading these abstracted complex visual content language. Most artists past and present are largely or completely ignorant or perhaps more ignorant especially now than Winkelmann of the issues. The best of the European sculptors though were going beyond this stylistic simplification. – my commentary, PBP}

Gotha, Friedrich W. E. Döll, sculptor, Vielsdorf, Thuringia 1750–1816

Gotha, Friedrich W. E. Döll, sculptor, Vielsdorf, Thuringia 1750–1816 Gotha, Weimar, Jena, Classicism in 18th. and 19th. Century Sculpture

Gotha, Friedrich W. E. Döll, sculptor, Vielsdorf, Thuringia 1750–1816, Part Two

Gotha, Friedrich W. E. Döll, sculptor, Vielsdorf, Thuringia 1750–1816 Gotha, Weimar, Jena, Classicism in 18th. and 19th. Century Sculpture

FIGURE MODELLO SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in two parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Figure Sculpture each time for the duration. The figure will be studied in greater depth than in the maquette course. The first half of the course will cover bone structure alignments, masses and proportion. The second half will focus on the surface of masses and surface anatomy. Both halves of the course will cover geometric patterning of shapes, commensurate planes, and planar rhythms.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 4-hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 3-hour evening sessions.

FIGURE MODEL SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in four parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Figure Sculpture each time for the duration. The figure will be studied in greater depth than in the modello course. The first half of the course will cover bone structure alignments, the masses and proportion. The second half will focus on the particular surface of masses, in depth surface anatomy and personality of the structures of the model. Both halves of the course will cover geometric patterning of shapes, commensurate planes, and planar rhythms. The added time length will enable a more mature articulated sculpture.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for each quarter – Day – four hour each class.

or

$ 1200.00 for each quarter – Eve. – three hours each class.

_____________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________\

FIGURE RELIEF SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in two parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique, or Modern Sculpture Plaster Figure, or Anatomical Model will be utilized several class sessions, to more extended projects within the two parts 9 meeting each time frame. Students will study bone landmarks and major muscle groups while working to capture the action of the pose and characteristics of the model. Overall forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated relief sculpture, defining sculptural content, and sketch composition. This course will establish how to develop a relief sculpture from a shape orientation method, as opposed to copying shadows, and light, which is not a dependable factor in representing content.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

Or

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

Or

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

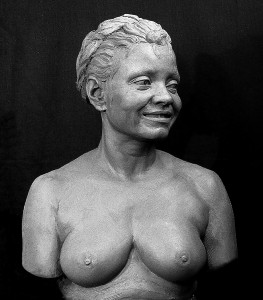

BEGINNING SCULPTURE PORTRAIT BUST COURSE

(detailed description)

This course consists of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique Sculpture Plaster Portrait Bust each time for the duration. Blocking in overall shapes, bone landmarks and major muscle groups, students will work towards capturing the likeness and character of the model. Overall, forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated portrait sketch.

Cost for the course:

$ 1120.00 for 9 – 4- hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

Frederich Wilhelm Eugen Doell, sculpture portrait bust of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Friedenstein Castle, Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Thüringen, Germany

_________________________________________________________________________________

PORTRAIT MODELLO SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in two parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique Sculpture Plaster Portrait Bust each time for the duration. The portrait will be studied in greater depth than in the maquette course. The first half of the course will cover bone structure alignments, masses and proportion. The second half will focus on the surface of masses and surface anatomy. Both halves of the course will cover geometric patterning of shapes, commensurate planes, and planar rhythms.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

________________________________________________________________________________

PORTRAIT SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in four parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three half hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique Sculpture Plaster Portrait Bust each time for the duration. The portrait will be studied in greater depth than in the modello course. The first half of the course will cover bone structure alignments, masses and proportion. The second half will focus on the particular surface of masses, in depth surface anatomy and personality of the structures of the model. Both halves of the course will cover geometric patterning of shapes, commensurate planes, and planar rhythms. The added time length will enable a more mature articulated portrait.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for each quarter – Day – four hours each class.

or

$ 1200.00 for each quarter – Eve. – three hours each class.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________

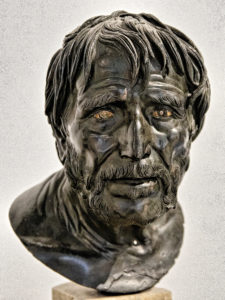

Pseudo Seneca Bust, Bronze, Napoli – Naples National Archaeology Museum, Greco-Roman copy of Hellenistic Bust, Herculaneum

Pseudo Seneca Bust, Bronze, Napoli – Naples National Archaeology Museum, Greco-Roman copy of Hellenistic Bust, Herculaneum

_____________________________________________________________________________________

PORTRAIT BUST RELIEF SCULPTURE COURSE

(detailed description)

This course will be taught in two parts, each part consisting of 9, four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique, or Modern Sculpture Plaster Portrait Bust, or Anatomical Model will be utilized several class sessions, to more extended projects within the two parts 9 meeting each time frame. Students will focus on bone landmarks and major muscle groups while working to capture the action of the pose and characteristics of the model. Overall forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated relief sculpture, defining sculptural content, and sketch composition. This course will establish how to develop a relief sculpture from a shape orientation method, as opposed to copying shadows, and light, which is not a dependable factor in representing content.

Portrait Relief of Clara and Husband Robert Schumann, – Doppelmedaillon von Ernst Rietschel, bildhauer, Dresden

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

Or

$ 1200.00 for first 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

Or

$ 1200.00 for second 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

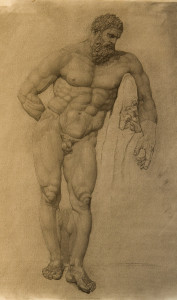

Farnese Hercules in the National Archeological Museum in Naples, Italy; version of the Hellenistic bronze statue by Lysippos, ca. 330 BC, signed by Glykon of Athens; charcoal drawing made on site by P. Brad Parker

_____________________________________________________________________________________

DRAWING COURSE – FIGURE & PORTRAIT MODEL / LIFE MODEL / ANTIQUE SCULPTURE / PLASTER CAST / ANATOMICAL MODELS / SKELETONS COURSE

(detailed description)

This course consists of 9 four-hour sessions (day), or three-hour sessions (evening). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Antique, or Modern Sculpture Plaster Figure / Portrait Bust, or Anatomical Model utilized each class session, to several class sessions through the 9 meetings. Students will focus on bone landmarks and major muscle groups while working to capture the action of the pose and characteristics of the model. Overall forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated drawing defining sculptural content, and sketch composition. This course will establish how to draw a person from a shape orientation method, as opposed to copying shadows, and light, which is not a dependable factor in representing content.

Cost for the course:

$ 1200.00 for 9 – 4 – hour daytime sessions.

or

$ 1200.00 for 9 – 3 – hour evening sessions.

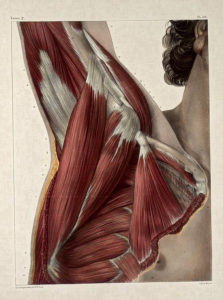

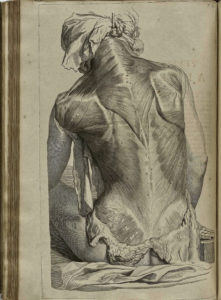

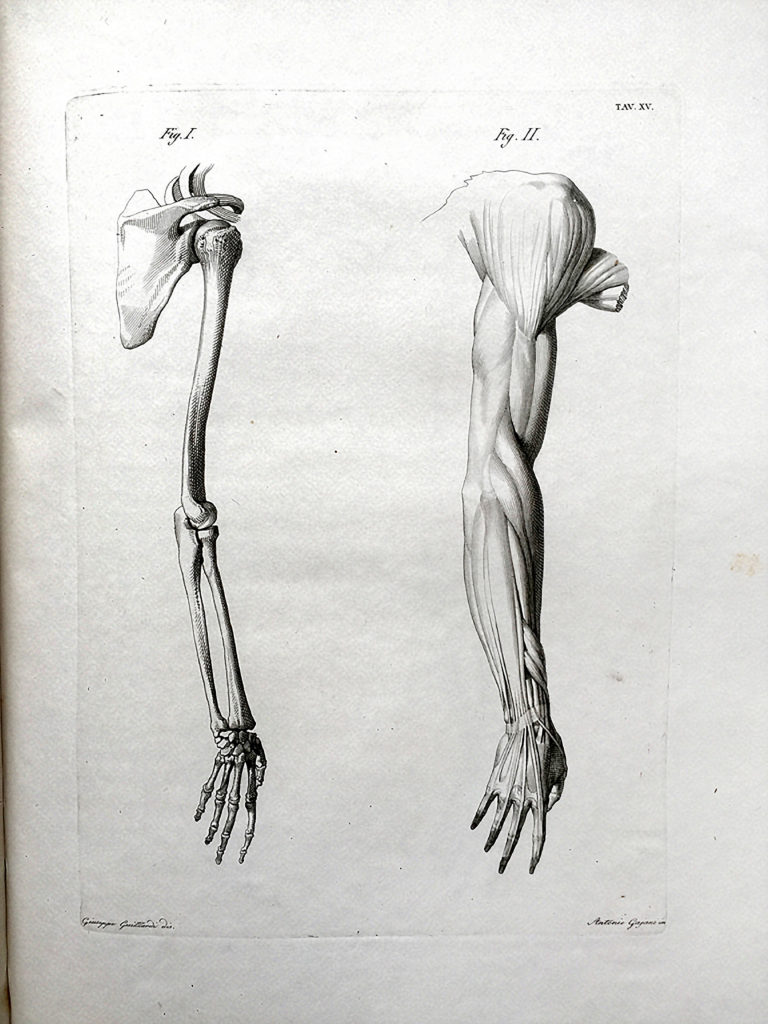

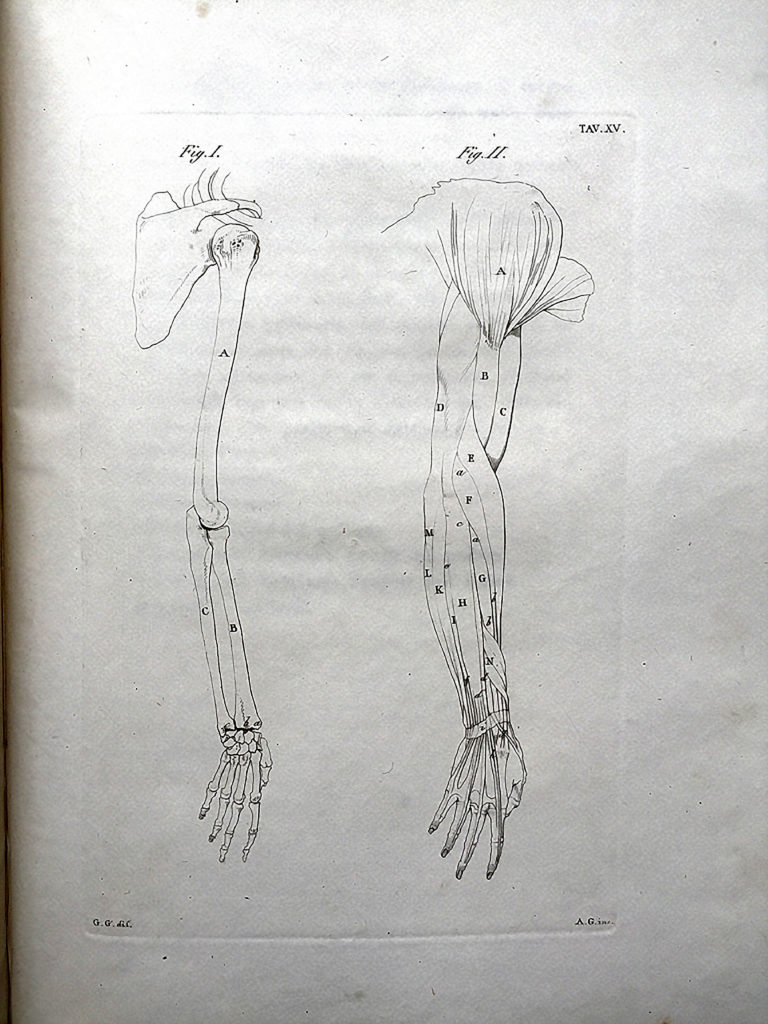

Students of painting and drawing, as well as those of sculpture, will benefit from these courses. Through the study of anatomy, running rhythms, natural geometric shape type, shape projection (seeing three-dimensionally from a single point of view), commensurate planes, balance, symmetry and asymmetry, the students will come to better understand the actual shapes of the bust or figure and to perceive the interrelationships which cause the figure or portrait to seem capable of function and movement. The instructor will point out specific shape types in the model and demonstrate how every large shape is reflected in each smaller part of the head or figure. Structural anatomy and the balance of weight and mass will be studied in depth. An understanding of the large masses as a base for smaller details will be strongly emphasized and, subsequently, the bust or figure will seem more natural and clearly ordered. Shadows will be used as a tool to reveal shape instead of hiding it. As a result of the course, students will become less likely to do work which appears oversimplified, disjointed or appear cartoon-like. Individual styles may be achieved later by choice rather than by mistake.

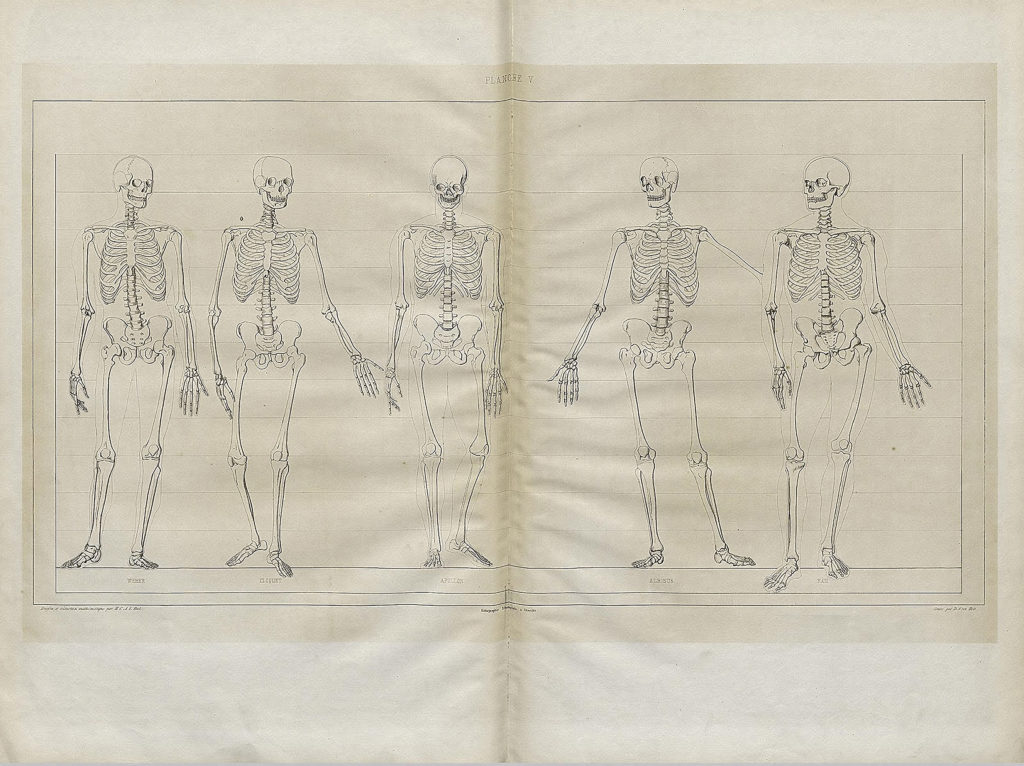

Students will also have visual access to a unique and extensive collection of anatomical models, anatomical figures and complete male and female European Skeletons. Sculpture Armature will be built in a class previous to the first weeks class with the model. A complete supply list is available for the Sculpture Armature and Sculpture Tools for enrolled students. Classes are limited to 10 students.

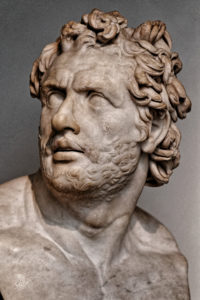

Polyphemus Group – Companion of Odysseus bust – British Museum, discovered 1860 in Tivoli, a gift by Caesar Tiberius to one of his Generals, re-sculpted as an additional bust from one of the Polyphemus figures

__________________________________________________________________________________

Polyphemus Group – Companion of Odysseus bust – British Museum, discovered 1860 in Tivoli, a gift by Caesar Tiberius to one of his Generals, re-sculpted as an additional bust from one of the Polyphemus figures

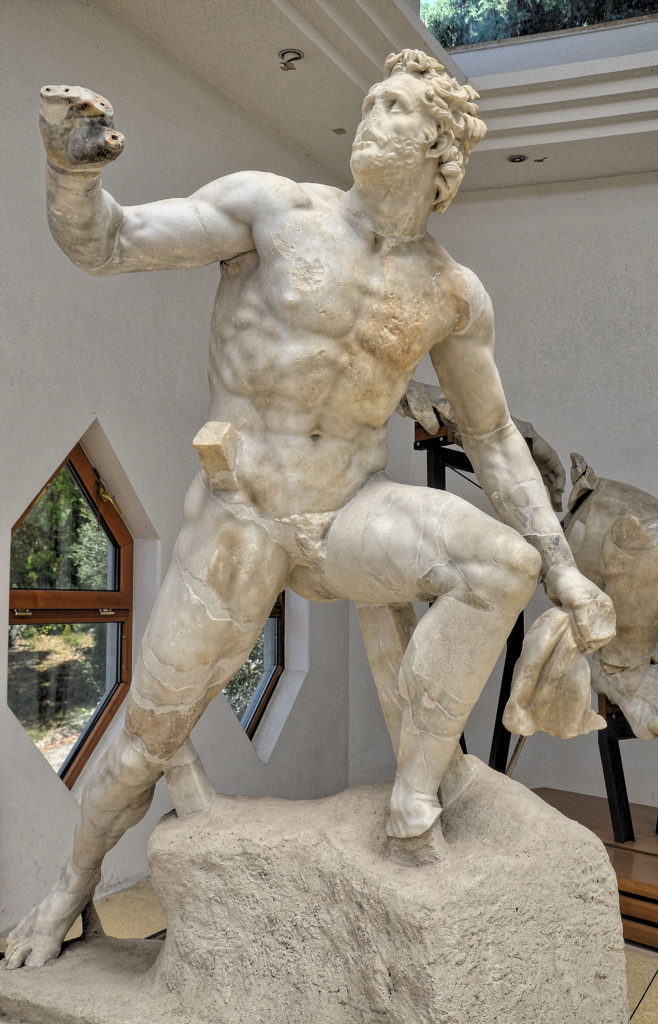

Sperlonga Museum, Polyphemus Group, Blinding of Polyphemus the cyclops (one-eyed giant) by Odysseus and his men, Cyclops Foot, Greco-Roman copy of an Hellenistic sculpture. Excavated in Sperlonga nearby grotto – villa of the Emperor Tiberius, the Rhodian sculptors: “Athenodoros, son of Agesander”, “Agesandros, son of Paionios” (Paionios is a rare name) and “Polydoros, son of Polydoros” signed on the sculpture base of this and one of the other groups found the “Scylla group”.

Sperlonga Museum, Polyphemus Group, Blinding of Polyphemus the cyclops (one-eyed giant) by Odysseus and his men, Cyclops hand, Greco-Roman copy of an Hellenistic sculpture. Excavated in Sperlonga nearby grotto – villa of the Emperor Tiberius, the Rhodian sculptors: “Athenodoros, son of Agesander”, “Agesandros, son of Paionios” (Paionios is a rare name) and “Polydoros, son of Polydoros” signed on the sculpture base of this and one of the other groups found the “Scylla group”.

Sperlonga National Museum, Polyphemus Group, Blinding of Polyphemus the cyclops (one-eyed giant) by Odysseus and his men, Cyclops Leg / Hand, Side View. Greco-Roman copy of an Hellenistic sculpture. Excavated in Sperlonga nearby grotto – villa of Emperor Tiberius.

One of Ulysses’s companions, the wineskin bearer, from the Blinding of Polyphemus group, Tiberian age, Sperlonga, Lazio, Italy

Polyphemus Group – Original marble, Sperlonga Museum, Blinding of Polyphemus the cyclops (one-eyed giant) by Odysseus and his men, One of the Ulysses (Odysseus) Companion, Greco-Roman copy of an Hellenistic sculpture. Excavated in Sperlonga nearby grotto – villa of the Emperor Tiberius, the Rhodian sculptors: “Athenodoros, son of Agesander”, “Agesandros, son of Paionios” (Paionios is a rare name) and “Polydoros, son of Polydoros” signed on the sculpture base of this and one of the other groups found the “Scylla group”.

Polyphemus Group – Original marble, One of the Ulysses Companion, National Archaeology Museum of Sperlonga

The Blinding of Polyphemus, cast reconstruction of the group, Sperlonga. During the high points of European art training which enabled the best results in the artists sophistication utilizing a complex visual language in producing their mature artworks – understanding by intensive study and replication of abstract visual complexity orders after the highest quality plaster casts of Antique Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture as well as original Greek and Greco-Roman sculptures where available were the most important factor in that education. Anatomy referenced here is the simple language in art education which to have relevance to Greek and Greco-Roman must incorporate and interplay with complex visual geometric orders content to which the anatomical study and implementation are subordinate. The best surviving Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture is the hallmark of achievement in European art of which the Renaissance through our period today is secondary lesser art in comparison. Greek Classical, Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman higher tier sculptures “style” is completely intertwined – it is undifferentiated – the style and the complex geometric orders of visual content are organically the same. European sculpture from the Renaissance through the early nineteenth century is predominantly “style” with a varying amount of complex geometric orders of visual content, though always secondary to the superficial “style” – in comparison to Greek and Greco-Roman sculpture in it’s best examples. Anatomy as taught in the more sophisticated ateliers and academies from the Renaissance through the late eighteenth century framed complex geometric orders of visual content together with subordinate anatomy based on Greek Classical, Hellenistic, and Greco-Roman sculpture. These Greek and Greco-Roman sculptures being the source material comprising the aesthetic complex visual content glue that held together relevance through the various European periods of art training.

Gottfried Schadow – POLICLET ODER VON DEN MAASSEN DES MENSCHEN NACH GESCHLECHT UND ALTER 1834 c

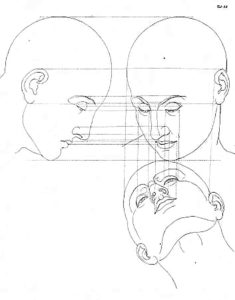

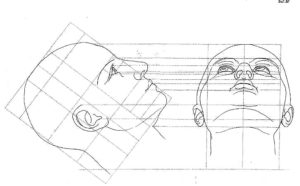

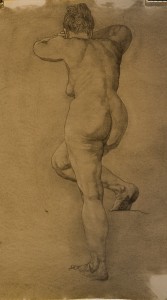

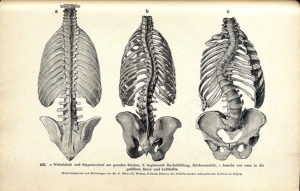

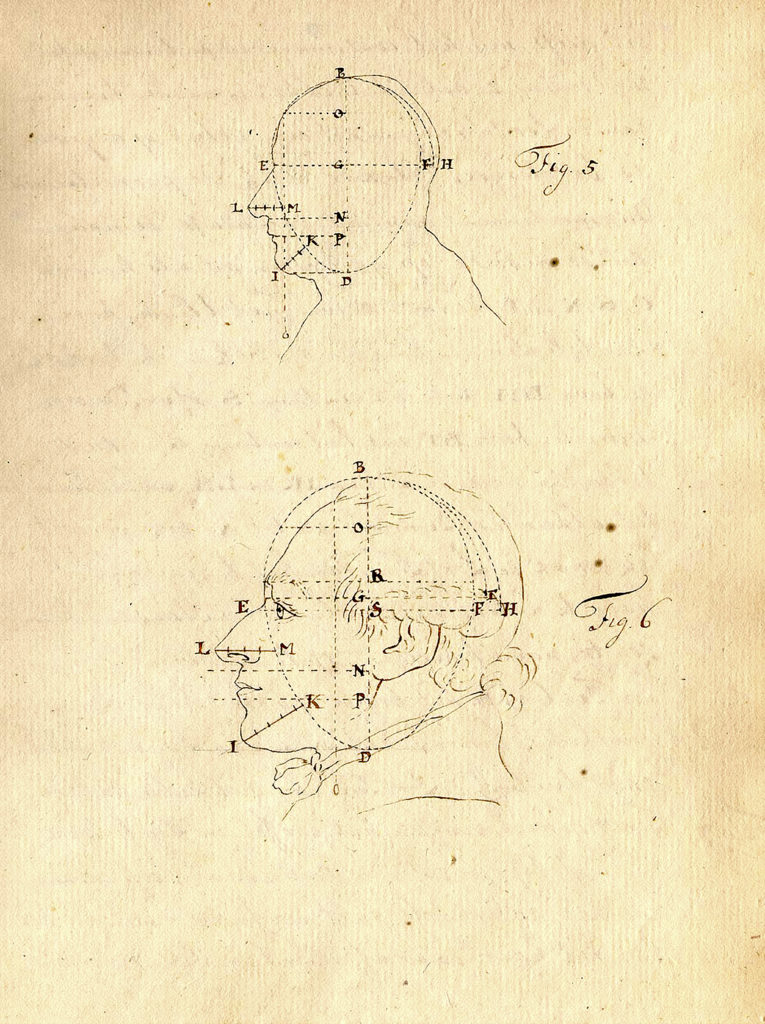

Johann Gottfried Schadow – Lehre von den Knochen und Muskeln von den Verhaeltnissen des Menschlichen Koerpers 2. These Johann Gottfried Schadow lesson drawings demonstrate foreshortening rules of proportion that proportions are interrelated and constant, remain true to the actual measured elements and not distorted contradicting interrelated scale as would be the case with perspective from angled viewpoints.

Johann Gottfried Schadow – Lehre von den Knochen und Muskeln von den Verhaeltnissen des Menschlichen Koerpers 2. These Johann Gottfried Schadow lesson drawings demonstrate foreshortening rules of proportion that proportions are interrelated and constant, remain true to the actual measured elements and not distorted contradicting interrelated scale as would be the case with perspective from angled viewpoints.