BEGINNING COMPOSITION FIGURE SCULPTURE COURSE

Marble Satyr and Hermaphrodite, Greco-Roman Imperial Period 1st century A.D., Villa A Oplontis, Excavation 1977 Pompei, Ercolano e Stabia

Contact: 301 633 2858, or 443 764 5364 by cell phone call, or text message, or contact: [email protected] to arrange a visit, or to enroll in a class or open group. Message Board below seems to have issues. Calendar is general information on classes available, days and times vary.

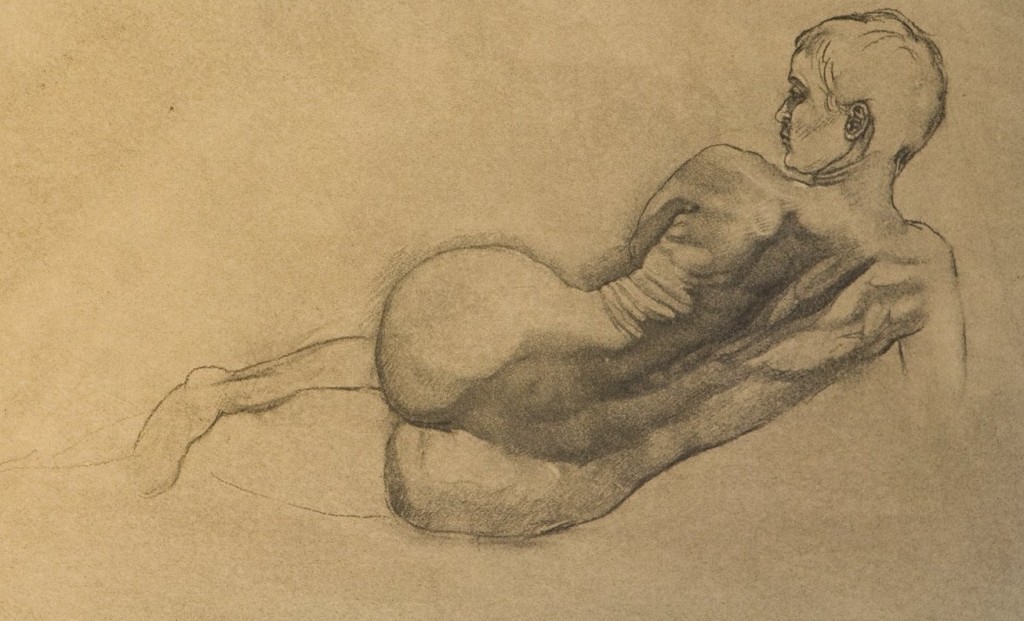

This course consists of 9 four-hour sessions (day time), or three-hour sessions (evening time). The same pose, and intended Life Model, or Figure Sculpture is each time for the duration of the course. There will be one half-hour to one-hour (day), or one half hour (night) review for the class after life model each session, making a total of four hours – (day), or three hours – (night). Additional optional limited workshop time is available without the life model, to work from a demonstration sculpture made during the class. Limited optional workshop time is coordinated as a specific time slot depending on the class, and availability during a particular week. Limited optional workshop time is included in the class price, but the workshop is not required for the class. Rescheduling the limited optional workshop is not possible after the timeslot is coordinated with the students for the semester. Students will focus on bone landmarks and major muscle groups while working to capture the action of the pose and characteristics of the model. Overall forms will be blocked in through observation of shapes, rhythms and interconnecting commensurate planes, leading to a simplified yet integrated sculpture sketch composition.

$ 1120.00 – ( 4 hour ) – // Day – x – 9

or

$ 1200.00 – ( 3 hour ) – Eve. – x – 9

[huge_it_gallery id=”11″]

The eye takes in information that the mind develops to realize subject and form. We only see what we think we know, and have learned to perceive. Through a series of exercises, students will begin the process of seeing dimensionally within a context of related shapes. Because of this study, students will initiate the necessary skills to construct aesthetic form. Sculpture study will comprise a three-dimensional figure sculpture in plasticine (non-drying clay).

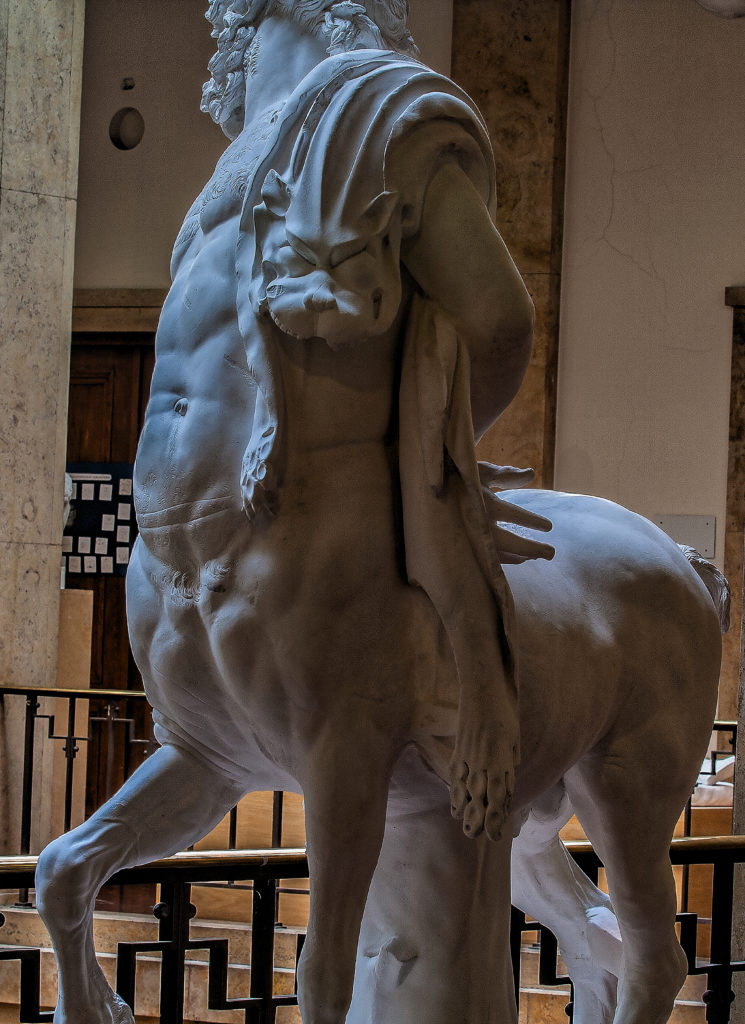

Galerie Antickeho Umeniv Hostinnem – Invitation to the Dance, plaster reconstruction of a Greco-Roman, Hellenistic sculpture group from various European museum collections of Greek sculpture, archaeologist Wilhelm Klein of Karlova University (Charles University) 19th. century reconstruction.

COURSE OBJECTIVES:

To develop perception of patterned shape

To develop the ability to take angles and proportions

To understand glyptek shape as it describes form

To develop turning rythems to create an effective composition

To develop visual scale from life to the sculpture

To understand commensurate planes

To learn basic anatomy

An armature appropriate to the above-mentioned class constructed prior to the first paid classes, as a free benefit for those that have paid for the 9-week session, is instructed and built in the Parker Studio Atelier. Each student supplies materials for the construction of the Figure Sculpture armature. Two cut to proper size, glued, and tacked together 22 x 22 inch A/C Exterior 3/4 plywood fir boards, (nail tacks should be counter sunk on the head side, and the point ends should not stick through the opposite plywood board surface). Next, the glue now dry between the tacked together plywood boards, the board should have three to five coats of polyurethane painted on all edges, also both front, and back main sides, which should be completely dry to the touch, and feel like the plywood is coated in thick plastic. After the completion of the preparation of the plywood boards, the board is brought to the free armature building class with plumbing pipe supplies, aluminum alloy sculpture wire rolls, flat head machine bolts, etc…, as detailed in the requested supply list. Additionally, Sculpture tools, and Chavant NSP Non-Sulfur, Soft Brown Plasteline are supplied by each student for their sculpture project, also detailed in the requested supply list.

___________________________________________________

Students of painting and drawing, as well as those of sculpture will benefit from these courses. Through the study of anatomy, running rhythms, natural geometric shape type, shape projection (seeing three-dimensionally from a single point of view), commensurate planes, balance, symmetry and asymmetry, the students will come to better understand the actual shapes of the bust or figure and to perceive the interrelationships which cause the figure or portrait to seem capable of function and movement. The instructor will point out specific shape types in the model and demonstrate how every large shape is reflected in each smaller part of the head or figure. Structural anatomy and the balance of weight and mass will be studied in depth. An understanding of the large masses as a base for smaller details will be strongly emphasized and, subsequently, the bust or figure will seem more natural and clearly ordered. Shadows will be used as a tool to reveal shape instead of hiding it. As a result of the course, students will become less likely to do work which appears oversimplified, disjointed or appear cartoon-like. Individual styles may be achieved later by choice rather than by mistake.

Students will also have visual access to a unique and extensive collection. There are Anatomical Models, and European Female, Male Skeletons available for reference, some of which were produced in Germany from the earlier 20th century: dissections cast from life into hand painted plaster – a series of four levels of the head / neck – from surface to deeper level structures, and a plaster hand painted anatomical torso; anatomical models of various scale, plasters from N.Y.C. full body in sections of dissection from life, as well as European Antique Sculpture Plaster Casts, and Anatomical scale Figure Plasters.

___________________________________________________________________________

Parking is free, there is plenty of space available for the model and students to park on the Square, as well as additional parking behind the townhouse in a private parking area.

___________________________________________________________________________

Mr. Parker is a graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where he studied for six years.

Mr. Parker studied concurrently at the Frudakis Academy of Fine Art at which time he received a National Sculpture Society Merit Scholarship. Later study in Europe in the first half of the 1990s.

Private Sculpture Studio, Drawing & Sculpture Classes, By Appointment – Open Drawing & Sculpture Group Sessions, Commissioned Portrait Bust Sculpture, Fountain Sculpture, Figure Sculpture, & Relief Sculpture Compositions. Private Gallery of exhibited sculpture, by appointment.

Farnese Bull Group – Napoli National Archaeology Museum – Greek Hellenistic Rhodian sculptors Apollonius of Tralles and his brother Tauriscus, end of the 2nd century BCE

Farnese Bull Group – Napoli National Archaeology Museum – Greek Hellenistic Rhodian sculptors Apollonius of Tralles and his brother Tauriscus, end of the 2nd century BCE

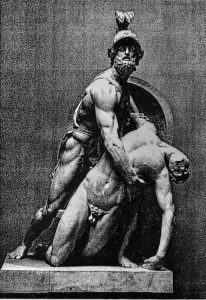

Blundell Collection, Liverpool, England – Satyr Raping Hermaphrodite, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman copy. The base was discovered with the group but does not belong to it. The inscription on the base is modern. The statue was found in the remains of a villa at Prato Bagnato on the Via Prenestina in 1776 by Nicola La Piccola and sold to Blundell in 1786. The statue of Dionysos (59.148.32) was found in the same context as well as the Head of Apollo and the Head of Isis. The base is a restoration and the inscription on the right end is modern. There are several restorations on the left arm and right leg of the hermaphrodite, her left breasts. Restorations to the satyr include the lower right leg from the knee, the lower calf and the foot, right thigh and some damage on the fingers and toes. The group may have been chemically treated and some recutting may have taken place in the hermaphrodite’s breast.

Silenus_and_infant_Dionysos_Vatican_MuseumSilenus holding infant Dionysos, copy Greco-Roman of the school of Lyssipos – Hellenistic original, – Vatican Museum, Braccio_Nuovo

Silenus holding Dionysos, copy Greco-Roman of the school of Lyssipos – Hellenistic original, – Louvre Museum

Silenus and the infant Dionysus by Lysippos, 370 – 300 B.C., Louvre Museum, Paris version, and Vatican Museum, Rome, version – Two Plasters Munich Cast Collection

Ares Ludovesi – Palazzo Altemps, Rome, Hellenistic, Greco Roman copy

Pasquino Group Menelaus with the body of Patroclus – Bernard Schweitzer reconstruction reference – Halle/Leipzig – Greco-Roman / Hellenistic sculpture in the Palazzo Pitti

Pasquino Group Menelaus with the body of Patroclus – Bernard Schweitzer reconstruction Halle/Leipzig – Greco-Roman/Hellenistic sculpture

Menelaus Carrying the Body of Patroclus (Ajax Carrying the Body of Achilles) ca. 200-150 BCE – reconstruction – Bernhard Schweitzer (archaeologist) 1936 – Halle/Leipzig

Menelaus and Patroclus, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman copy – Basel Antiken Plaster reconstruction by Ernst Berger, Skulpturhalle, Basel

Furietti Satyr the Elder from Aphrodesias – Hellenistic, Greco-Roman copy – Capitolini Museum, Rome – Plaster Munich

Furietti Satyr the Elder from Aphrodesias – Hellenistic, Greco-Roman copy – Capitolini Museum, Rome – Plaster Munich

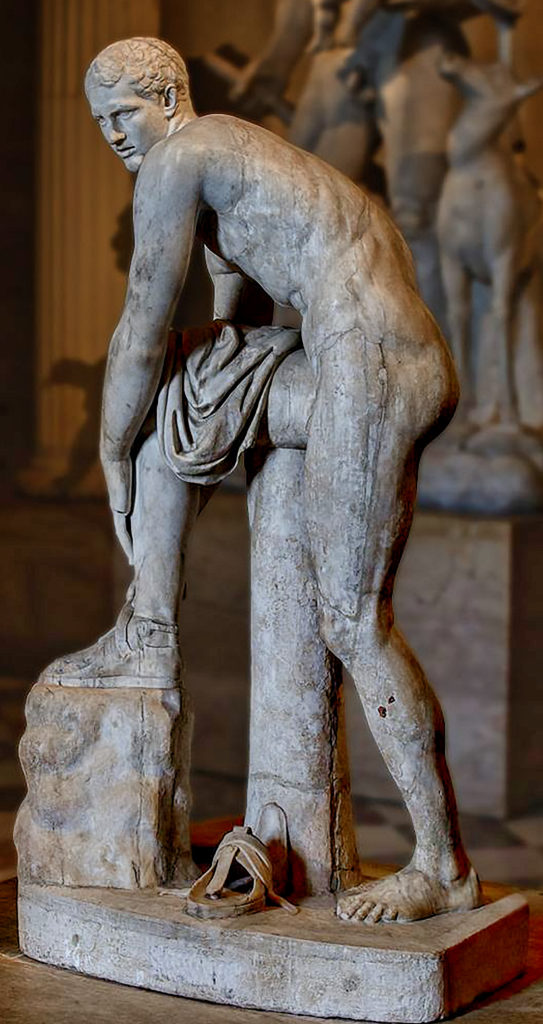

Jason the Sandal-binder, Cincinnatus, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman sculpture, Louvre – reconstruction with correct head in the Copenhagen Royal Cast Collection, this version in the Louvre has the wrong head

Jason the Sandal-binder, Cincinnatus, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman sculpture, Louvre – reconstruction with correct head in the Copenhagen Royal Cast Collection, this version in the Louvre has the wrong head

Jason the Sandal-binder, Cincinnatus, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman sculpture, Louvre – reconstruction with correct head in the Copenhagen Royal Cast Collection, this version in the Louvre has the wrong head

Jason the Sandal-binder, Cincinnatus, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman sculpture, Louvre – reconstruction with correct head in the Copenhagen Royal Cast Collection, this version in the Louvre has the wrong head

Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1521, Original: S. Maria sopra Minerva, Rome,

Der auferstandene Christus, Christ Risen, Plaster, Lindenau-Museum, Altenberg, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Germany, seitlich

Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1521, Original: S. Maria sopra Minerva, Rome,

Der auferstandene Christus, Christ Risen, Plaster, Lindenau-Museum, Altenberg, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Germany, seitlich

Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1521, Original: S. Maria sopra Minerva, Rome,

Der auferstandene Christus, Christ Risen, Plaster, Lindenau-Museum, Altenberg, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Germany, seitlich

Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1521, Original: S. Maria sopra Minerva, Rome,

Der auferstandene Christus, Christ Risen, Plaster, Lindenau-Museum, Altenberg, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Germany, seitlich

After a model by Giambologna, Netherlandish, Douai Florence, Rape of the Sabine Woman, cast probably 17th century, Bronze, marble pedestal, Height: 38 3/4 in. (98.4 cm);

Base: 14 in. ? 9 1/8 in. (35.6 ? 23.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

After a model by Giambologna, Netherlandish, Douai Florence, Rape of the Sabine Woman, cast probably 17th century, Bronze, marble pedestal, Height: 38 3/4 in. (98.4 cm);

Base: 14 in. ? 9 1/8 in. (35.6 ? 23.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

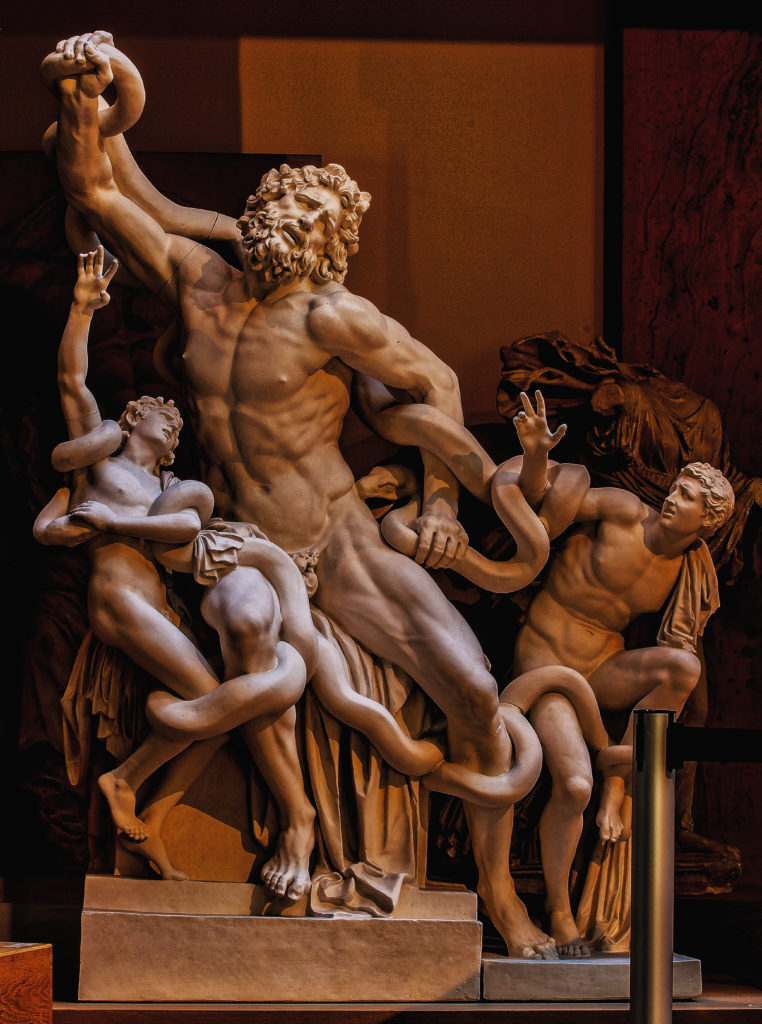

Adriaen de Vries, Laocoon

1600-25, gilded bronze, 58 x 39.5 x 23.2 cm, Statens Museum for Art / National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Art Copenhagen

Skulptur eines Farnesischen Stiers von Adriaen de Vries, Bronze, 1614, ausgestellt im Herzoglichen Museum Gotha (Thüringen), Germany

Christus an der Geißelsäule – Christ at the scourge column, – Adriaen de Vries, 1613, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria

Adriaen De Vries – Empire Triumphant over Avarice, Allégorie de l’Empire triomphant de l’Avarice, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Adriaen De Vries – Empire Triumphant over Avarice, Allégorie de l’Empire triomphant de l’Avarice, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Adriaen De Vries – Empire Triumphant over Avarice, Allégorie de l’Empire triomphant de l’Avarice, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Adriaen de Vries – Hilleröd Schloss, Frederiksborg Brunnen – Neptun´s fountain – Denmark, Triton Blowing a Conch Shell, c. 1615 c. 1618

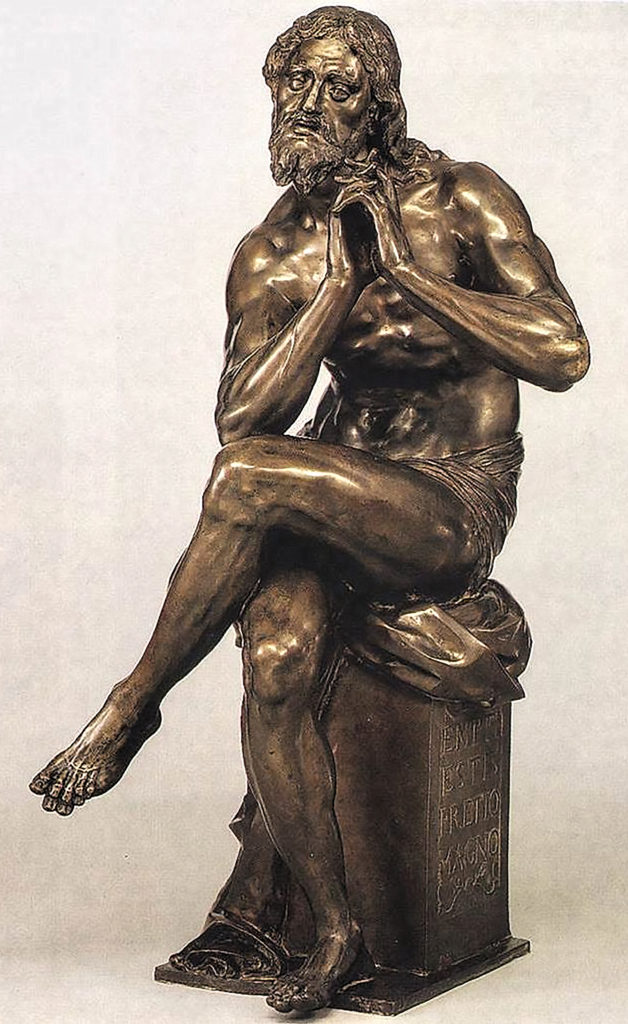

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

Adriaen de Vries – født Før 1546 død 1626, Lazarus 1615, Bronze, Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark

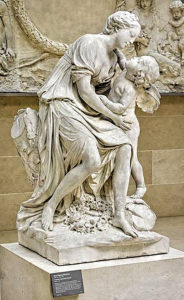

Madame de Pompadour 1721 – 1764 as Friendship in L’Amour embrassant l’Amitie sculpture, started in 1754 and completed in 1758 by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle 1714 – 1785

Madame de Pompadour 1721 – 1764 as Friendship in L’Amour embrassant l’Amitie sculpture, started in 1754 and completed in 1758 by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle 1714 – 1785

Madame de Pompadour 1721 – 1764 as Friendship in L’Amour embrassant l’Amitie sculpture, started in 1754 and completed in 1758 by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle 1714 – 1785

The Prinzessinnengruppe (Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and her sister Friederike) by Johann Gottfried Schadow, plaster, Friedrichswerder Church, Berlin, 1796 and 1797.

Prinzessinnengruppe Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and her sister Friederike Johann Gottfried Schadow – plaster, Friedrichswerder Church Berlin

Johann Gottfried Schadow Prinzessinnengruppe Prussian Crown Princess and later Queen Luise together with her younger sister Friederike 1795 1797 Alte National Gallery Berlin Museum

Johann Gottfried Schadow – Prinzessinnengruppe Preußische Kronprinzessin und spätere Königin Luise zusammen mit ihrer jüngeren Schwester Friederike, 1795 – 1797, Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin Museum

Christian Daniel Rauch – Kranzwerfende Viktoria, 1838–45, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Standort: Berliner Stadtschloss, Germany

Karl Friedrich Schinkel – Architect, Christian Daniel Rauch and Friedrich Tieck – sculptors, Schauspielhaus Ostgiebel Konzerthaus, concert hall Berlin, Tympanums above the main entrance Sculptures created by Christian Friedrich Tieck about 1820

Karl Friedrich Schinkel – Architect, Christian Daniel Rauch and Friedrich Tieck – sculptors, Schauspielhaus Ostgiebel Konzerthaus, concert hall Berlin, Tympanums above the main entrance Sculptures created by Christian Friedrich Tieck about 1820

Johannes Schilling, bildhauer – Vier Tageszeiten Abend (The evening) 1868, Statuengruppe am nördlichen Aufgang der Brühlschen Terrasse in Dresden, original sandstone restored 2017 in Chemnitz, Germany

Johannes Schilling, bildhauer – Vier Tageszeiten Abend (The evening) Statuengruppe am nördlichen Aufgang der Brühlschen Terrasse in Dresden, Bronze casts replaced the four original sandstone figures since 1908

Johannes Schilling, bildhauer – Vier Tageszeiten Abend (The evening) Statuengruppe am nördlichen Aufgang der Brühlschen Terrasse in Dresden, Bronze casts replaced the four original sandstone figures since 1908

Johannes Schilling, bildhauer – Vier Tageszeiten Abend (The evening) Statuengruppe am nördlichen Aufgang der Brühlschen Terrasse in Dresden, Bronze casts replaced the four original sandstone figures since 1908

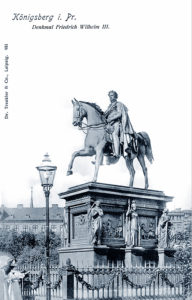

Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kiß, monument ceremony 3 August 1851 in the presence of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The ceremonial revelation of the monument took place on 3 August 1851 in the presence of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV and the Prussian prince Carl , Albrecht and Adalbert . The monument was considered the most representative of the city.

Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kiß, monument ceremony 3 August 1851 in the presence of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The ceremonial revelation of the monument took place on 3 August 1851 in the presence of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV and the Prussian prince Carl, Albrecht and Adalbert. The monument was considered the most representative of the city.

Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kiß, monument ceremony 3 August 1851 in the presence of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV

Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kaiser Frederick Wilhelm III. Denkmal Königsberg sculptor August Karl Eduard Kiß, monument ceremony 3 August 1851 in the presence of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV

Andreas Johnsen Kolberg – En drukken faun, Copenhagen, Denmark, A drukken faun, 1857. Gyldenløvesgade at St. Jørgens Sø (originally on Vestre Boulevard next to Tivoli)

Andreas Johnsen Kolberg – En drukken faun, A drukken faun, 1857. Gyldenløvesgade at St. Jørgens Sø (originally on Vestre Boulevard next to Tivoli)

Andreas Johnsen Kolberg – En drukken faun, Copenhagen, Denmark, A drukken faun, 1857. Gyldenløvesgade at St. Jørgens Sø (originally on Vestre Boulevard next to Tivoli)

Andreas Johnsen Kolberg – En drukken faun, Copenhagen, Denmark, A drukken faun, 1857. Gyldenløvesgade at St. Jørgens Sø (originally on Vestre Boulevard next to Tivoli)

Andreas Johnsen Kolberg – En drukken faun, Copenhagen, Denmark, A drukken faun, 1857. Gyldenløvesgade at St. Jørgens Sø (originally on Vestre Boulevard next to Tivoli)

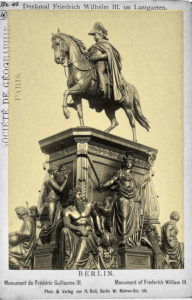

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III. im Lustgarten Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor Albert Wolff, after design of Christian Daniel Rauch – his main professor at the Berlin Academy of Fine Art.

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III. im Lustgarten Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor Albert Wolff, after Christian Daniel Rauch design

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III im Lustgarten, Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor, Albert Wolff. Spring 1869 the equestrian figure Friedrich Wilhelm III. was modeled, and was unveiled on June 16, 1871, the day of the return of the victorious troops from the Franco-Prussian War. Between autumn 1873 and 1875 Wolff created the base figures Klio, Borussia, religion, legislation, art and science. Except for the Rhine and Memel, which were produced in the Erzgießerei Munich, all bronze figures came from the art foundry Lauchhammer. They were unveiled on Sedan Day of 1876 (September 2). beyond monument Berlin Altes Museum und Lustgarten um 1900

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III im Lustgarten, Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor, Albert Wolff. Spring 1869 the equestrian figure Friedrich Wilhelm III. was modeled, and was unveiled on June 16, 1871, the day of the return of the victorious troops from the Franco-Prussian War. Between autumn 1873 and 1875 Wolff created the base figures Klio, Borussia, religion, legislation, art and science. Except for the Rhine and Memel, which were produced in the Erzgießerei Munich, all bronze figures came from the art foundry Lauchhammer. They were unveiled on Sedan Day of 1876 (September 2). beyond monument Berliner Dom

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III im Lustgarten, Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor, Albert Wolff. Spring 1869 the equestrian figure Friedrich Wilhelm III. was modeled, and was unveiled on June 16, 1871, the day of the return of the victorious troops from the Franco-Prussian War. Between autumn 1873 and 1875 Wolff created the base figures Klio, Borussia, religion, legislation, art and science. Except for the Rhine and Memel, which were produced in the Erzgießerei Munich, all bronze figures came from the art foundry Lauchhammer. They were unveiled on Sedan Day of 1876 (September 2). beyond monument Berliner Dom

Denkmal König Friedrich Wilhelm III im Lustgarten, Mitte, Berlin 1863, sculptor, Albert Wolff. Spring 1869 the equestrian figure Friedrich Wilhelm III. was modeled, and was unveiled on June 16, 1871, the day of the return of the victorious troops from the Franco-Prussian War. Between autumn 1873 and 1875 Wolff created the base figures Klio, Borussia, religion, legislation, art and science. Except for the Rhine and Memel, which were produced in the Erzgießerei Munich, all bronze figures came from the art foundry Lauchhammer. They were unveiled on Sedan Day of 1876 (September 2).

Rheinhold Begas – Pan als Lehrer Griesebach, Pan as a teacher of flute playing, 1858 / 68, Carrara marble, 70x67x40 cm, Begas Haus-Museum of Art and Regional History, Heinsberg, Germany, loaned by the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation

Rheinhold Begas – Trinkender Amor Kilger, The Watering Cupid, after models, 1867 – plaster, unmounted dm. 92 cm, Begas Haus Museum of Art and Regional History, Heinsberg, Germany

Rheinhold Begas – Amor Taube Kilger, Venus on the dove car, after models – 1867, plaster unmounted dm. 92 cm, Begas Haus-Museum of Art and Regional History, Heinsberg, Germany

Jakob Ungerer, sculptor – Municipal lapidary Stuttgart, inventory number 313 Tomb angel of an unknown grave, bronze 1893 Jakob Ungerer – model Prague cemetery

Jakob Ungerer, sculptor – Municipal lapidary Stuttgart, inventory number 313 Tomb angel of an unknown grave, bronze 1893 Jakob Ungerer – model Prague cemetery

Jakob Ungerer, sculptor – Municipal lapidary Stuttgart, inventory number 313 Tomb angel of an unknown grave, bronze 1893 Jakob Ungerer – model Prague cemetery

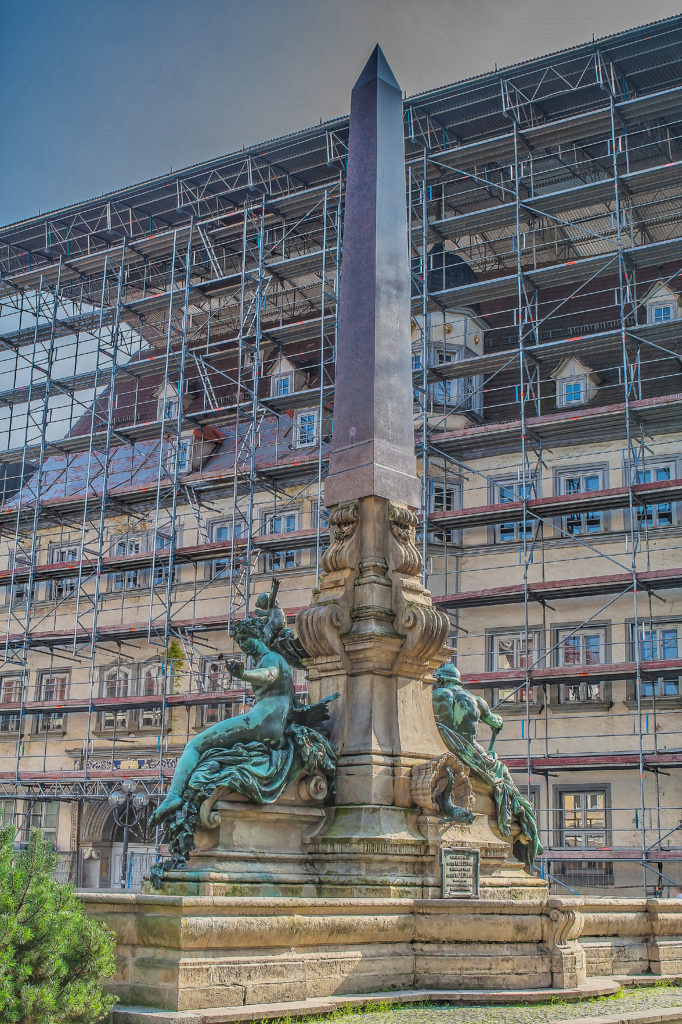

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Angerbrunnen – Kaiser Wilhelm I & II Denkmal, Erfurt, Thueringen, – bildhauer Professor Heinz Hofmeister, (1851 Saarlouis – 1894 Berlin), Architekt Friedrich Heinrich Stöckhardt, (born August 14, 1842 in St. Petersburg, † June 4, 1920 in Woltersdorf), the monument was inaugurated 1890

Denkmal des Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff – 1827-1871 Graz Tegetthoffplatz 1877 von Carl Kundmann 1838-1919 – sculptor

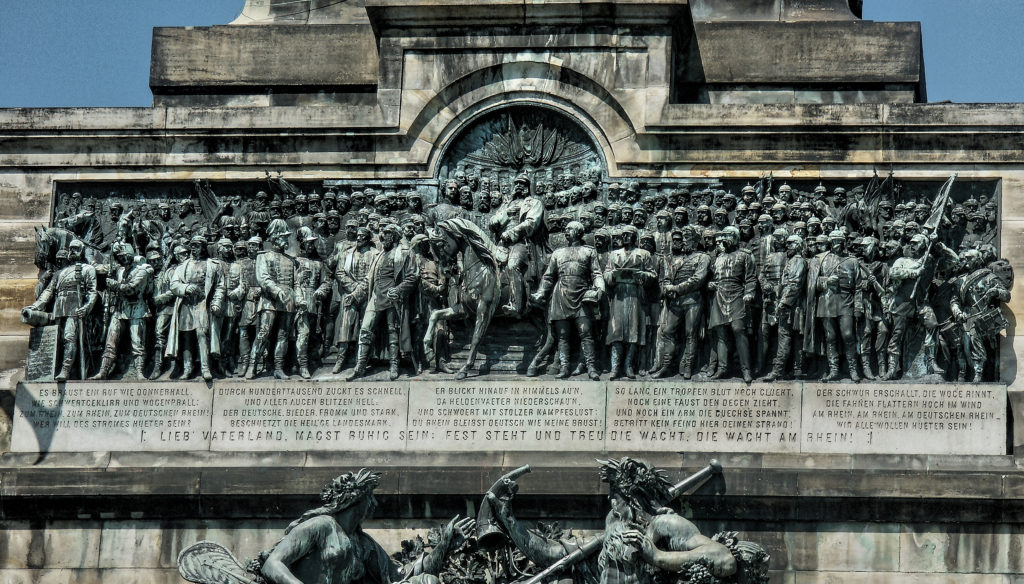

Niederwalddenkmal, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal – Germania, detail, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal – Germania, detail, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, detail – Germania frieden, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal – detail, Germania krieg, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Niederwalddenkmal, detail – Wacht Am Rhein, Rüdesheim am Rhein – Johannes Schilling, sculptor, architect was Karl Weißbach, the monument was inaugurated on 28 September 1883. The 38 metres (125 ft) tall monument represents the union of all Germans. The monument was constructed to commemorate the founding of the German Empire in 1871 after the end of the Franco-Prussian War.

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886. The portrait figure atop looks photo-derived but as a late period sculpture it’s better than most. Carl Kundmann being one of the better sculptors trying to maintain Classical/Hellenistic content within his figure sculpture at this late period – though with mixed results.

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886. The portrait figure atop looks photo-derived but as a late period sculpture it’s better than most. Carl Kundmann being one of the better sculptors trying to maintain Classical/Hellenistic content within his figure sculpture at this late period – though with mixed results.

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Praterstern in Vienna – Leopoldstadt, Tegetthoff Denkmal, Wein, Praterstern, Carl Kundmann, bildhauer – statue, and Carl von Hasenauer, architecture, unveiled on September 21, 1886

Equestrian statue Kaiser Wilhelm I at de Altonaer Rathaus Hamburg Altona, sculpted in 1898 by Gustav Eberlein

Equestrian statue Kaiser Wilhelm I at de Altonaer Rathaus Hamburg Altona, sculpted in 1898 by Gustav Eberlein

Erzherzog Johann Brunnen – The Archduke Johann Fountain at Hautplatz in Graz, – sculptor – Franz Pönninger ,

Erzherzog Johann Brunnen, The Archduke Johann Fountain at Hautplatz in Graz, Austria, sculptor – Franz Pönninger

Erzherzog Johann Brunnen – The Archduke Johann Fountain at Hautplatz in Graz, – sculptor – Franz Pönninger

Karl Janssen – Kaiser Wilhelm I Denkmal, in Düsseldorf Stadtmitte, von Osten, inaugurated on 18 October 1896

Karl Janssen – Kaiser Wilhelm I Denkmal, in Düsseldorf Stadtmitte, von Osten, inaugurated on 18 October 1896

Karl Janssen – Kaiser Wilhelm I Denkmal, in Düsseldorf Stadtmitte, von Osten, inaugurated on 18 October 1896

Karl Janssen – Kaiser Wilhelm I Denkmal, in Düsseldorf Stadtmitte, von Osten, inaugurated on 18 October 1896

Karl Janssen – Kaiser Wilhelm I Denkmal, in Düsseldorf Stadtmitte, von Osten, inaugurated on 18 October 1896

Johannes Pfuhl – Perseus befreit Andromeda, Posen heute im Wilson Park, in Posen Genregruppe Bronze, 1882 Zweitexemplar siehe 1896/8

Johannes Pfuhl – bildhauer, – Perseus befreit Andromeda – Posen heute im Wilson-Park in Posen Genregruppe Bronze 1882

[contact-form][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Telephone Number’ type=’text’/][contact-field label=’Name of the Art Class Course%26#x002c; or Open Group you are interested in attending%26#x002c; or requesting information on. ‘ type=’text’/][contact-field label=’City%26#x002c; State%26#x002c; Country’ type=’text’/][contact-field label=’The day of the week%26#x002c; the hours available%26#x002c; time frame you would be interested in an ongoing Class Course Session%26#x002c; or Open Group Session to participate in. There is the possibility of an additional Class%26#x002c; or Open Group Sessions depending on the response of enrollment%26#x002c; or participation interest. The main Art Classes page heading has what are active Class Course Sessions%26#x002c; and Open Groups. ‘ type=’text’/][contact-field label=’Potential Student%26#x002c; Artist participant in an Open Group%26#x002c; or you are a potential Life Model?’ type=’text’/][contact-field label=’New Field’ type=’text’/][/contact-form]

Comments

BEGINNING COMPOSITION FIGURE SCULPTURE COURSE — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>