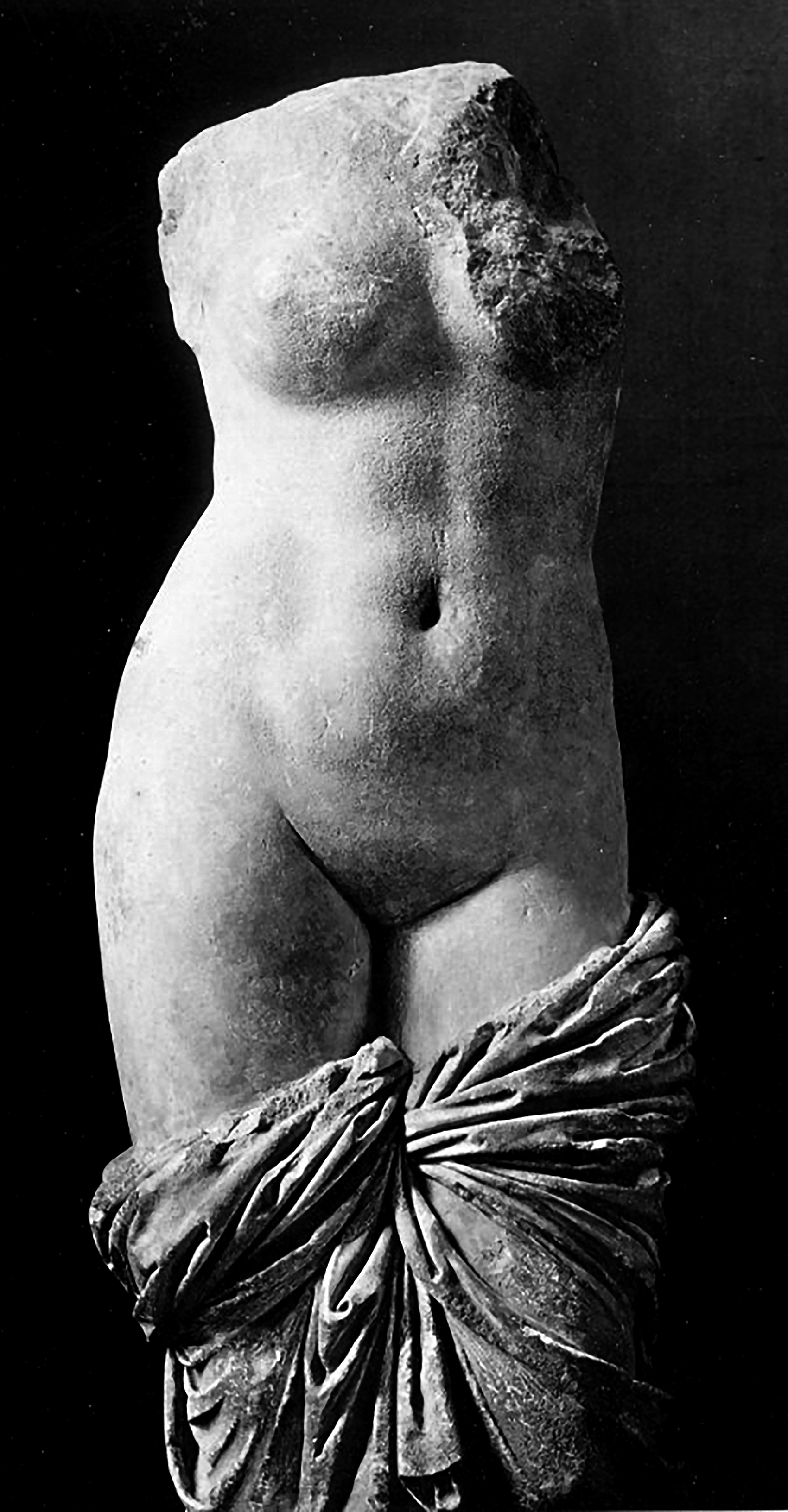

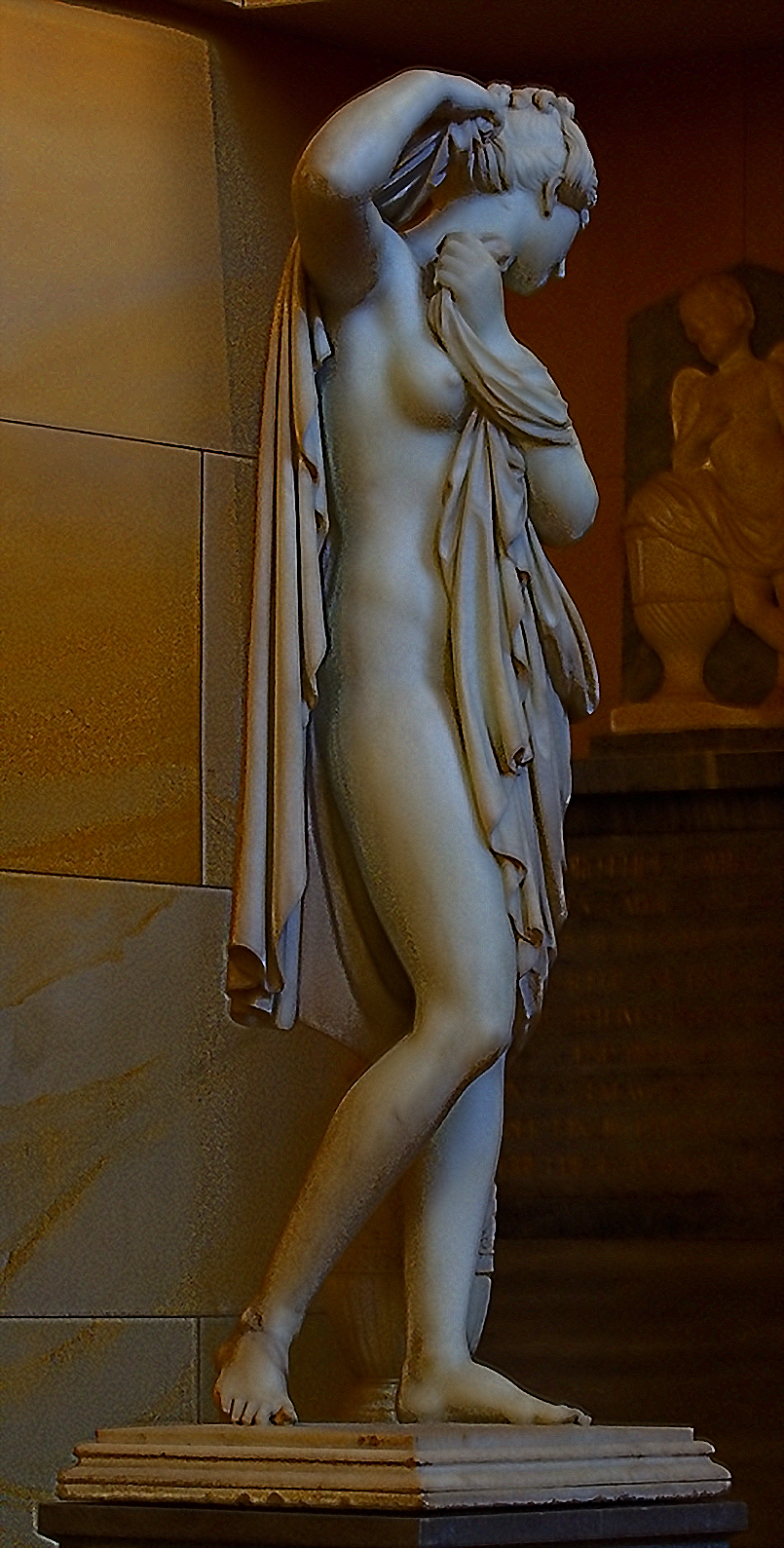

Aphrodite Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, related Female Hellenistic Sculpture

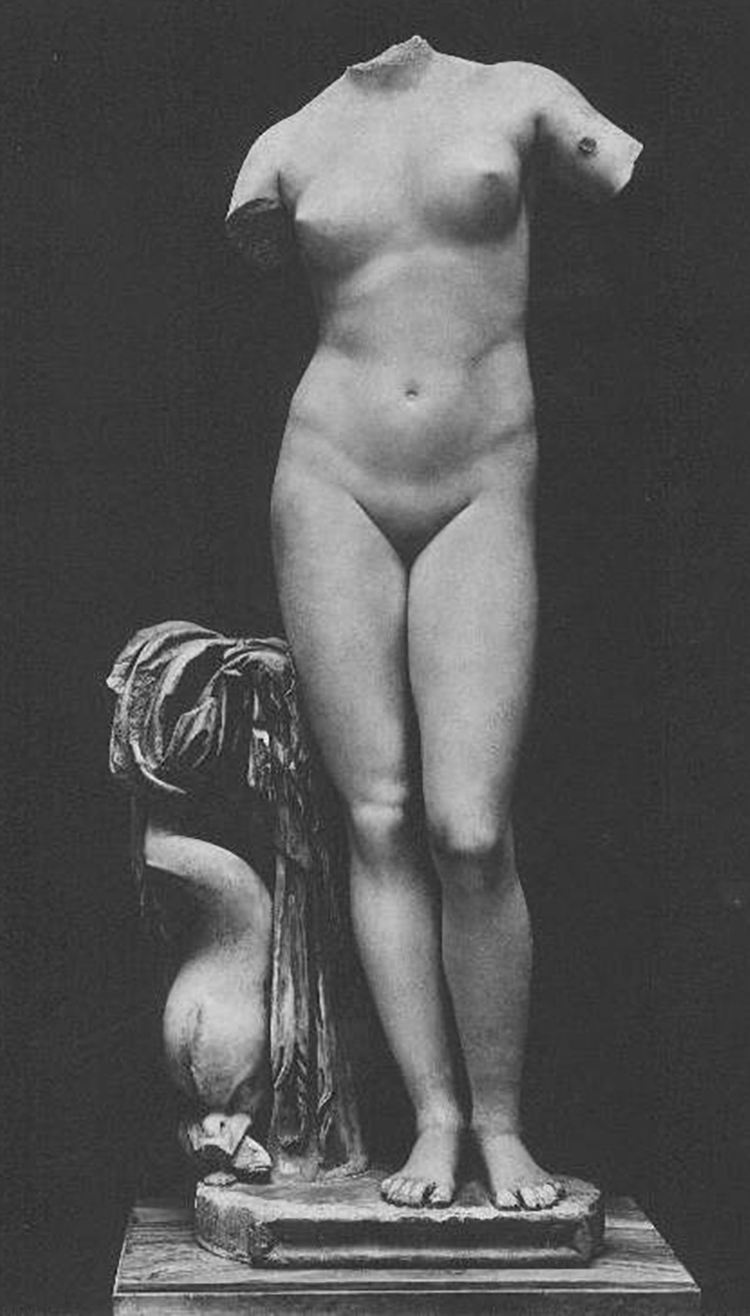

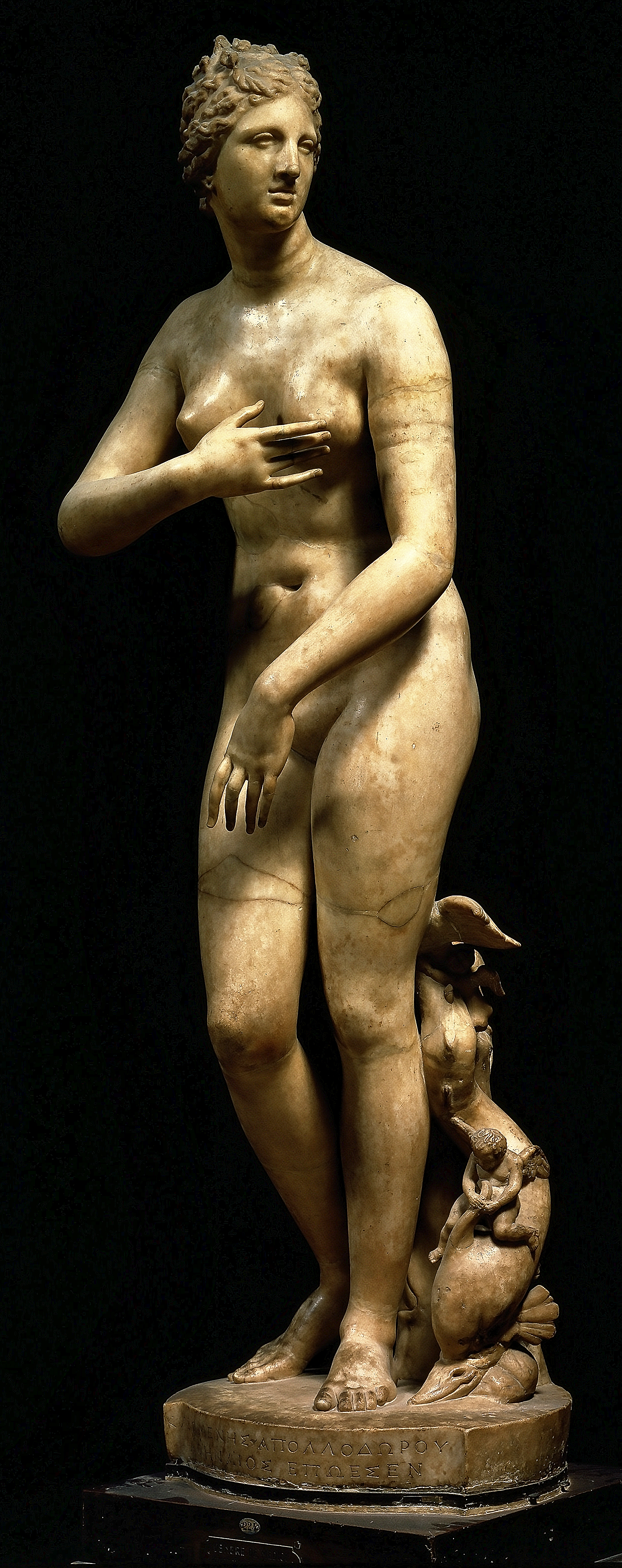

Venus de Medici, Uffizi, Florence, 10, Medicean Venus / Greek Sculpt./ C1st BC

Greek sculpture.

– So-called Medicean Venus. –

Sculpture, 1st century BC, by Cleome-

nes(?), after original by Praxiteles

from the 3rd century BC.

Marble.

Found 1680 in the Villa Hadriana in

Tivoli.

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

“The restorations of the arms was made by Ercole Ferrata, who gave them long tapering Mannerist fingers that did not begin to be recognized as out of keeping with the sculpture until the 19th century.

The marble Aphrodite at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,[11] is a close replica of the Venus de’ Medici.[12] The pose of the head is not in doubt, for it did not break off when other breaks occurred, in which the arms were irrevocably lost. On the plinth is the left foot, with part of the dolphin-and-tree-trunk support, and a trace of the missing right foot, restored by a cast, for the sculpture was in two sections, which were joined by casts taken of the Venus de’ Medici’s lower legs. For dating the replicas, attention is focused on the minor details of the dolphins that were added by the copyists, in which stylistic conventions come to the fore: the Metropolitan dates its Aphrodite of the Medici type to the Augustan period.

The Metropolitan Aphrodite was in the collection of Count von Harbuval genammt Chamaré in Silesia,[13] whose progenitor Count Schlabrendorf made the Grand Tour and corresponded with Johann Joachim Winckelmann.” Excerpts from Wikpedia

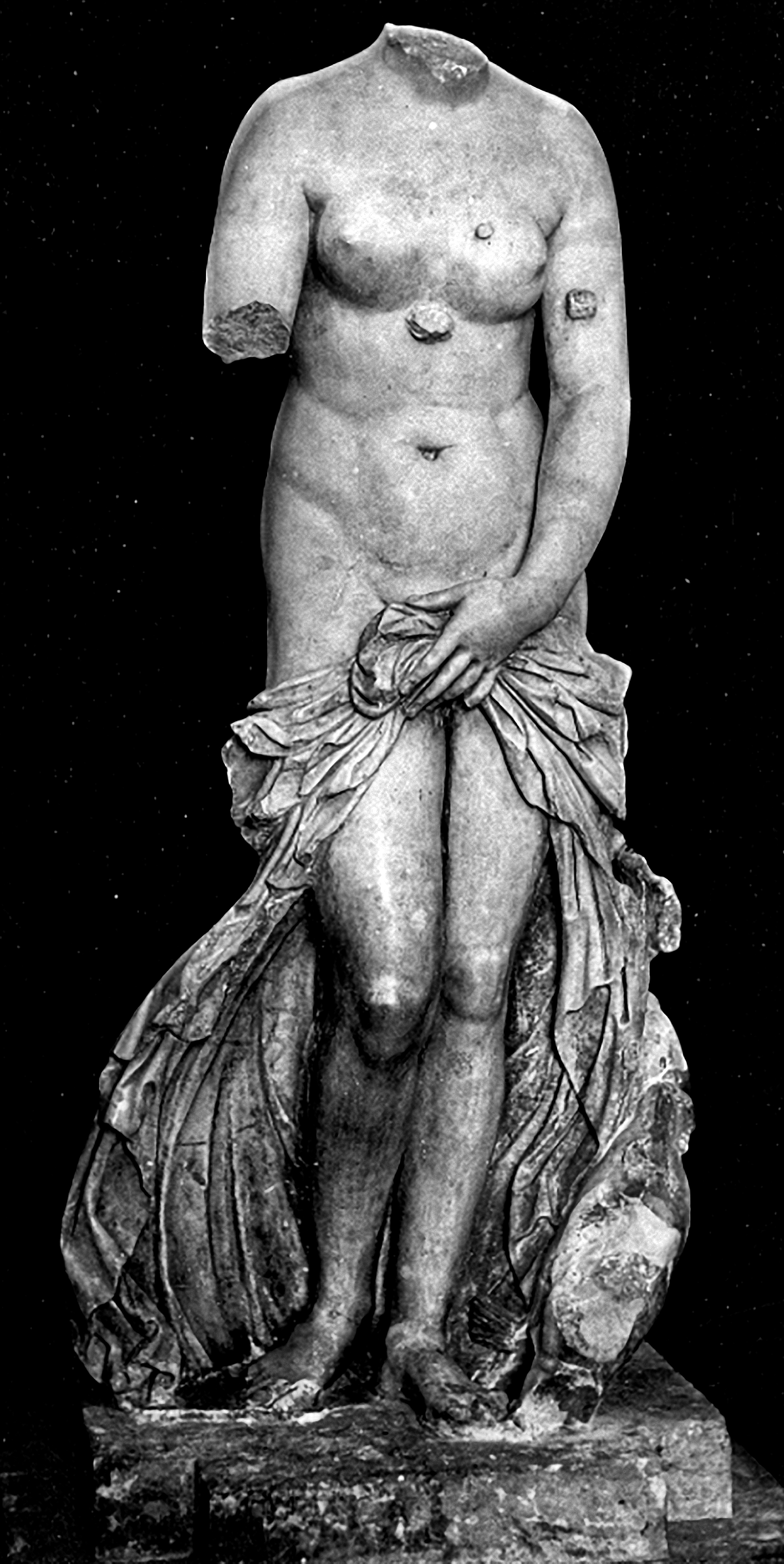

Aphrodite Hellenistic, Greco-Roman Sulptures, related Female Hellenistic Sculpture

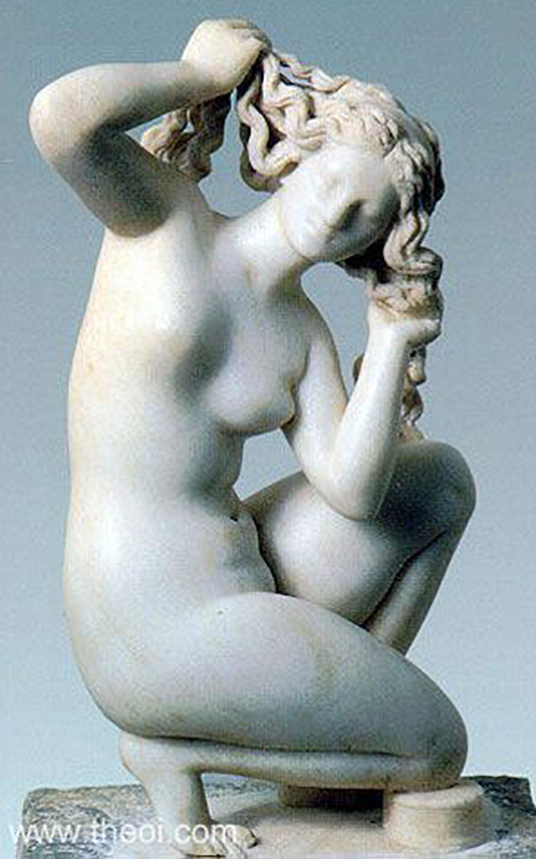

Kallipygos Aphrodite, Kallipygos is Greek for with a beautiful rump Greco-Roman marble copy after a Greek Hellenistic bronze, Naples National Archaeology Museum

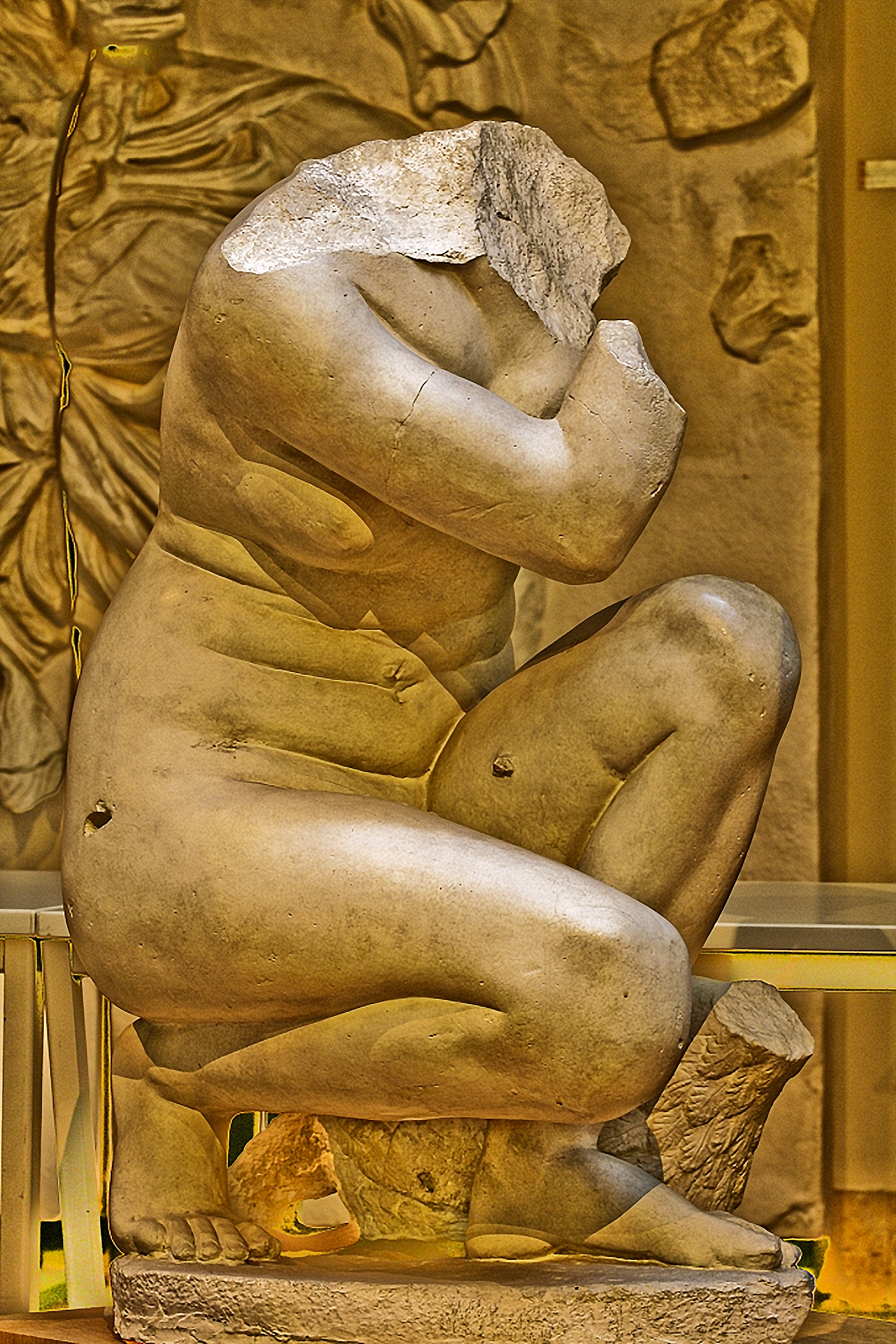

Crouching Venus loosely Derived from the Cnidian Aphrodite by Praxiteles from Sainte-Colombe Isère, France; Sully Room 17, Louvre, 1, A

Crouching Venus loosely derived from the Cnidian Aphrodite by Praxiteles From Tyre Lebanon; Sully Room 17, Louvre, 1, A

Aphrodite of Rhodes, Archaeological Museum Rhodes, Remodelling of Doidalos Type C.3 rd. B.C. to C. 1 st. A.D.; 1, A

Statue of a Woman, Woman in palla, a shawl with crown worn over head and shawl under tunic, Braccio Nuovo, Vatican, Rome, 1, A

Pudicizia, copia romana dell’età flavia (i sec. dc.) da originale ellenistico, con testa di reaturo Statue of a Woman, Braccio Nuovo, Vatican Woman in palla, a shawl with crown worn over head and under tunic, Rome, Italy

http://artgallery.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/coll_an_bull_2008_portrait_lady.pdf

Portrait of a Lady:

A New Statue at the Yale University Art Gallery

Lisa R. Brody

Both Greek and Roman societies judged men and women by certain standards. Women were expected to be modest, chaste, and reserved; these values determined her level of respect from family and peers.1 These personal moralities are central not only in the written traditions of the ancient world but also in its portraiture. Hellenistic and Roman portraits of women typically show them in canonical modes connected to certain traits, so that the images would be easily understood as commentary on lifestyle and disposition. The Gallery’s recent acquisition (fig. 1) is a perfect example of such a portrait; it follows a scheme known to scholars as pudicitia and asserts a strong visual statement about the decorous and modest character of the woman shown. She stands in a self-contained pose, her body enveloped by rich garments and one arm bent so that the hand is near the face. This type was a popular option for images of women, not only in freestanding statuary but also in relief sculpture, beginning in the eastern Mediterranean around the second century b.c. and spreading west.2 It continued to appear through the second century a.d., though with decreasing regularity after the early Imperial period. In creating a late Hellenistic or Roman portrait, artists chose from a variety of standard body types, most of which were loaded with meaning from centuries of dissemination. A woman might be shown as Aphrodite, even nude or semi-nude, and the image would be interpreted as a statement about the woman’s beauty and charm. Hellenistic examples frequently display less concern for individual appearance, so that even statues designed as portraits tend toward idealisation. In the Roman period, statues tended to be strongly personalised, often including a contemporary fashion hairstyle. Exceptions appear in the Greek East, where patrons and sculptors maintained strong ties to Hellenistic traditions. There are several variations of the pudicitia statue type, though all carry the same connotations when chosen for a portrait. Some versions shift the weight to the opposite leg and/or reverse the position of the arms. The arrangement and treatment of the drapery sometimes also varies. The new Yale statue is a high-quality example of the so-called Braccio Nuovo type, named for a statue in the Vatican Museums, in Rome (fig. 2). In this type, the edge of the mantle falls in front of the body, crossing over the left wrist and creating a long diagonal line that accentuates the figure’s elegant stance. The Gallery’s new statue was acquired at Sotheby’s in New York in December 2007.3 It came from a private owner in France and had stood in a garden there since being

Figure of a Woman, Roman 1 st. century B.C. early 1 st. century A.D. Marble, Yale University Art Gallery

Fig. 1 (opposite). Figure of a Woman, Roman,

1st century b.c.–early 1st century a.d. Marble, 7715⁄16 x 305⁄16 x 18¿ in. (198 x 77 x 46 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, Purchased with the Ruth Elizabeth White and Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., b.a. 1913, Funds, 2007.207.1

Fig. 2 above left, – Statue of a Woman, Braccio Nuovo Type, (right hand and head restored), Roman late 1st. century A.D. Marble, Vatican Museums. Fig. 3 above right Photoshop Reconstruction of fig. 1

Fig. 2 (above, left). Statue of a Woman, Braccio Nuovo type (right hand and head restored), Roman, late 1st century a.d. Marble, h. 6 ft. 9√ in. (2.08 m). Vatican Museums, Rome, Braccio Nuovo 23

Fig. 3 (above, right). Photoshop reconstruction of fig. 1

purchased from London antiquities dealer Robert Kime, who had acquired it at a Sotheby’s auction in England in 1987. Certain restorations, particularly the right arm, suggest that the statue was in a European collection by at least the nineteenth century, when such techniques were common.

The slightly over life-size marble statue, six feet tall, portrays a woman in a frontal pose with her weight primarily on her right leg, her left leg bent and set slightly forward. She wears a long dress (chiton) covered by a mantle (himation) and thin-soled shoes of soft leather. True to the pudicitia scheme, the left arm crosses in front of the torso, enveloped in layers of drapery. The original right arm would have been bent so that the hand was near the chin, possibly grasping the mantle that is drawn up over the head (fig. 3). The mantle is notable for its fringed edge, carefully and skillfully carved. Such fringe is a distinctive and individualising element; fringed garments were worn by both men and women in antiquity and were associated with Hellenistic royalty and the luxurious East.5 The closed shoes are another specific feature, a distinctive fashion element of metropolitan Rome.6 Since we lack the inscription that originally would have accompanied this statue on its base, we must rely upon such iconographic clues in discussing its identity and context.

The carving on the Gallery’s statue is exceptionally fine, showing great sensitivity to contrast in texture and detail of drapery. In typical Hellenistic-style sculptural fashion, the lines of the heavier chiton are visible beneath the thinner mantle overlay. The complex patterns of folds and creases balance the compositional lines and stabilise the figure. The face is idealised, the hair brushed back in waves from a central part. It recalls images of Greek goddesses and suggests a strong Classical tradition, such as existed in the Greek East even into the Roman era.7

Although largely complete, the statue has undergone several repairs and restorations. These treatments are now being studied to determine an appropriate plan for conservation and display. As mentioned above, the right arm is obviously restored. The marble limb may have been crafted in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, specifically for the restoration, or it may have been borrowed from another ancient statue. The long-sleeved garment on this arm suggests that, if ancient, it comes from a statue of a male barbarian. A round marble plug conceals the dowel used to attach the arm, and the seam where the arm joins the body was later filled with epoxy resin.

Other areas of the statue, including the chin and two fingers of the left and, were also restored in marble. There are significant repairs to the neck and surrounding drapery, with fragments of marble pieced together and the joins covered with epoxy resin. The nose, upper lip, and left pointer finger are restored using epoxy; some or all of these restorations were likely added by Robert Kime as the 1987 Sotheby’s catalogue seems to show the nose and part of the upper lip missing, with a dowel hole for a previous restored nose visible. There is a large chip missing from the proper right cheek, and another large loss on the back of the head (the latter was never repaired because the statue probably would have stood against a wall or in a niche, so that the back would not have been visible). Two holes in a broken area on top of the head indicate another restoration (now missing). The statue stands on a new marble base. The surface is covered with gray-black dirt and green moss as well as iron oxide stains, a condition that is a result of the statue standing outside. The 1987 Sotheby’s catalogue shows that it was already in a similar state then, suggesting that the object had already been in a collection and displayed outdoors for many years prior to 1987. Extensive cleaning and conservation will take place during the 2008–9 academic year.

After treatment, the pudicitia statue is certain to become a highlight of the Gallery’s collection. Surrounded by divine and mythological statues, portrait heads and busts, and other objects of ancient art, it will speak elegantly to the visitor of sculptural style and portrait traditions during

the late Hellenistic and early Roman eras. Scholars, faculty, and students will examine the significance of its type, costume, and probable context, while non-specialists will be drawn to the quality of its carving and the elegance of its composition. We at the Yale University Art Gallery look forward to seeing the statue through its course of conservation, from which we expect it to emerge as a spectacular example of ancient portraiture.

- The ancient Latin terms associated with these values include pudicitia, castitas, sanctitas, modestia, with related concepts such as eidos and sophrosyne in Greek. See R. R. Smith, Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 84–85; Paul Zanker, “The Hellenistic Grave Stelai from Smyrna,” Images and Ideologies: Self-Definition in the Hellenistic World, ed. Anthony Bulloch et al. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 222–27; Paul Zanker, “Brüche im Bürgerbild? Zur

bürgerlichen Selbstdarstellung in den hellenistischen Städten,” in Stadtbild und Bürgerbild im Hellenismus, ed. Michael Wörrle and Paul Zanker (Munich:

- H. Beck, 1995), 262–63.

- See, for example, the statue of Kleopatra from Delos in Smith, Hellenistic Sculpture, 84, fig. 113. On Hellenistic grave reliefs, see Ernst Pfuhl and Hans Möbius, Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs I–II (Mainz am Rhein, Ger.: Philipp von Zabern, 1977–79), 138–48, 413–51.

- Sale , Sotheby’s, New York, December 5, 2007, lot 69.

- Sale , Sotheby’s, Sussex, September 23–24, 1987, lot 598.

- When fringed cloaks are mentioned in ancient literature, the cloak is often purple or crimson and

the fringe gold, e.g. Ovid, Met. 2.734, 5.51. One instance of a very similar fringed mantle appears on the famous Hellenistic bronze dancer (the so-called Baker Dancer) owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York (inv. no. 1972.118.95). For such garments worn by men, with their connotation of luxury, see Christopher Hallett, The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 BC–AD 300 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 132–36.

- Norma Goldman, “Roman Footwear,” The World of Roman Costume, Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 116. Among the corpus of portrait statues from Aphrodisias, for example, only three of the twenty female statues whose footwear survives wear closed shoes; two of these also have contemporary metropolitan hairstyles. See R. R. R. Smith et al., Aphrodisias II: Roman Portrait Statuary from Aphro- disias (Mainz am Rhein, Ger.: Philipp von Zabern, 2007), 194.

- It is evident, despite the restorations to the neck and surrounding drapery, that the head does belong

to the statue. Making statues of a single block became particularly desirable in the early Roman period and later; see Smith et al., Aphrodisias II, 30.

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Painting of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi by Anton von Maron, ca. 1794.

The Sandalbinder, an antique statue restored by Cavaceppi, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (c. 1716 – December 9, 1799) was an Italian sculptor who worked in Rome, where he trained in the studio of the acclimatized Frenchman, Pierre-Étienne Monnot, and then in the workshop of Carlo Antonio Napolioni,[1] a restorer of sculptures for Cardinal Alessandro Albani, who was to become a major patron of Cavaceppi, and a purveyer of antiquities and copies on his own account.[2] The two sculptors shared a studio. Much of his work was in restoring antique Roman sculptures, making casts, copies, and fakes of antiques, fields in which he was pre-eminent and which brought him into contact with all the virtuosi: he was a close friend of and informant for Johann Joachim Winckelmann.[3] Winckelmann’s influence and Cardinal Albani’s own evolving taste may have contributed to Cavaceppi’s increased self-consciousness of the appropriateness of restorations[4] — a field in which earlier sculptors had improvised broadly — evinced in his introductory essay to his Raccolta d’antiche statue, busti, teste cognite ed altre sculture antiche restaurate da Cav.[5] Bartolomeo Cavaceppi scultore romano[6] (3 vols., Rome 1768-72). The baroque taste in ornate restorations of antiquities had favoured finely pumiced polished surfaces, coloured marbles and mixed media, and highly speculative restorations of sometimes incongruous fragments.[7] Only in the nineteenth century, would collectors begin for the first time to appreciate fragments of sculpture: a headless torso was not easily sold in eighteenth-century Rome.

In the competition for a permanent marble of Saint Norbert for the last available niche in St. Peter’s Basilica, Cavaceppi, the candidate favoured by Cardinal Albani, lost out in the end to the more conservative declamatory Baroque manner of Pietro Bracci, who received the commission.[8]

Cavaceppi, “now certainly one of the most underrated artist-personalities in that era” according to Seymour Howard, was the Pope’s chief restorer, and a measure of his other clientele may be drawn from the plates that illustrated the works of art that had been restored in his extensive studio in the Raccolta, which appeared in three folio volumes, 1768-72. Haskell and Penny note[9] that of sixty plates in the first volume, thirty-four reproduced works already belonging to Englishmen, while a further seventeen showed works in German collections. The remainder were divided among CardinalsAlessandro Albani and Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti (1684–1764) and Conte Giuseppe Fede,[10] with one more in the Capitoline Museum and another belonging to Jacques-Laure le Tonnelier de Breteuil, the Bailli de Breteuil.[11] The following year’s volume showed sixty plates of sculptures that were all on the market. Cavaceppi made a considerable fortune from his endeavors.

Cavaceppi’s studio, staffed with a host of assistants, was a stop for all the young connoisseurs making the Grand Tour. Goethe described his visit in Italienische Reise XXXII. Cavaceppi was entrusted with making casts of antiquities. Joseph Nollekens purchased from Cavaceppi the casts of the Furietti Centaurs that may still be seen at Shugborough Hall, Staffordshire; Cavaceppi also produced full-size copies in marble.

For his contributions in the formation of the Museo Clementino, based in large part on Albani’s collection, Cavaceppi was made a Knight of the Golden Spur in 1770[12] and was henceforth Cavaliere Cavaceppi. His sculptures were presented for sale in the Museo Cavaceppi between the Piazza di Spagna and the Piazza del Popolo, the part of Rome most frequented by foreigners.

In the 1770s he carved a reduced version of Trajan’s Column, which was purchased by the English virtuoso Henry Blundell to complement his antiqities at Ince Blundell; Blundell also acquired Cavaceppi’s working model, a wooden column painted in grisaille.[13]

At the time of his death, the collection of fragments and casts in the Museo was vast. Prince Giovanni Torlonia purchased over a thousand items from Cavaceppi’s legacy.[14] In some senses,Vincenzo Pacetti, who had collaborated with Cavaceppi on restorations and who supervised restorations and display of the Borghese collection at Villa Borghese was Cavaceppi’s successor.

An exhibition “Bartolomeo Cavaceppi”, curated by C.A. Picon in London, 1983, helped to bring him out of obscurity.

Some other sculptors in Rome renowned for their restorations

- Carlo Albacini

- Orfeo Boselli

- Ippolito Buzzi

- Ercole Ferrata

- Francesco Nocchieri

- Francesco Fontana

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi

- Vincenzo Pacetti

Notes

- His name was variously given in contemporary notices. Francesco Giuseppe Napoleoni, who provided sculptures for Bernini’s colonnade at St. Peter’s may have been kin, according to Seymour Howard, “Some Eighteenth-Century ‘Restored’ Boxers” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56 (1993, pp. 238-255) p 240 note 5.

- Tomasz Mickoki, “Zeichnungen und Stiche nach Skulpturen in polnische Sammlungen”, Jahrbuch des deutschen Archäologischen Institut, 1992:205; Mickoki is concerned with three antiquities that passed through Cavaceppi’s hands that are conserved in Poland, two sarcophagi and a grave stela.

- Winckelmann and Cavaceppi are discussed by I. Gesche, “Antikenergänzungen im 18. Jahrhundert: Johann Joachim Winckelmann und Bartolomeo Cavaceppi”, Antikensammlungen im 18. Jahrhundert, 1981:335ff.

- Quickly shifting parameters of what was considered appropriate in restoring antique sculpture is discussed in O. Rossi Pinelli, “Artisti, falsari o filologhi? Da Cavaceppi al Canova: il restauro della scultura tra arte e scienza”,Richerche di storia dell’arte 13/14 (1981:41ff.

- The designation Cav[aliere] shows that Cavaceppi, like Giovanni Battista Piranesi, had received the papal Order of the Golden Spur.

- “Collection of antique statues, busts, identified heads and other antique sculptures restored by Cav. Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, Roman sculptor””.

- Jennifer Montagu, Roman Baroque Sculpture: the Industry of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press) 1989.

- The details of the story, which “admirably documents the workings of power politics and intrigue in matters of taste, traditional factors in the competition for lucrative commissions in the art capital of Western Christendom” has been detailed by Seymour Howard, “Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’s Saint Norbert” The Art Bulletin 70.3 (September 1988), pp. 478-485.

- Haskell and Penny 1981:68.

- Conte Fede owned part of the site of Hadrian’s Villa where he carried out excavations in his property.

- Depasquale, “The Bailli de Breteuil, the Château de Breteuil and its literary connections” 2001.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was made a cavalier of the Golden Spur the same year. (Howard 1988:479).

- Haskell and Penny 1981:47

- Howard 1993:243 note 5.

References and Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bartolomeo Cavaceppi. |

- Bignamini, C. Hornsby, Digging And Dealing In Eighteenth-Century Rome(2010), p. 252-255

- G. Barberini and C. Gasparri, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, scultore romano (1717-1799)[exhibition catalogue, Museo del Palazzo di Venezia, Rome] (1991)

- Haskell, Francis and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900(1981. Yale University Press)

- Howard, Seymour, ‘Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’s Saint Norbert’, in The Art Bulletin; 70.3 (September 1988), pp. 478–485. [Howard appends a list of original sculptures by Cavaceppi.] S. Howard, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi Eighteenth-Century Restorer[Ph. D. thesis, New York] (1982)

Pudicitia – by the sculptor B. Cavaceppi, Italian sculptor, copia in marmo del xviii secolo della Pudicitia Capitolina del ii secolo d c copy

Carlo Albacini

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Amazon, marble after the original in the Capitoline Museums (Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Madrid)

Carlo Albacini (1739? — after 1807[1]) was an Italian sculptor and restorer of Ancient Roman sculpture.

He was a pupil of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, an eminent sculptor and restorer of Rome. Albacini was notable for his copies after classical originals such as the Farnese Hercules; his version of theCastor and Pollux at the Prado is now in the Hermitage Museum[2]) or the Capitoline Flora from Hadrian’s Villa,[3] for the Grand Tourist market. Like Cavaceppi, he also restored classical sculptures, notably the Farnese marbles, which Albacini worked on in 1786-89, in preparation for their transfer to Naples under the direction of the German painter Hackert and Domenico Venuti.[4] Some of his restorations were free, by modern standards: in the famous Farnese Aphrodite Kallipygos at Naples, the head, the exposed right breast, left arm and right leg below the knee are restorations by Albacini.[5] Not restored in Rome before shipment to Naples, however, were the Farnese paired Tyrannicides restored as Gladiators.[6] Albacini was the principal restorer for Thomas Jenkins, whose pre-eminent client was Charles Townley; Townley’s collection is at the British Museum. Townley introduced Albacini to Henry Blundell whose collection of Roman sculptures was magnificently displayed at Ince Blundell.[7] In 1776 Blundell, considering that a fine modern copy was superior to a mediocre antiquity, commissioned from Albacini a copy of a colossal marble head of Lucius Verus;[8] when the young Antonio Canova visited the workshops of Cavaceppi and of Albacini in 1779-80, he spoke to one of Albacini’s garzonieri who said he had already spent fourteen monthspointing up a copy of the Borghese bust of Lucius Verus and had five months of work still to do.[9]

The Farnese Aphrodite Kallipygos, (National Archaeological Museum, Naples) restored in 1780s

He catalogued the immense collection of antique sculpture, some of its freely restored, left by Cavaceppi,[10] and he assembled the collection of casts of Greco-Roman portrait busts that was sold by Filippo Albacini and can be seen in the Capitoline Museums, the Vatican Museums, in Naples, and at the Prado and Casa del Labrador, Aranjuez,[11] and especially at the National Gallery of Scotland, where the presence of a large group of plaster casts purchased from Albacini’s son in 1838 was the subject of a colloquium on the varying reputation and cultural significance of casts of classical sculptures and the varying parameters of ethical restorations.[12]

On a smaller scale his workshop, working with Luigi Valadier, produced the elaborate table-setting in gilded and patinated bronze and rare coloured marbles on the Romantic-Classical theme The Ruins of Paestum that was designed for Maria Carolina by Domenico Venuti, 1805.[13]

As marble masons, Albacini’s workshop also executed architectural sculptures, such as the two simple chimneypieces of white and coloured marble for the gallery ofFerdinand IV of Naples‘ hunting box, the Casino Reale at Carditello,[14] about 14 km northeast of Naples. Pedestals for sculpture, for which Albacini was to be paid, were shipped from Livorno in 1780 by Gavin Hamilton intended for Thomas Pitt, later Lord Camelford, who did not take them.[15]

His son, also Carlo Albacini (1777 – 1858), was a sculptor.

Some other sculptors in Rome renowned for their restorations

- Orfeo Boselli

- Bartolomeo Cavaceppi

- Ippolito Buzzi

- Ercole Ferrata

- Francesco Nocchieri

- Francesco Fontana

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi

- Vincenzo Pacetti

Notes

- Death as in Dizionario biographico degli italiani, (Rome 1960) vol. I:588

- Hermitage Castor and Pollux.

- A half-size copy is conserved in the Indianapolis Museum of Art; it was included in the exhibition The Splendor of Eighteenth-Century Rome, Philadelphia and Houston, 2000.

- Alvar González-Palacios, “The Furnishing of the King of Naples’s Hunting Lodge at Carditello”, The Burlington Magazine 146 1219, Art in Italy: Discoveries and Attributions (October 2004:683-690) pp 683.

- Gösta Säflund, Peter M. Fraser, tr. Aphrodite Kallipygos, Stockholm, 1963.

- Illustrated by Howard 1993 pl. 38c, as restored by Albacini, but see Andrew Stewart, “David’s ‘Oath of the Horatii’ and the Tyrannicides” The Burlington Magazine 143 1177 (April 2001: 212-219) p. 216 note 9.

- Gerard Vaughan, in Davies 1991.

- Jane Fejfer, The Ince Blundell Collection of Classical Sculpture 2: The Roman Male Portraits, 1997

- Hugh Honour, “Canova’s Studio Practice-I: The Early Years”, The Burlington Magazine 114 828 (March 1972:146-159) p.153, noting Canova’s Quaderni di viaggio.

- Seymour Howard, “Some Eighteenth-Century ‘Restored’ Boxer”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56(1993;238-255) p. 243.

- Seymour Howard, “Ancient busts and the Cavaceppi and Albacini casts”, Journal of the History of Collections 3(1991:199-217); Glenys Davies, “The Albacini Cast Collection – Character and significance”, Journal of the History of Collections 1991 32:145-165.

- Glenys Davies, ed. Plaster and Marble: the Classical and Neo-Classical Portrait Bust (the Edinburgh Albacini Colloquium), Journal of the History of Collections 3, (Oxford University Press) 1991.

- Alvar González-Palacios, Il gusto dei principi: arte del corto nel xvii e xviii secoli

- González-Palacios 2004:683, illus. p. 686 ; González-Palacios notes that the two chimneypieces in question were stolen from storage in 2002.

- Brendan Cassidy, “Gavin Hamilton, Thomas Pitt and Statues for Stowe” The Burlington Magazine 146 1221 (December 2004:806-814) p. 809.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carlo Albacini. |

Restoration of the sculpture Venus Kallipygos in the Naples National Archeological Museum, restoration on the Greco-Roman / Hellenistic original added by the sculptor Carlo Albacini (1739? — after 1807)

These sculptures below have some sophistication beyond the norm of European art from Carlo Albacini’s study after Greek sculpture and his restorations.

But his sculpture is more convincing as stylization than content from the Greek-influenced work he based his own sculpture.

AMAZON, at the Museum of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, in Madrid (Spain). Sculpted in white marble by Carlo Albacini (active between 1770 and 1807) around 1780. Dimensions: 71 x 26 x 23 cm. It’s a copy of the Greek original (440–430 BC) at the Capitoline Museums (Rome, Italy).

Statue of MINERVA, at the Museum of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, in Madrid (Spain). Sculpted in white marble by Carlo Albacini (active between 1770 and 1807).. Dimensions: 77 x 42 x 13 cm.

Statue of MINERVA, at the Museum of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, in Madrid (Spain). Sculpted in white marble by Carlo Albacini (active between 1770 and 1807).. Dimensions: 77 x 42 x 13 cm.

BACCHUS and ARIADNE, at the Museum of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, in Madrid (Spain). Marble sculpture by Carlo Albacini (active between 1770 and 1807).. Dimensions: 70 x 32 x 30 cm.

Franz Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm Wolf, – Bacchantin mit dem freilich hundezahmen Panther 1869, Friederichswerdersche Kirch Schinkel Museum, 1

Franz Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm Wolff (* 6. April1814 in Fehrbellin; † 30. Mai1887 in Berlin) –Bacchantin mit dem freilich hundezahmen Panther, 1869, FriederichswerderscheKirch, Schinkel Museum designed by Karl Frederich Schinkel – architect 1822 – 1823, Berlin, Germany

{This quite a step down from Greek Hellenistic sculpture quality, but it still shows even in the second half of the nineteenth century in the hold out regions for traditional Greek-influenced art that some issues were still understood. This is an example of the sculpture enclosed within a geometric shape (an alignment within and through a portion of a platonic solid), and elements of the combined mass of the female figure and the panther reflect the shape geometry of the forms of the female (Bacchantin). Part of this combined shape of the Bacchantin and panther start at the lateral proximal left external oblique (where the narrowing of the waist ends and the waist begins to proceeds out) of Bacchantin which proceeds in a horizontal arch across Bacchantin’s torso, over her right wrist / hand to the top head of the panther, down with and at the angle of the folds of drapery, across the vertical stump element, including the panther torso, hip, pre tail at tail base, to leg angled forward; the opposite side being the hip, and legs of Bacchantin through the ankle across to the lower forward fold of cloth at the center base, and including the front turning of the square base. This shape is also dimensional – the interior portion of this shape area: the panthers right olecranon (elbow) area, and Bacchantin’s left patella (knee) area, project forward together representing the same geometry as the glabella – between the superciliary prominence (forehead shape projection forward between eyebrows region). /// The same geometry of the whole shape of the panther & Bacchantin first described can be seen in the head of Bacchantin as seen at the narrow top of Bacchantin’s head just past the coronal suture / proximal parietal down both sides of the head to the lateral lower cheek bones, zygomatic and mass of the cheeks angled inward as proceeding distally / lower cheeks aligned with the lower nose, because of foreshortening the appearance of the shape ending at the lower lip / proximal mentalis (top chin). //// The proximal zyphoid around to both side of the projected 7th. intercostal out to the external mass of the rib cage and returning to the proximal (top) platform of the belly button transverse ligament, – reflect the same shape again, in the same right side up position as the panther Bacchantin shape element already mentioned.

All through this specific geometry is displayed. Because photography flattens shape, and only shows gradations of light, not geometric form, these examples are a bit difficult to see three dimensionally. Also, this is a very simplistic example of the order of shape geometry I have described, used as possible with the source picture.}, – , PBP

was a famous German animal sculptor 19. Century, towards. the animal Wolff.

After the training in the royal iron foundry in Berlin and with the royal institute for trade (to the forerunner DO Berlin) he extended his knowledge of the casting technology not least by the promotion Beuths with Soyer in Paris and in Munich with Johann Baptist Stiglmaier. Subsequently, it made itself independent in Berlin with its own bildgiesserei, which it handed to his brother over Albert later. He dedicated himself to the plastic representation of animals to a large extent.

It was represented since 1839 on the exhibitions of the Prussian academy of the arts and became 1865 member of the academy.

WORKS [WORK ON]

- Eagle relief for the eight bases of the lock bridgein Berlin center;

- ((The Sachsenrossbefore the Welfenschloss in Hanover.)) The Sachsenross is clear from sculptor Albert Wolff!!!

LITERATURE: [WORK ON]

- Bildwerke from three centuries in Hanover. Described of Gert of the east. Taken up by Hildegard Mueller. Hrsg. of the art association Hanover to its 125jährigen existence. Munich: Bruckmann 1957, P. 100-101 (Sachsenross before the University of Hanover).

Aphrodite, FriederichswerderscheKirch, Schinkel Museum designed by Karl Frederich Schinkel – architect 1822 – 1823

{This sculpture is influenced by the Venus Callypige, Napoli, Hellenistic sculpture pictured above & below. The German sculpture of Aphrodite here is not sophisticated in form-content, or as graceful as the Greek Venus Callypige sculpture.}, , PBP

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples can be considered one of the most important cultural centres in the world in terms of the quantity and quality of Greek and Roman relics it contains. The museum building was constructed in 1585, on the hill of Santa Teresa, then a solitary spot but now surrounded by the chaotic traffic of the city centre. The building was originally a Cavalry Barracks, built by order of Don Pedro Giron, Duke of Ossuna, viceroy of Naples; was later used as a University, and was finally turned into a museum under Charles of Bourbon.

The National Library was also situated here for a long period, up until 1922 when it was transferred to the Royal Palace. The initial nucleus of the museum was established by Charles of Bourbon to display the Farnese collection which he inherited from his mother. However, the subsequent enlargement of the immense artistic patrimony, determined by the addition of remains found in the archaeological excavations at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabia, led to the search for new premises, and the transfer to the present building. It is practically impossible to mention everyone of the enormous number of relics and works on display here, which makes the National Archaeological Museum of Naples one of the most authoritative and prestigious collections in the world; we will instead limit ourselves to some of the most important artistic works.

It should also be remembered that a change in exhibiting criteria has led, in the last few years, to a new arrangement of the areas open to the public.

Most notable among the various exhibits and rooms are the Farnese Hercules, from the Roman Baths of Caracalla; the Farnese Cup a splendid example of cameo, once a part of the Medici collections; the Halls of Villa Papyri, where numerous sculptural exhibits are displayed, brought here from the excavations at the Herculaneum villa; the Halls of the Temple of Isis, containing frescoes and other material from Pompeii, once kept in the museum’s store-rooms; the Doryphorus, an admirable copy from the original by Polyclitus, from Pompeii; the relief showing the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice; the “Tyrannicides”, Aristogeiton and Harmodius, the magnificent Roman copy of a Greek original of the 5th century BC; the Venus Callypige, from an Hellenistic original; the Farnese Bull, also from Capua; the small bronze of the Dancing Faun; the mosaic showing the Battle of Issus. Completing the vast array of exhibits are paintings from Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabia, sculptures, small bronzes, and a collection of vases. Among the latter, note the vases originating form Etruria, Attica, Lucania, Apulia and Campania. Among the exhibits linked to Etruscan culture, the Small Bronze of a Donor (5th-4th centuries BC) is of considerable importance; it was found in the Commune of Capoliveri (Island of Elba) at the end of the 16th century.

Aphrodite Kallipygos, National Museum Neapel

Der Name soll folgendem Vorfall seine Entstehung verdanken. Zwei sizilische Mädchen stritten sich, welche von ihnen am Hinterteil schöner sei. Ein Jüngling, zum Schiedsrichter aufgefordert, entschied für die ältere und vermählte sich mit ihr, sein Bruder mit der andern. Beide Mädchen, nun reich geworden, errichteten darauf der Aphrodite in Syrakus einen Tempel mit ihrem Bild in oben bezeichneter Stellung. Eine berühmte Statue dieser Art, wenn die Darstellung nicht etwa ein Hetärenmotiv ist, steht im Nationalmuseum zu Neapel.