A Genius in Draft Form By Catesby Leigh • January 20, 2018 9:00 AM, National Review

A Genius in Draft Form

By Catesby Leigh

•

January 20, 2018 9:00 AM, National Review

Tityus Drawing, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ca. 1530-32 (Lent by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017)

The Met’s superb exhibition of Michelangelo drawings illuminates the origins of the artist’s mastery.

On the façade of the church of Orsanmichele in Florence, more than a dozen niches contain faithful replicas of works by sculptors of the Quattrocento. One of the earlier ones is a statue of St. George by Donatello. A sculpture of the risen Christ, with St. Thomas extending his hand toward the wound in his side, was created by an artist born half a century after Donatello, Andrea del Verrocchio. Donatello’s St. George, shown gazing outward with his tall shield poised in front, is a handsome figure, but his static, frontal pose confines him to his niche. He is pictorially conceived, whereas Verrocchio’s two figures are dynamically, dimensionally designed, projecting boldly out of their niche into the viewer’s perceptual space. They are also a good deal more sophisticated in their modeling. They convey a more powerful sense of presence than Donatello’s figure. Which is to say they are more monumental.

It was Michelangelo, of course, who would take the monumental impulse the Italian Renaissance nurtured to heights only the best of the ancients attained. He did so as a sculptor, painter, architect, and — a landmark exhibition currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum in New York amply demonstrates — draftsman. The key to this achievement was his revolutionary insight into the formal means by which the Hellenistic sculptors of works such as the Belvedere Torso and the Laocoön, both of which he studied in Rome as a young man and both of which find echoes in much of his oeuvre, endowed the male nude with a riveting combination of structural articulation, coherence, and dimensional presence.

It was the incessant practice of drawing that enabled Michelangelo to internalize the concepts he absorbed from Greek sculpture, develop his mastery of form, and work out the designs in which that mastery found expression. Drawing was thus the foundation of masterworks including the decoration in fresco of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, completed in 1512; the Last Judgment fresco in the same chapel (1541); and the majestic sculptures in the New Sacristy (also known as the Medici Chapel) at San Lorenzo in Florence, on which the artist labored during the 1520s and ’30s. It was drawing, then, that largely accounted for the elderly Michelangelo’s being accorded the sobriquet Il divino, the divine one.

* * *

Michelangelo Buonarroti, by Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli), ca. 1544. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Clarence Dillon, 1977)

Born into an impecunious Tuscan family of the minor nobility, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) was generous to his friends, inexhaustibly industrious, proud, vain, subject to bouts of melancholy intertwined with a religiosity that deepened as he grew older, and, last but not least, capable of virulent animosity — most famously toward his younger rival, Raphael. Raphael would predecease Michelangelo by more than four decades. But while he was alive, he proved quite willing to take instruction from Michelangelo’s work, though Leonardo da Vinci was his main exemplar.

Michelangelo would have had his admirers believe that his brilliant feats were simply unheralded, breaking with Renaissance precedent rather than building on it. Verrocchio’s Orsanmichele sculpture shows us that’s not entirely true. But when we look at a celebrated engraving of ten nude warriors in action by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, a sculptor and painter roughly Verrocchio’s age who was considered the supreme master of the male nude during his lifetime, we see that Michelangelo indeed broke with his modern predecessors in his interpretation of the figure. Pollaiuolo’s engraving — included in the Met exhibition, Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer, which runs until February 12 — betrays a lack of resolution in the musculature of the nudes that largely results from a limited ability to subordinate lesser forms to larger ones. His treatment of the musculature of the back, for example, yields a curiously vermiculated topography. Pollaiuolo’s interest in the nude was inspired by antique sculpture and he may even have engaged in dissection, which Michelangelo first practiced as a teenager. But this engraving shows that Pollaiuolo failed to grasp the formal order the Greeks sought in the figure.

Not only does Michelangelo’s mastery of form and composition shine through in his drawings: so does his increasing mastery of draftsmanship as a medium of expression.

Michelangelo’s own breakthrough did not come immediately. No question, his David (1504) is a real hunk. But the modeling lacks the suppleness and complexity of the master’s mature work, in which we do not encounter histrionic gestures like the David’s obviously over-scaled head and right hand holding the stone for the sling at his side. The pose is frontal and the figure lacks the dimensional qualities of The Risen Christ (1521) in Rome’s Santa Maria sopra Minerva or the Victory (1530) in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. (The latter’s triumphant nude has a torsional quality reminiscent of the Belvedere Torso.) The David shows Michelangelo searching for a formal approach that would allow him to endow the nude with terribilità — an awe-inspiring presence. This was the over-arching aim of the master’s career, as the Met exhibition unforgettably demonstrates through the display of 133 of his drawings, including compositional sketches, more or less detailed figure studies, and highly finished works he created for his closest friends — plus a variety of architectural sketches and designs. This quest is what led him to lavish close attention on Hellenistic sculpture — that is, Greek sculpture created and copied after the death of Alexander the Great and throughout most of the Roman imperial era.

It was in painting rather than his principal métier, sculpture carved in marble, that Michelangelo first demonstrated a stupendous mastery of monumental form in a major work of art. This was the Sistine Chapel ceiling, commissioned by Pope Julius II, on which the master labored over a four-year period, creating an elaborate, illusionistic architectural framework for a highly complex portrayal of Old Testament personages and events as the prelude to the gospel of salvation revealed in Christ. This 1,754-square-foot opus — a quarter-scale photographic reproduction of which the Met has very helpfully hung above an exhibition space where preparatory studies are displayed — demanded brutally taxing physical exertion on Michelangelo’s part, but it ranks as painting’s most universally significant achievement. The Met happens to be the proud possessor of a superb sheet of studies in red chalk for the Libyan Sibyl, one of the five pagan prophets on the ceiling reputed to have foreseen the Messiah’s coming. Like many of Michelangelo’s female figures, the ceiling’s Libyan Sibyl is somewhat androgynous, and the model employed for the Met sheet was a young man. In the sheet’s principal study, we see the model’s back in three-quarter view. The detailed rendering of his highly complex anatomical structure — less emphatically treated in the painted Sibyl’s exposed upper torso — makes Pollaiuolo’s engraving look like child’s play. The Sibyl’s pose allows for a beautiful articulation of her feet and, less visibly, hands, with which she takes hold of a sacred tome. Her left foot and hand are analyzed exquisitely in the Met sheet.

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, ca. 1510–11. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1924)

This sheet offers insight into what Michelangelo learned from the ancients as well as what he learned from dissection. The heart-like shape of the model’s left deltoid, or shoulder muscle, corresponds to the shape of the group of small muscles at the base of the model’s thumb, adjoining the palm. This is not a coincidence. It is a technique developed by Greek sculptors. A gifted Baltimore sculptor, Brad Parker, refers to this technique as “shape orientation.” It allowed Michelangelo, who surely had other such correspondences in mind as he drew from the model for the Sibyl, to heighten his figures’ organic coherence.

The drawing on this sheet is not naturalistic. Like so much of Michelangelo’s draftsmanship, it reflects observation of the model transfigured by a sculptural consciousness of form. Sculpture for Michelangelo was the definitive art. Hence his decidedly ambivalent opinion of Titian. He admired Titian’s enchanting palette and “very beautiful and lively manner,” according to Vasari, but lamented that the Venetians were not properly trained in drawing. The gist of his criticism was that Titian lacked the mastery of form resulting from close study, early on, of antique sculpture and the work of moderns who emulated it. This criticism epitomizes the familiar dichotomy between the formal, more sculptural orientation of the Florentines and the Venetians’ typically pictorial mindset, which not even Michelangelo’s example could undermine.

Even so, the Met exhibit fleshes out Michelangelo’s remarkable interaction with the Venice-born-and-bred painter Sebastiano del Piombo. Michelangelo attempted, with only limited success, to establish Sebastiano as a rival to Raphael. The exhibit includes figure studies the master made for his Venetian understudy, who put them to impressive use in remarkably distinctive works, including the Viterbo Pietà (1516) and The Raising of Lazarus (1520). It also includes drawings by Sebastiano that incorporate Michelangelesque concepts of monumental form while retaining painterly qualities that were distinctively Venetian.

Not only does Michelangelo’s mastery of form and composition shine through in his drawings: so does his increasing mastery of draftsmanship as a medium of expression. Looking at earlier drawings, including his studies for the Libyan Sibyl and other figures on the Sistine Chapel ceiling — such as its highly sculptural male nudes, or ignudi, whose varied poses reflect the shifting emotional states bound up in our mortal coil — we can get a good idea of how Michelangelo created them. First of all, they display clearly delineated contours, which Michelangelo emphasized, or not, depending on how hard he pressed down on the chalk. For modeling in light and shade within those contours, he relied on the use of hatching, or parallel strokes, along with cross-hatching, meaning a web-like complex of intersecting strokes. He would modulate the direction and density of the hatching and even the tone of individual strokes to articulate anatomical transitions, always following the form rather than the light or the shade. The hatching could also be modulated to indicate forms only summarily or to reveal them in detail. Michelangelo is famous, after all, for bringing individual figures to a partial state of completion. For highlights he variously resorted to touches of white gouache or white chalk — or simply left the paper blank.

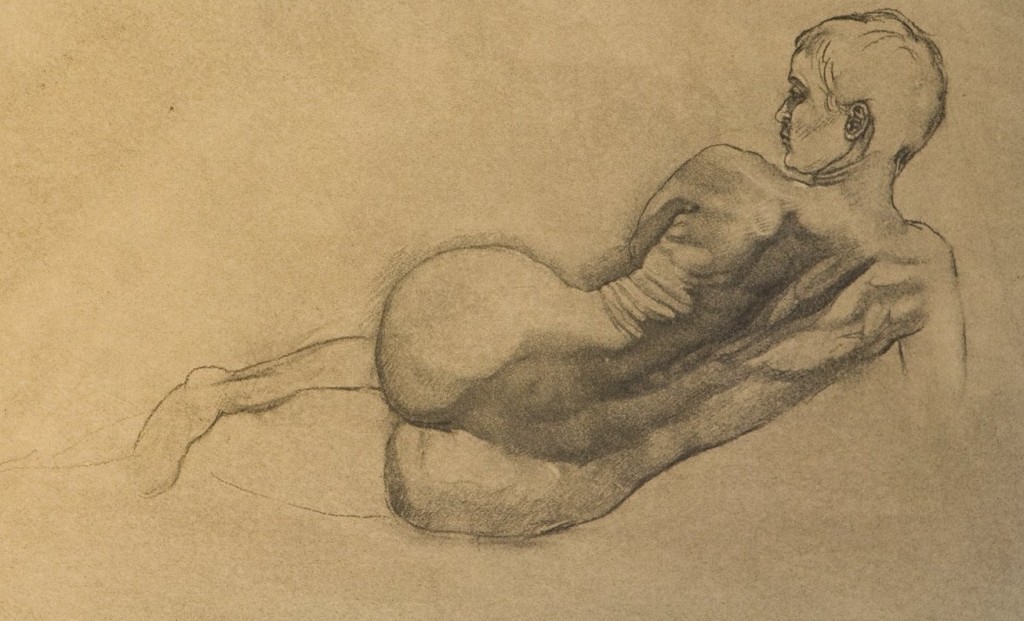

Just using red chalk, with the limited aid of gouache or chalk highlights, Michelangelo could endow portions of figures like the Libyan Sibyl with an almost marmoreal brilliance. This effect is even more strikingly achieved by the Unfinished Cartoon of the Virgin and Child from the mid 1520s, in which the Christ child turns to suckle at his mother’s breast, a pose akin to that in the unfinished Madonna and Child (1534) sculpture in the New Sacristy. Michelangelo fleshed out the child’s torso and right arm with brown wash and gouache highlights as well as red and black chalk, thereby endowing him not with an infant’s pudgy flesh but with a decidedly statuesque musculature. In the most finished portions of the Christ figure, it becomes difficult to detect individual strokes of the master’s hand. And when we arrive at exquisitely finished drawings Michelangelo made during the 1530s, using only black chalk, we encounter decidedly sculptural figures whose contours are well defined but in which individual modeling strokes have given way to a delicate sfumato texture that makes us wonder how the drawings were made. Examples include Michelangelo’s portrait of his young friend Andrea Quaratesi, his mythical Tityus being tormented by the vulture, and the protagonist in his spell-binding allegory, The Dream. This texture, Met curator Carmen C. Bambach informs us in her superb book for the exhibition, is attributable to Michelangelo’s masterful blending of his strokes by rubbing or stumping them.

Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1532. (The British Museum, London)

Il Sogno (The Dream), by Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1530s (London, Courtauld Gallery, Prince Gate Bequest, 1978)

The Met exhibition includes three minor sculptures by Michelangelo, though the attribution of only two of them is certain. (Some doubt he carved the Young Archer, supposedly an early work.) It does put his impressively conceived but unfinished 1540s bust of Brutus, Julius Caesar’s nemesis, to instructive use by juxtaposing it with a Tuscan contemporary’s belabored bust of Caesar and a technically subpar late Hellenistic bust of the emperor Caracalla. But none of the three sculptures, which include an unfinished Apollo or David figure, provides even an inkling of the power of Michelangelo’s masterworks, such as the four recumbent Times of Day figures in the New Sacristy.

Michelangelo’s mastery of form yielded an increasingly inventive approach to architecture, an art to which he only began to devote sustained attention in his early 40s. He came to see architecture as a kind of abstract sculptural expression in its own right. Hence, for example, the strikingly sculptural articulation of his vestibule for the library at San Lorenzo. The vestibule’s constricted space is seized by the most gloriously ADA-noncompliant staircase ever created. Constructed a quarter-century after Michelangelo left Florence for good in 1534, it has justly been compared to a cascading lava flow.

In working on St. Peter’s in Rome for almost two decades prior to his death, Michelangelo again eschewed clutter for a supremely dignified clarity of form and space, thereby transforming, and vastly improving upon, the overly elaborate design he inherited from Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. In this case visitors aren’t given the wherewithal to make detailed comparisons as with the Brutus bust. But we do see Michelangelo improving on his own concept for a centrally planned church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini at Rome. His earlier plan entails superimposition of a circular domed structure enclosing the church’s main space on a square mass. The ingenious but unrealized final design, produced just a few years before his death, resolves that plan’s schematic geometry into a quatrefoil fused with four shallow projections on the cardinal axes. The brilliant, abstractly figural quality of the forms and spaces thus created fortunately was not lost on architects of the baroque period.

* * *

We encounter the shape orientation of the Libyan Sibyl study in the Elgin Marbles, and the Parthenon’s slightly tilted columns and their minute curvature in profile make a distinctly sculptural impression of compressed internal energy, which one art historian likened to that of a crouching lion waiting to pounce. Michelangelo never saw the Marbles or the temple, but he grasped the Greeks’ essential artistic motives while investing them with the force of his own creative genius as no modern had done before and none has done since. Like that of the Belvedere Torso, the structure of his most monumental figures seemingly radiates from an internal nucleus or core like some mysterious geological event. And like the best Greek artists, Michelangelo was well aware of the role of light and shade in communicating form, but understood that form itself must logically, indeed ontologically, come before light and shade.

Rubens’s draftsmanship was famously influenced by Michelangelo’s. But we see powerful echoes of the master in Caravaggio’s sculpturally informed oeuvre as well. Both the pose and the anatomical rigor of the latter’s superb Cupid figure in Amor Vincit Omnia (1603) hearken back to the Sistine Chapel ignudi and other Michelangelo creations. His powerful Flagellation of Christ (1607) recalls Sebastiano’s Flagellation mural (ca. 1520), which Michelangelo helped design, in the church of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. The treatment of Christ’s distended neck in the Caravaggio Flagellation is itself distinctly Michelangelesque. That Caravaggio was imbued with a realist sensibility Michelangelo lacked is beside the point.

Few artists could be expected to successfully incorporate Michelangelo’s formal ideas into their work, because of the level of intellect and discipline that required. Bernini’s long career would follow an increasingly pictorial, even scenographic, trajectory. Further on, Canova would develop a facile, highly stylized idiom whose main feature was the play of light and shade on his static, generic, highly polished marble surfaces. Optical surface effects rather than a sculptural topography articulating internal anatomic structure likewise characterize Rodin’s histrionic attempts to redefine Michelangelo’s sculptural terribilità. Photography, which appeared on the scene around the time Rodin was born, played a decisive role in burying the classical concept of the human figure as a thing-in-itself of great complexity. The figure was thereafter condemned, like everything else within the artist’s purview, to the status of an optical byproduct of reflected light, and academic training swiftly accommodated the new dispensation.

That dispensation, and the dumbed-down approach to drawing the figure it nurtured, is very obvious in the academic studies produced by the young Picasso. A recent exhibition at the Frick Collection in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., was organized on the risible proposition that the academic training Picasso underwent “had remained relatively unchanged since the Renaissance.” In the exhibition catalog, a Frick senior curator reserved the epithet “one of the world’s greatest draughtsmen” for two artists only — Picasso and Michelangelo.

One can only hope this curator has set aside plenty of time for the Met exhibit.

Catesby Leigh writes about public art and architecture and lives in Washington, D.C.