Philosophy & History related to Hellenistic Influenced Art

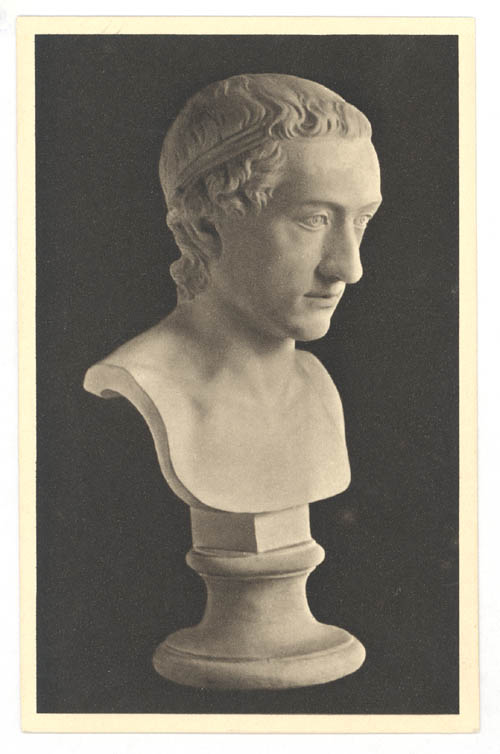

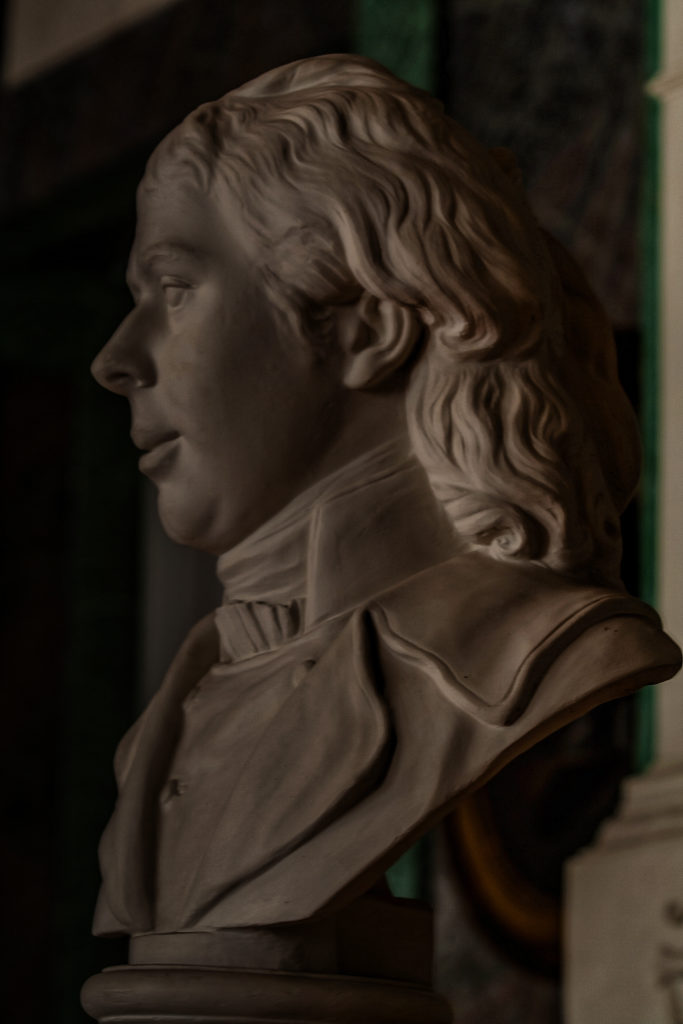

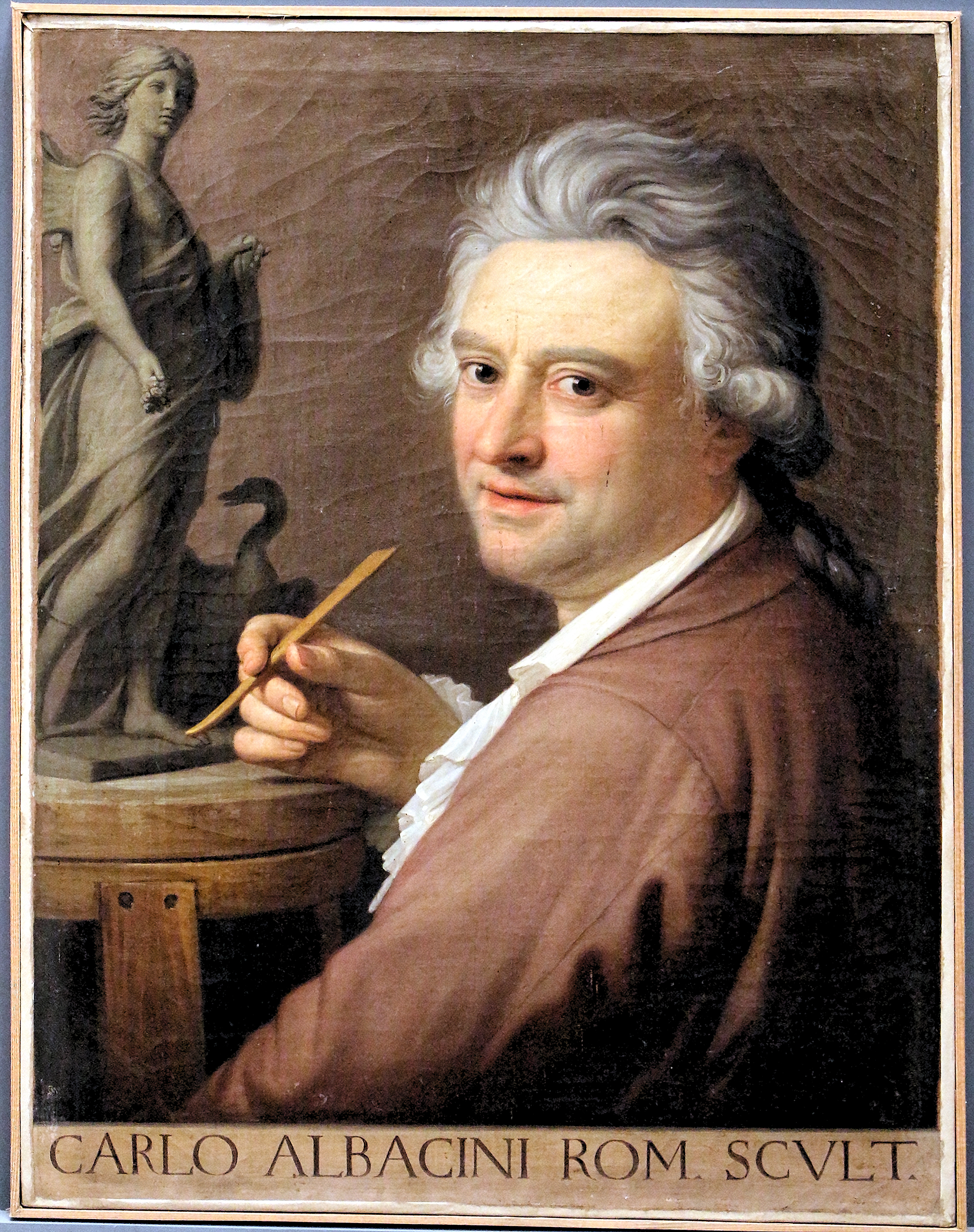

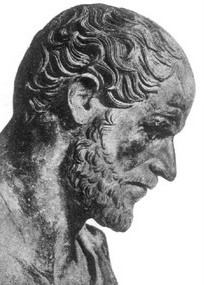

Aristotle

First entry below is from,

Information:

St. John’s College, Annapolis

Aristotle (384-322 BCE.): Ethics

Standard interpretations of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics usually maintain that Aristotle emphasizes the role of habit in conduct. It is commonly thought that virtues, according to Aristotle, are habits and that the good life is a life of mindless routine. These interpretations of Aristotle’s ethics are the result of imprecise translations from the ancient Greek text. Aristotle uses the word hexis to denote moral virtue. But the word does not merely mean passive habituation. Rather, hexis is an active condition, a state in which something must actively hold itself. Virtue, therefore, manifests itself in action. More explicitly, an action counts as virtuous, according to Aristotle, when one holds oneself in a stable equilibrium of the soul, in order to choose the action knowingly and for its own sake. This stable equilibrium of the soul is what constitutes character. Similarly, Aristotle’s concept of the mean is often misunderstood. In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle repeatedly states that virtue is a mean. The mean is a state of clarification and apprehension in the midst of pleasures and pains that allows one to judge what seems most truly pleasant or painful. This active state of the soul is the condition in which all the powers of the soul are at work in concert. Achieving good character is a process of clearing away the obstacles that stand in the way of the full efficacy of the soul. For Aristotle, moral virtue is the only practical road to effective action. What the person of good character loves with right desire and thinks of as an end with right reason must first be perceived as beautiful. Hence, the virtuous person sees truly and judges rightly, since beautiful things appear as they truly are only to a person of good character. It is only in the middle ground between habits of acting and principles of action that the soul can allow right desire and right reason to make their appearance, as the direct and natural response of a free human being to the sight of the beautiful.

Table of Contents (Clicking on the links below will take you to those parts of this article)

1. Habit

In many discussions, the word habit is attached to the Ethics as though it were the answer to a multiple-choice question on a philosophy achievement test. Hobbes’ Leviathan? Self-preservation. Descartes’ Meditations? Mind-body problem. Aristotle’s Ethics? Habit. A faculty seminar I attended a few years ago was mired in the opinion that Aristotle thinks the good life is one of mindless routine. More recently, I heard a lecture in which some very good things were said about Aristotle’s discussion of choice, yet the speaker still criticized him for praising habit when so much that is important in life depends on openness and spontaneity. Can it really be that Aristotle thought life is lived best when thinking and choosing are eliminated? On its face this belief makes no sense. It is partly a confusion between an effect and one of its causes. Aristotle says that, for the way our lives turn out, “it makes no small difference to be habituated this way or that way straight from childhood, but an enormous difference, or rather all the difference.” (1103b, 23-5) Is this not the same as saying those lives are nothing but collections of habits? If this is what sticks in your memory, and leads you to that conclusion, then the cure is easy, since habits are not the only effects of habituation, and a thing that makes all the difference is indispensable but not necessarily the only cause of what it produces.

We will work through this thought in a moment, but first we need to notice that another kind of influence may be at work when you recall what Aristotle says about habit, and another kind of medicine may be needed against it. Are you thinking that no matter how we analyze the effects of habituation, we will never get around the fact that Aristotle plainly says that virtues are habits? The reply to that difficulty is that he doesn’t say that at all. He says that moral virtue is a hexis. Hippocrates Apostle, and others, translate hexis as habit, but that is not at all what it means. The trouble, as so often in these matters, is the intrusion of Latin. The Latin habitus is a perfectly good translation of the Greek hexis, but if that detour gets us to habit in English we have lost our way. In fact, a hexis is pretty much the opposite of a habit.

The word hexis becomes an issue in Plato’s Theaetetus. Socrates makes the point that knowledge can never be a mere passive possession, stored in the memory the way birds can be put in cages. The word for that sort of possession, ktÎsis, is contrasted with hexis, the kind of having-and-holding that is never passive but always at work right now. Socrates thus suggests that, whatever knowledge is, it must have the character of a hexis in requiring the effort of concentrating or paying attention. A hexis is an active condition, a state in which something must actively hold itself, and that is what Aristotle says a moral virtue is.

Some translators make Aristotle say that virtue is a disposition, or a settled disposition. This is much better than calling it a habit, but still sounds too passive to capture his meaning. In De Anima, when Aristotle speaks of the effect produced in us by an object of sense perception, he says this is not a disposition (diathesis) but a hexis. (417b, 15-17) His whole account of sensing and knowing depends on this notion that receptivity to what is outside us depends on an active effort to hold ourselves ready. In Book VII of the Physics, Aristotle says much the same thing about the way children start to learn: they are not changed, he says, nor are they trained or even acted upon in any way, but they themselves get straight into an active state when time or adults help them settle down out of their native condition of disorder and distraction. (247b, 17-248a, 6) Curtis Wilson once delivered a lecture here at St. John’s College, in which he asked his audience to imagine what it would be like if we had to teach children to speak by deliberately and explicitly imparting everything they had to do. We somehow set them free to speak, and give them a particular language to do it in, but they–Mr. Wilson called them little geniuses–they do all the work.

Everyone at St. John’s has thought about the kind of learning that does not depend on the authority of the teacher and the memory of the learner. In the Meno it is called recollection; Aristotle says that it is an active knowing that is always already at work in us. In Plato’s image we draw knowledge up out of ourselves; in Aristotle’s metaphor we settle down into knowing. In neither account is it possible for anyone to train us, as Gorgias has habituated Meno into the mannerisms of a knower. Habits can be strong but they never go deep. Authentic knowledge does engage the soul in its depths, and with this sort of knowing Aristotle links virtue. In the passage cited from Book VII of the Physics, he says that, like knowledge, virtues are not imposed on us as alterations of what we are; that would be, he says, like saying we alter a house when we put a roof on it. In the Categories, knowledge and virtue are the two examples he gives of what hexis means (8b, 29); there he says that these active states belong in the general class of dispositions, but are distinguished by being lasting and durable. The word disposition by itself, he reserves for more passive states, easy to remove and change, such as heat, cold, and sickness.

In the Ethics, Aristotle identifies moral virtue as a hexis in Book II, chapter 4. He confirms this identity by reviewing the kinds of things that are in the soul, and eliminating the feelings and impulses to which we are passive and the capacities we have by nature, but he first discovers what sort of thing a virtue is by observing that the goodness is never in the action but only in the doer. This is an enormous claim that pervades the whole of the Ethics, and one that we need to stay attentive to. No action is good or just or courageous because of any quality in itself. Virtue manifests itself in action, Aristotle says, only when one acts while holding oneself in a certain way. This is where the word hexis comes into the account, from pÙs echÙn, the stance in which one holds oneself when acting. The indefinite adverb is immediately explained: an action counts as virtuous when and only when one holds oneself in a stable equilibrium of the soul, in order to choose the action knowingly and for its own sake. I am translating as “in a stable equilibrium” the words bebaiÙs kai ametakinÍtÙs; the first of these adverbs means stably or after having taken a stand, while the second does not mean rigid or immovable, but in a condition from which one can’t be moved all the way over into a different condition. It is not some inflexible adherence to rules or duty or precedent that is conveyed here, but something like a Newton’s wheel weighted below the center, or one of those toys that pops back upright whenever a child knocks it over. This stable equilibrium of the soul is what we mean by having character. It is not the result of what we call conditioning. There is a story told about B. F. Skinner, the psychologist most associated with the idea of behavior modification, that a class of his once trained him to lecture always from one corner of the room, by smiling and nodding whenever he approached it, but frowning and faintly shaking their heads when he moved away from it. That is the way we acquire habits. We slip into them unawares, or let them be imposed on us, or even impose them on ourselves. A person with ever so many habits may still have no character. Habits make for repetitive and predictable behavior, but character gives moral equilibrium to a life. The difference is between a foolish consistency wholly confined to the level of acting, and a reliability in that part of us from which actions have their source. Different as they are, though, character and habit sound to us like things that are linked, and in Greek they differ only by the change of an epsilon to an eta, making Íthos from ethos We are finally back to Aristotle’s claim that character, Íthos, is produced by habit, ethos. It should now be clear though, that the habit cannot be any part of that character, and that we must try to understand how an active condition can arise as a consequence of a passive one, and why that active condition can only be attained if the passive one has come first. So far we have arranged three notions in a series, like rungs of a ladder: at the top are actives states, such as knowledge, the moral virtues, and the combination of virtues that makes up a character; the middle rung, the mere dispositions, we have mentioned only in passing to claim that they are too shallow and changeable to capture the meaning of virtue; the bottom rung is the place of the habits, and includes biting your nails, twisting your hair, saying “like” between every two words, and all such passive and mindless conditions. What we need to notice now is that there is yet another rung of the ladder below the habits.

We all start out life governed by desires and impulses. Unlike the habits, which are passive but lasting conditions, desires and impulses are passive and momentary, but they are very strong. Listen to a child who can’t live without some object of appetite or greed, or who makes you think you are a murderer if you try to leave her alone in a dark room. How can such powerful influences be overcome? To expect a child to let go of the desire or fear that grips her may seem as hopeless as Aristotle’s example of training a stone to fall upward, were it not for the fact that we all know that we have somehow, for the most part, broken the power of these tyrannical feelings. We don’t expel them altogether, but we do get the upper hand; an adult who has temper tantrums like those of a two-year old has to live in an institution, and not in the adult world. But the impulses and desires don’t weaken; it is rather the case that we get stronger.

Aristotle doesn’t go into much detail about how this happens, except to say that we get the virtues by working at them: in the give-and-take with other people, some become just, others unjust; by acting in the face of frightening things and being habituated to be fearful or confident, some become brave and others cowardly; and some become moderate and gentle, others spoiled and bad-tempered, by turning around from one thing and toward another in the midst of desires and passions. (1103 b, 1422) He sums this up by saying that when we are at-work in a certain way, an active state results. This innocent sentence seems to me to be one of the lynch-pins that hold together the Ethics, the spot that marks the transition from the language of habit to the language appropriate to character. If you read the sentence in Greek, and have some experience of Aristotle’s other writings, you will see how loaded it is, since it says that a hexis depends upon an energeia. The latter word, that can be translated as being-at-work, cannot mean mere behavior, however repetitive and constant it may be. It is this idea of being-at-work, which is central to all of Aristotle’s thinking, that makes intelligible the transition out of childhood and into the moral stature that comes with character and virtue. (See

Aristotle on Motion and its Place in Nature for as discussion energeia. -ed.)

The moral life can be confused with the habits approved by some society and imposed on its young. We at St. John’s College still stand up at the beginning and end of Friday-night lectures because Stringfellow Barr — one of the founders of the current curriculum — always stood when anyone entered or left a room. What he considered good breeding is for us mere habit; that becomes obvious when some student who stood up at the beginning of a lecture occasionally gets bored and leaves in the middle of it. In such a case the politeness was just for show, and the rudeness is the truth. Why isn’t all habituation of the young of this sort? When a parent makes a child repeatedly refrain from some desired thing, or remain in some frightening situation, the child is beginning to act as a moderate or brave person would act, but what is really going on within the child? I used to think that it must be the parent’s approval that was becoming stronger than the child’s own impulse, but I was persuaded by others in a study group that this alone would be of no lasting value, and would contribute nothing to the formation of an active state of character. What seems more likely is that parental training is needed only for its negative effect, as a way of neutralizing the irrational force of impulses and desires.

We all arrive on the scene already habituated, in the habit, that is, of yielding to impulses and desires, of instantly slackening the tension of pain or fear or unfulfilled desire in any way open to us, and all this has become automatic in us before thinking and choosing are available to us at all. This is a description of what is called human nature, though in fact it precedes our access to our true natural state, and blocks that access. This is why Aristotle says that “the virtues come about in us neither by nature nor apart from nature” (1103a, 24-5). What we call human nature, and some philosophers call the state of nature, is both natural and unnatural; it is the passive part of our natures, passively reinforced by habit. Virtue has the aspect of a second nature, because it cannot develop first, nor by a continuous process out of our first condition. But it is only in the moral virtues that we possess our primary nature, that in which all our capacities can have their full development. The sign of what is natural, for Aristotle, is pleasure, but we have to know how to read the signs. Things pleasant by nature have no opposite pain and no excess, because they set us free to act simply as what we are (1154b, 15-21), and it is in this sense that Aristotle calls the life of virtue pleasant in its own right, in itself (1099a, 6-7, 16-17). A mere habit of acting contrary to our inclinations cannot be a virtue, by the infallible sign that we don’t like it.

Our first or childish nature is never eradicated, though, and this is why Aristotle says that our nature is not simple, but also has in it something different that makes our happiness assailable from within, and makes us love change even when it is for the worse. (1154b, 21-32) But our souls are brought nearest to harmony and into the most durable pleasures only by the moral virtues. And the road to these virtues is nothing fancy, but is simply what all parents begin to do who withhold some desired thing from a child, or prevent it from running away from every irrational source of fear. They make the child act, without virtue, as though it had virtue. It is what Hamlet describes to his mother, during a time that is out of joint, when a son must try to train his parent (III, Ìv,181-9):

Assume a virtue if you have it not. That monster, custom, who all sense doth eat Of habits evil, is angel yet in this, That to the use of actions fair and good He likewise gives a frock or livery, That aptly is put on. Refrain tonight, And that shall lend a kind of easiness To the next abstinence; the next more easy; For use almost can change the stamp of nature…

Hamlet is talking to a middle-aged woman about lust, but the pattern applies just as well to five-year-olds and candy. We are in a position to see that it is not the stamp of nature that needs to be changed but the earliest stamp of habit. We can drop Hamlet’s “almost” and rid his last quoted line of all paradox by seeing that the reason we need habit is to change the stamp of habit. A habit of yielding to impulse can be counteracted by an equal and opposite habit. This second habit is no virtue, but only a mindless inhibition, an automatic repressing of all impulses. Nor do the two opposite habits together produce virtue, but rather a state of neutrality. Something must step into the role previously played by habit, and Aristotle’s use of the word energeia suggests that this happens on its own, with no need for anything new to be imposed. Habituation thus does not stifle nature, but rather lets nature make its appearance. The description from Book VII of the Physics of the way children begin to learn applies equally well to the way human character begins to be formed: we settle down, out of the turmoil of childishness, into what we are by nature.

We noticed earlier that habituation is not the end but the beginning of the progress toward virtue. The order of states of the soul given by Aristotle went from habit to being-at-work to the hexis or active state that can give the soul moral stature. If the human soul had no being-at-work, no inherent and indelible activity, there could be no such moral stature, but only customs. But early on, when first trying to give content to the idea of happiness, Aristotle asks if it would make sense to think that a carpenter or shoemaker has work to do, but a human being as such is inert. His reply, of course, is that nature has given us work to do, in default of which we are necessarily unhappy, and that work is to put into action the power of reason. (1097b, 24-1098a, 4) Note please that he does not say that everyone must be a philosopher, nor even that human life is constituted by the activity of reason, but that our work is to bring the power of logos forward into action. Later, Aristotle makes explicit that the irrational impulses are no less human than reasoning is. (1111 b, 1-2) His point is that, as human beings, our desires need not be mindless and random, but can be transformed by thinking into choices, that is desires informed by deliberation. (1113a, 11) The characteristic human way of being-at-work is the threefold activity of seeing an end, thinking about means to it, and choosing an action. Responsible human action depends upon the combining of all the powers of the soul: perception, imagination, reasoning, and desiring. These are all things that are at work in us all the time. Good parental training does not produce them, or mold them, or alter them, but sets them free to be effective in action. This is the way in which, according to Aristotle, despite the contributions of parents, society, and nature, we are the co-authors of the active states of our own souls. (1114b, 23-4)

2. The Mean

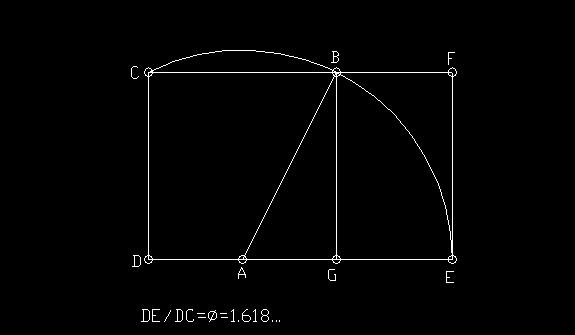

Now this discussion has shown that habit does make all the difference to our lives without being the only thing shaping those lives and without being the final form they take. The same discussion also points to a way to make some sense of one of the things that has always puzzled me most in the Ethics, the insistence that moral virtue is always in its own nature a mean condition. Quantitative relations are so far from any serious human situation that they would seem to be present only incidentally or metaphorically, but Aristotle says that “by its thinghood and by the account that unfolds what it is for it to be, virtue is a mean.” (1107a, 7-8) This invites such hopeless shallowness as in the following sentences that I quote from a recent article in a journal called Ancient Philosophy (Vol. 8, pp. 101-4): “To illustrate …0 marks the mean (e.g. Courage); …Cowardice is -3 while Rashness is 3…In our number language…’Always try to lower the absolute value of your vice.’ ” This scholar thinks achieving courage is like tuning in a radio station on an analog dial. Those who do not sink this low might think instead that Aristotle is praising a kind of mediocrity, like that found in those who used to go to college to get gentlemen’s C’s. But what sort of courage could be found in these timid souls, whose only aim in life is to blend so well into their social surroundings that virtue can never be chosen in preference to a fashionable vice? Aristotle points out twice that every moral virtue is an extreme (1107a, 8-9, 22-4), but he keeps that observation secondary to an over-riding sense in which it is a mean. Could there be anything at all to the notion that we hone in on a virtue from two sides? There is a wonderful image of this sort of thing in the novel Nop’s Trials by Donald McCaig. The protagonist is not a human being, but a border collie named Nop. The author describes the way the dog has to find the balance point, the exact distance behind a herd of sheep from which he can drive the whole herd forward in a coherent mass. When the dog is too close, the sheep panic and run off in all directions; when he is too far back, the sheep ignore him, and turn in all directions to graze. While in motion, a good working dog keeps adjusting his pace to maintain the exact mean position that keeps the sheep stepping lively in the direction he determines. Now working border collies are brave, tireless, and determined. They have been documented as running more than a hundred miles in a day, and they love their work. There is no question that they display virtue, but it is not human virtue and not even of the same form. Some human activities do require the long sustained tension a sheep dog is always holding on to, an active state stretched to the limit, constantly and anxiously kept in balance. Running on a tightrope might capture the same flavor. But constantly maintained anxiety is not the kind of stable equilibrium Aristotle attributes to the virtuous human soul.

I think we may have stumbled on the way that human virtue is a mean when we found that habits were necessary in order to counteract other habits. This does accord with the things Aristotle says about straightening warped boards, aiming away from the worse extreme, and being on guard against the seductions of pleasure. (1109a, 30- b9) The habit of abstinence from bodily pleasure is at the opposite extreme from the childish habit of yielding to every immediate desire. Alone, either of them is a vice, according to Aristotle. The glutton, the drunkard, the person enslaved to every sexual impulse obviously cannot ever be happy, but the opposite extremes, which Aristotle groups together as a kind of numbness or denial of the senses (1107b, 8), miss the proper relation to bodily pleasure on the other side. It may seem that temperance in relation to food, say, depends merely on determining how many ounces of chocolate mousse to eat. Aristotle’s example of Milo the wrestler, who needs more food than the rest of us do to sustain him, seems to say this, but I think that misses the point. The example is given only to show that there is no single action that can be prescribed as right for every person and every circumstance, and it is not strictly analogous even to temperance with respect to food. What is at stake is not a correct quantity of food but a right relation to the pleasure that comes from eating.

Suppose you have carefully saved a bowl of chocolate mousse all day for your mid-evening snack, and just as you are ready to treat yourself, a friend arrives unexpectedly to visit. If you are a glutton, you might hide the mousse until the friend leaves, or gobble it down before you open the door. If you have the opposite vice, and have puritanically suppressed in yourself all indulgence in the pleasures of food, you probably won’t have chocolate mousse or any other treat to offer your visitor. If the state of your soul is in the mean in these matters, you are neither enslaved to nor shut out from the pleasure of eating treats, and can enhance the visit of a friend by sharing them. What you are sharing is incidentally the 6 ounces of chocolate mousse; the point is that you are sharing the pleasure, which is not found on any scale of measurement. If the pleasures of the body master you, or if you have broken their power only by rooting them out, you have missed out on the natural role that such pleasures can play in life. In the mean between those two states, you are free to notice possibilities that serve good ends, and to act on them. It is worth repeating that the mean is not the 3 ounces of mousse on which you settled, since if two friends had come to visit you would have been willing to eat 2 ounces. That would not have been a division of the food but a multiplication of the pleasure. What is enlightening about the example is how readily and how nearly universally we all see that sharing the treat is the right thing to do. This is a matter of immediate perception, but it is perception of a special kind, not that of any one of the five senses, Aristotle says, but the sort by which we perceive that a triangle is the last kind of figure into which a polygon can be divided. (1142a, 28-30) This is thoughtful and imaginative perceiving, but it has to be perceived. The childish sort of habit clouds our sight, but the liberating counter-habit clears that sight. This is why Aristotle says that the person of moral stature, the spoudaios, is the one to whom things appear as they truly are. (1113a, 30-1) Once the earliest habits are neutralized, our desires are disentangled from the pressure for immediate gratification, we are calm enough to think, and most important, we can see what is in front of us in all its possibility. The mean state here is not a point on a dial that we need to fiddle up and down; it is a clearing in the midst of pleasures and pains that lets us judge what seems most truly pleasant and painful.

Achieving temperance toward bodily pleasures is, by this account, finding a mean, but it is not a simple question of adjusting a single varying condition toward the more or the less. The person who is always fighting the same battle, always struggling like the sheep dog to maintain the balance point between too much and too little indulgence, does not, according to Aristotle, have the virtue of temperance, but is at best self restrained or continent. In that case, the reasoning part of the soul is keeping the impulses reined in. But those impulses can slip the reins and go their own way, as parts of the body do in people with certain disorders of the nerves. (1102b, 14-22) Control in self-restrained people is an anxious, unstable equilibrium that will lapse whenever vigilance is relaxed. It is the old story of the conflict between the head and the emotions, never resolved but subject to truces. A soul with separate, self-contained rational and irrational parts could never become one undivided human being, since the parties would always believe they had divergent interests, and could at best compromise. The virtuous soul, on the contrary, blends all its parts in the act of choice. This, I think, is the best way to understand the active state of the soul that constitutes moral virtue and forms character. It is the condition in which all the powers of the soul are at work together, making it possible for action to engage the whole human being. The work of achieving character is a process of clearing away the obstacles that stand in the way of the full efficacy of the soul. Someone who is partial to food or drink, or to running away from trouble or to looking for trouble, is a partial human being. Let the whole power of the soul have its influence, and the choices that result will have the characteristic look that we call courage or temperance or simply virtue. Now this adjective “characteristic” comes from the Greek word charactÍr, which means the distinctive mark scratched or stamped on anything, and which to my knowledge is never used in the Nicomachean Ethics. In the sense of character of which we are speaking, the word for which is Íthos, we see an outline of the human form itself. A person of character is someone you can count on, because there is a human nature in a deeper sense than that which refers to our early state of weakness. Someone with character has taken a stand in that fully mature nature, and cannot be moved all the way out of it.

But there is also such a thing as bad character, and this is what Aristotle means by vice, as distinct from bad habits or weakness. It is possible for someone with full responsibility and the free use of intellect to choose always to yield to bodily pleasure or to greed. Virtue is a mean, first because it can only emerge out of the stand-off between opposite habits, but second because it chooses to take its stand not in either of those habits but between them. In this middle region, thinking does come into play, but it is not correct to say that virtue takes its stand in principle; Aristotle makes clear that vice is a principled choice that following some extreme path toward or away from pleasure is right. (1146b, 22-3) Principles are wonderful things, but there are too many of them, and exclusive adherence to any one of them is always a vice.

In our earlier example, the true glutton would be someone who does not just have a bad habit of always indulging the desire for food, but someone who has chosen on principle that one ought always to yield to it. In Plato’s Gorgias, Callicles argues just that, about food, drink, and sex. He is serious, even though he is young and still open to argument. But the only principled alternative he can conceive is the denial of the body, and the choice of a life fit only for stones or corpses. (492E) This is the way most attempts to be serious about right action go astray. What, for example, is the virtue of a seminar leader? Is it to ask appropriate questions but never state an opinion? Or is it to offer everything one has learned on the subject of discussion? What principle should rule?–that all learning must come from the learners, or that without prior instruction no useful learning can take place? Is there a hybrid principle? Or should one try to find the mid-way point between the opposite principles? Or is the virtue some third kind of thing altogether?

Just as habits of indulgence always stand opposed to habits of abstinence, so too does every principle of action have its opposite principle. If good habituation ensures that we are not swept away by our strongest impulses, and the exercise of intelligence ensures that we will see two worthy sides to every question about action, what governs the choice of the mean? Aristotle gives this answer: “such things are among particulars, and the judgment is in the act of sense-perception.” (1109b, 23-4) But this is the calmly energetic, thought-laden perception to which we referred earlier. The origin of virtuous action is neither intellect nor appetite, but is variously described as intellect through-and-through infused with appetite, or appetite wholly infused with thinking, or appetite and reason joined for the sake of something; this unitary source is called by Aristotle simply anthropos. (1139a, 34, b, S-7) But our thinking must contribute right reason (ho orthos logos) and our appetites must contribute right desire (hÍ orthÍ orexis) if the action is to have moral stature. (1114b, 29, 1139a, 24-6, 31-2) What makes them right can only be the something for the sake of which they unite, and this is what is said to be accessible only to sense perception. This brings us to the third word we need to think about.

Back to Table of Contents3. Noble

Aristotle says plainly and repeatedly what it is that moral virtue is for the sake of, but the translators are afraid to give it to you straight. Most of them say it is the noble. One of them says it is the fine. If these answers went past you without even registering, that is probably because they make so little sense. To us, the word noble probably connotes some sort of high-minded naivetÈ, something hopelessly impractical. But Aristotle considers moral virtue the only practical road to effective action. The word fine is of the same sort but worse, suggesting some flimsy artistic soul who couldn’t endure rough treatment, while Aristotle describes moral virtue as the most stable and durable condition in which we can meet all obstacles. The word the translators are afraid of is to kalon, the beautiful. Aristotle singles out as the distinguishing mark of courage, for example, that it is always “for the sake of the beautiful, for this is the end of virtue.” (111 S b, 12-13) Of magnificence, or large-scale philanthropy, he says it is “for the sake of the beautiful, for this is common to the virtues.” (1122 b, 78) What the person of good character loves with right desire and thinks of as an end with right reason must first be perceived as beautiful.

The Loeb translator explains why he does not use the word beautiful in the Nicomachean Ethics. He tells us to kalon has two different uses, and refers both to “(1) bodies well shaped and works of art …well made, and (2) actions well done.” (p. 6) But we have already noticed that Aristotle says the judgment of what is morally right belongs to sense-perception. And he explicitly compares the well made work of art to an act that springs from moral virtue. Of the former, people say that it is not possible add anything to it or take anything from it, and Aristotle says that virtue differs from art in that respect only in being more precise and better. (1106b, 10-15) An action is right in the same way a painting might get everything just right. Antigone contemplates in her imagination the act of burying her brother, and says “it would be a beautiful thing to die doing this.” (Antigone, line 72) This is called courage. Neoptolemus stops Philoctetes from killing Odysseus with the bow he has just returned, and says “neither for me nor for you is this a beautiful thing.” (Philoctetes, line 1304) This is a recognition that the rightness of returning the bow would be spoiled if it were used for revenge. This is not some special usage of the Greek language, but one that speaks to us directly, if the translators let it. And it is not a kind of language that belongs only to poetic tragedy, since the tragedians find their subjects by recognizing human virtue in circumstances that are most hostile to it.

In the most ordinary circumstances, any mother might say to a misbehaving child, in plain English, “don’t be so ugly.” And any of us, parent, friend, or grudging enemy, might on occasion say to someone else, “that was a beautiful thing you did.” Is it by some wild coincidence that twentieth-century English and fourth-century BC Greek link the same pair of uses under one word? Aristotle is always alert to the natural way that important words have more than one meaning. The inquiry in his Metaphysics is built around the progressive narrowing of the word being until its primary meaning is discovered. In the Physics the various senses of motion and change are played on like the keyboard of a piano, and serve to uncover the double source of natural activity. The inquiry into ethics is not built in this fashion; Aristotle asks about the way the various meanings of the good are organized, but he immediately drops the question, as being more at home in another sort of philosophic inquiry. (1096b, 26-32) It is widely claimed that Aristotle says there is no good itself, or any other form at all of the sort spoken of in Plato’s dialogues. This is a misreading of any text of Aristotle to which it is referred. Here in the study of ethics it is a failure to see that the idea of the good is not rejected simply, but only held off as a question that does not arise as first for us. Aristotle praises Plato for understanding that philosophy does not argue from first principles but toward them. (1095a, 31-3) But while Aristotle does not make the meanings of the good an explicit theme that shapes his inquiry, he nevertheless does plainly lay out its three highest senses, and does narrow down the three into two and indirectly into one. He tells us there are three kinds of good toward which our choices look, the pleasant, the beautiful, and the beneficial or advantageous. (1104b, 31-2) The last of these is clearly subordinate to the other two, and when the same issue comes up next, it has dropped out of the list. The goods sought for their own sake are said to be of only two kinds, the pleasant and the beautiful. (1110b, 9-12) That the beautiful is the primary sense of the good is less obvious, both because the pleasant is itself resolved into a variety of senses, and because a whole side of virtue that we are not considering in this lecture aims at the true, but we can sketch out some ways in which the beautiful emerges as the end of human action. Aristotle’s first description of moral virtue required that the one acting choose an action knowingly, out of a stable equilibrium of the soul, and for its own sake. The knowing in question turned out to be perceiving things as they are, as a result of the habituation that clears our sight. The stability turned out to come from the active condition of all the powers of the soul, in the mean position opened up by that same habituation, since it neutralized an earlier, opposite, and passive habituation to self-indulgence. In the accounts of the particular moral virtues, an action’s being chosen for its own sake is again and again specified as meaning chosen for no reason other than that it is beautiful. In Book III, chapter 8, Aristotle refuses to give the name courageous to anyone who acts bravely for the sake of honor, out of shame, from experience that the danger is not as great as it seems, out of spiritedness or anger or the desire for revenge, or from optimism or ignorance. Genuinely courageous action is in no obvious way pleasant, and is not chosen for that reason, but there is according to Aristotle a truer pleasure inherent in it. It doesn’t need pleasure dangled in front of it as an extra added attraction. Lasting and satisfying pleasure never comes to those who seek pleasure, but only to the philokalos, who looks past pleasure to the beautiful. (1099a, 15-17, 13)

In our earlier example of temperance, I think most of us would readily agree that the one who had his eye only the chocolate mousse found less pleasure than the one who saw that it would be a better thing to share it. And Aristotle does say explicitly that the target the temperate person looks to is the beautiful. (1119b, 15-17) But since there are three primary moral virtues, courage, temperance, and justice, it is surprising that in the whole of Book V, which discusses justice, Aristotle never mentions the beautiful. It must somehow be applicable, since he says it is common to all the moral virtues, but in that case it would seem that the account of justice could not be complete if it is not connected to the beautiful. I think this does happen, but in an unexpected way. Justice seems to be not only a moral virtue, but in some pre-eminent way the moral virtue. And Aristotle says that there is a sense of the word in which the one we call just is the person who has all moral virtue, insofar as it affects other people. (1129b, 26-7) In spite of all this, I believe that Aristotle treats justice as something inherently inadequate, a condition of the soul that cannot ever achieve the end at which it aims.

Justice concerns itself with the right distribution of rewards and punishments within a community. This would seem to be the chief aim of the lawmakers, but Aristotle says that they do not take justice as seriously as friendship. They accord friendship a higher moral stature than justice. (1155a, 23-4) It seems to me now that Aristotle does too, and that the discussion of friendship in Books VIII and IX replaces that of justice.

What is the purpose of reward and punishment? I take Aristotle’s answer to be homonoia, the like-mindedness that allows a community to act in concord. For the sake of this end, he says, it is not good enough that people be just, while if they are friends they have no need to be just: (1155a, 24-9) So far, this sounds as though friendship is merely something advantageous for the social or political good, but Aristotle immediately adds that it is also beautiful. The whole account of friendship, you will recall, is structured around the threefold meaning of the good. Friendships are distinguished as being for use, for pleasure, or for love of the friend’s character.

Repeatedly, after raising questions about the highest kind of friendship, Aristotle resolves them by looking to the beautiful: it is a beautiful thing to do favors for someone freely, without expecting a return (1163a, 1, 1168a, 10-13); even in cases of urgent necessity, when there is a choice about whom to benefit, one should first decide whether the scale tips toward the necessary or the beautiful thing (1165a, 4-5 ); to use money to support our parents is always more beautiful than to use it for ourselves (1165a, 22-4); someone who strives to achieve the beautiful in action would never be accused of being selfish (1168b, 25-8). These observations culminate in the claim that, “if all people competed for the beautiful, and strained to do the most beautiful things, everything people need in common, and the greatest good for each in particular, would be achieved …for the person of moral stature will forego money, honor, and all the good things people fight over to achieve the beautiful for himself.” (1169a, 8-11, 20-22) This does not mean that people can do without such things as money and honor, but that the distribution of such things takes care of itself when people take each other seriously and look to something higher.

The description of the role of the beautiful in moral virtue is most explicit in the discussion of courage, where the emphasis is on the great variety of things that resemble courage but fail to achieve it because they are not solely for the sake of the beautiful. That discussion is therefore mostly negative. We can now see that the discussion of justice was also of a negative character, since justice itself resembles the moral virtue called friendship without achieving it, again because it does not govern its action by looking to the beautiful. The discussion of friendship contains the largest collection of positive examples of actions that are beautiful. There is something of a tragic feeling to the account of courage, pointing to the extreme situation of war in which nothing might be left to choose but a beautiful death. But the account of friendship points to the healthy community, in which civil war and other conflicts are driven away by the choice of what is beautiful in life. (1155a, 24-7) By the end of the ninth book, there is no doubt that Aristotle does indeed believe in a primary sense of the good, at least in the human realm, and that the name of this highest good is the beautiful.

And it should be noticed that the beautiful is at work not only in the human realm. In De Anima, Aristotle argues that, while the soul moves itself in the act of choice, the ultimate source of its motion is the practical good toward which it looks, which causes motion while it is itself motionless. (433a, 29-30, b, 11-13) This structure of the motionless first mover is taken up in Book XII of the Metaphysics, where Aristotle argues that the order of the cosmos depends on such a source, which causes motion in the manner of something loved; he calls this source, as one of its names, the beautiful, that which is beautiful not in seeming but in being. (1072a, 26-b, 4) Like Diotima in Plato’s Symposium, Aristotle makes the beautiful the good itself. I want to add just one more word, on the fact that the beautiful in the Ethics is not an object of contemplation simply, but the source of action. In an article on the

Poetics I discussed the intimate connection of beauty with the experience of wonder. The sense of wonder seems to me to be the way of seeing which allows things to appear as what they are, since it holds off our tendencies to make things fit into theories or opinions we already hold, or use things for purposes that have nothing to do with them. But this is what Aristotle says repeatedly is the ultimate effect of moral virtue, that the one who has it sees truly and judges rightly, since only to someone of good character do the things that are beautiful appear as they truly are (1113 a, 29-35), that practical wisdom depends on moral virtue to make its aim right (1144a, 7-9), and that the eye of the soul that sees what is beautiful as the end or highest good of action gains its active state only with moral virtue (1144a, 26-33). It is only in the middle ground between habits of acting and between principles of action that the soul can allow right desire and right reason to make their appearance, as the direct and natural response of a free human being to the sight of the beautiful.

4. References and Further Reading

Aristotle, Metaphysics, Joe Sachs (trans.), Green Lion Press,

1999.Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Joe Sachs (trans.), Focus

Philosophical Library, Pullins Press, 2002.

Aristotle, On the Soul, Joe Sachs (trans.), Green Lion Press, 2001.

Aristotle, Poetics, Joe Sachs (trans.), Focus Philosophical Library,

Pullins Press, 2006.

Aristotle, Physics, Joe Sachs (trans.), Rutgers U. P., 1995.

Author Information:

St. John’s College, Annapolis

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

AESTHETICS,

branch of philosophy concerned with the essence and perception of beauty and ugliness. Aesthetics also deals with the question of whether such qualities are objectively present in the things they appear to qualify or whether they exist only in the mind of the individual; hence, whether objects are perceived by a particular mode, the aesthetic mode, or whether instead the objects have, in themselves, special qualities—aesthetic qualities.

Criticism and the psychology of art, although independent disciplines, are related to aesthetics. The psychology of art is concerned with such elements of the arts as human responses to color, sound, line, form, and words and with the ways in which the emotions condition such responses. Criticism confines itself to particular works of art, analyzing their structures, meanings, and problems, comparing them with other works, and evaluating them.

The term aesthetics was introduced in 1753 by the German philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, but the study of the nature of beauty had been pursued for centuries. In the past it was chiefly a subject for philosophers. Since the 19th century, artists also have contributed their views.

Classical Theories.

The first aesthetic theory of any scope is that of Plato, who believed that reality consists of archetypes, or forms, beyond human sensation, which are the models for all things that exist in human experience. The objects of such experience are examples, or imitations, of those forms. The philosopher tries to reason from the object experienced to the reality it imitates; the artist copies the experienced object, or uses it as a model for the work. Thus, the artist’s work is an imitation of an imitation.

Plato’s thinking had a marked ascetic strain. In his Republic Plato went so far as to banish some types of artists from his ideal society because he thought their work encouraged immorality or portrayed base characters, and that certain musical compositions caused languidness or incited people to immoderate actions. Aristotle also spoke of art as imitation, but not in the Platonic sense. One could imitate “things as they ought to be,” he wrote, and “art partly completes what nature cannot bring to a finish.” The artist separates the form from the matter of some objects of experience, such as the human body or a tree, and imposes that form on another matter, such as canvas or marble. Thus, imitation is not just copying an original model, nor is it devising a symbol for the original; rather, it is a particular representation of an aspect of things, and each work is an imitation of the universal whole.

Aesthetics was as inseparable from morality and politics for Aristotle as for Plato. The former wrote about music in his Politics, maintaining that art affects human character, and hence the social order. Because Aristotle held that happiness is the aim of life, he believed that the major function of art is to provide human satisfaction. In the Poetics, his great work on the principles of drama, Aristotle argued that tragedy so stimulates the emotions of pity and fear, which he considered morbid and unhealthful, that by the end of the play the spectator is purged of them. This catharsis makes the audience psychologically healthier and thus more capable of happiness. Neoclassical drama since the 17th century has been greatly influenced by Aristotle’s Poetics. The works of the French dramatists Jean Baptiste Racine, Pierre Corneille, and Molière, in particular, advocate its doctrine of the three unities: time, place, and action. This concept dominated literary theories up to the 19th century. ‘

Other Early Approaches.

The 3d-century philosopher Plotinus, born in Egypt and trained in philosophy at Alexandria, although a Neoplatonist, gave far more importance to art than did Plato. In Plotinus’s view, art reveals the form of an object more clearly than ordinary experience does, and it raises the soul to contemplation of the universal. According to Plotinus, the highest moments of life are mystical, which is to say that the soul is united, in the world of forms, with the divine, which Plotinus spoke of as “the One.” Aesthetic experience comes closest to mystical experience, for one loses oneself while contemplating the aesthetic object.

Art in the Middle Ages was primarily an expression of religion, with an aesthetic principle based largely on Neoplatonism. During the Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries, art became more secular, and its aesthetics were classical rather than religious. The great impetus to aesthetic thought in the modern world occurred in Germany during the 18th century. The German critic Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, in his Laocoön (1766), argued that art is self-limiting and reaches its apogee only when these limitations are recognized. The German critic and classical archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann maintained that, in accordance with the ancient Greeks, the best art is impersonal, expressing ideal proportion and balance rather than its creator’s individuality. The German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte considered beauty a moral virtue. The artist creates a world in which beauty, as much as truth, is an end, foreshadowing that absolute freedom which is the goal of the human will. For Fichte, art is individual, not social, but it fulfills a great human purpose.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Plotinus

Plotinus–On the Intellectual Beauty Plotinus defends art against the Platonic charge of being 3x removed from reality (and therefore not only useless, but dangerous). In his view, despite the removal, or distance, of art from the One (the source of ideas/forms) it is “not to be slighted on the ground that they [the artists] create by imitation of natural objects.” Instead, the art objects “give no bare reproduction of the thing seen but go back to the reason-principles from which nature itself derives.” Art may actually improve upon the natural world: “they [art objects] are holders of beauty and add where nature is lacking.” Plotinus compares the function of the One as the ultimate source of all things to the function of the artist as a “maker”: “All that comes to be, work of nature or of craft, some wisdom has made: everywhere a wisdom presides as a making.” The artist is not simply imitating objects which are themselves imitations of the ideas springing from the One. The artist has some concept of the idea available to him: “the artist himself goes back, after all, to that wisdom in nature which is embodied in himself.” This statement sounds much like the biological justification made for the Jungian formulation of psychological archetypes; the natural world is itself a reflection of the ideas of the One–we are part of that world, and therefore we are a reflection of the ideas of the One. The artist need not merely copy a bed made by a craftsman; he has the concept of “bedness” available to him already, not through philosophy, but through his very being, his participation in nature. In Plotinus, ultimate knowledge lies in the soul’s ability to contemplate and grasp the world of forms. OK, here we are still with Plato. Here is the essential difference: Plato sees the world and its products as being separated from the One, mere copies of the ideas of the One. Plotinus–if I am understanding him–sees the world and its products as being part of the One, thus not separated from the One and not to be regarded as valueless distractions from the One. In fact a contemplation of the world’s beauty can be the first step toward an eventual contemplation of, and union with, the One. The philosophy is ultimately one of transcendence which does not reify that which is transcended. Art–including poetry–can be a perfectly legitimate path to transcendence. The Plotinian metaphysic is hierarchical. Matter emanates from the Soul, which in turn emanates from the realm of intellect or nouV (nous); at the source of all of these things is the One. Matter, as it looks away from the realm of soul, tends to become disorganized matter (the Plotinian roots of Teilhard de Chardin’s evolutionary theology are clear to me now); when matter is subject to the direction of soul, it exemplifies harmony and order to the highest degree it is capable of attaining (this is why the physical world is not to be despised in the Plotinian system). To the extent that the soul’s attention is focused on matter, it tends to forget itself and become wrapped up in physical desires; but to the extent that the soul turns its attention to the realm of intellect, it is drawn away from merely physical concerns and becomes absorbed in contemplation. The soul, by looking to itself (and here the point Plotinus makes about the artist looking to the forms already present within himself becomes clear) and discovering its higher nature, is led away from the realm of matter to matter’s source–the One.

Michael Bryson;

1.6. Plotinus (205-270 AD)

Plotinus was the founder and main figure of the neoplatonic school. His contribution is not to the theory of literature but to aesthetics in general, underlining the cognitive value of art and its metaphysical implications. His theory of art is accordingly found in his work on metaphysics, the Enneads.

Being is an emanation from and a return to the Divine One. There is this world, an appearance as for Plato, and then Reality, above it. Its grades form a kind of Trinity: Soul , Intellect, and Oneness. “The One expresses itself in a triad, the Good, the Intellect and its return to it. Beauty, as Plotinus laboriously defines it, is central to his system, since the more beautiful a thing is, the closer it is to the One” (Adams 105). The principle which produces Beauty is itself beautiful and close to the One. Wisdom itself is the highest form of beauty. And both are eternal, above the changes in Nature. The Gods do not contemplate processes, but being. Nature, change, process, are the manifestation of the One and of the intellectual realm, of Being. The One is too lofty to be thought of in terms of “beauty”. Beauty belongs rather to the second hypostasis, to the Intellectual realm. Intelligence itself is below the level of the One: Proclus, a disciple of Plotinus, will remark that knowing involves a duality, subject and object. The One can only be reached by negation of differences and not knowing. Beauty lies in the imposition of the artist’s mental form on materials with a struggle. Beauty in art comes from form, and not from the materials. This form is present in the mind of the artist, and is transferred (derivatively and not wholly) to the work. So, the works of art “give no base reproduction of the thing seen but go back to the reason-principles from which Nature itself derives.” Art can provide a valuable, though imperfect, spiritual insight. It improves Nature. Beauty in natural objects comes from the same principles: it is present in the idea, rather than in the actual matter. In the realm of literary criticism, these ideas will contribute to the growth of allegorical interpretation: what is important in the literary work, the neoplatonic critics will argue, is not its matter, its literal meaning, but the idea which organizes the whole and gives the work a spiritual meaning (cf. 1.8).

Art is not a wholly rational kind of knowledge, in the sense that it leads beyond human reason. The way to the One is through inner vision, through the mystical shedding of self. The role of the artist is important, but in the last analysis he is only a channel for Beauty to express itself. The principles of beauty are not dependent on him; they are high above the artist and nature: No doubt the vision of the artist may be the quid of the work; it is sufficient explanation of the wisdom exhibited in the arts; but the artist himself goes back, after all, to that wisdom in nature which is embodied in himself; and this is not a wisdom consisting of a manifold detail coordinated into a unity but rather a unity working out into detail.

The role of the artist is not to create, but to reveal or to reconstruct a unity which is already existent in the realm of ideas. This goes against some of the ideas on unity which we have seen (the Stoics’, for instance, saw beauty in the relationship of parts imposed by the artist). In Plotinian aesthetics, “sheer symmetry is not necessarily, as in earlier Greek aesthetics, a sign of beauty” (Adams 105). Plotinus says that each part of the whole must be a whole in itself, just as each part of the Universe mirrors the structure of the whole. Beauty is often linked to brightness . Good, unity and brightness are in eternal association in the human mind. But true beauty is invisible, it no longer needs sensory beauty.

The aesthetic theory expounded by Plotinus opens the way of the “musician” to the realm of ideas, a way which was closed in the original Platonic theory. Art is for the neoplatonists a cognitive, beneficial, and even divine activity. Neoplatonic philosophy was absorbed by the early Fathers of the Church, and therefore the neoplatonic approach to aesthetics and to the interpretation of literary works was an important influence on Christian thought about art and literature all through the Middle Ages. There are neoplatonic revivals in the Renaissance and in the Romantic age. This mystical and ideal conception of art will reappear in some Romantic poets such as Schlegel, Shelley or Keats.

This quote from “Contemplation” says everything to me about what it means to make art: Were one to ask Nature why it produces, it might-if willing-thus reply:”You should never have put the question. Silently, as I am silent and little given to talk, you should have tried to understand…that what comes to be is the object of my silent contemplation: mine is a contemplative nature. The contemplative in me produces the object contemplated much as geometricians draw their figures while contemplating. I do not draw. But, contemplating, I drop within me the lines constitutive of bodily forms. Within me I preserve traces of my source that brought me into being. They too were born of contemplation and without action on their own part gave birth to me.

Section 1

1. It is a principle with us that one who has attained to the vision of the Intellectual Beauty and grasped the beauty of the Authentic Intellect will be able also to come to understand the Father and Transcendent of that Divine Being. It concerns us, then, to try to see and say, for ourselves and as far as such matters may be told, how the Beauty of the divine Intellect and of the Intellectual Kosmos may be revealed to contemplation.

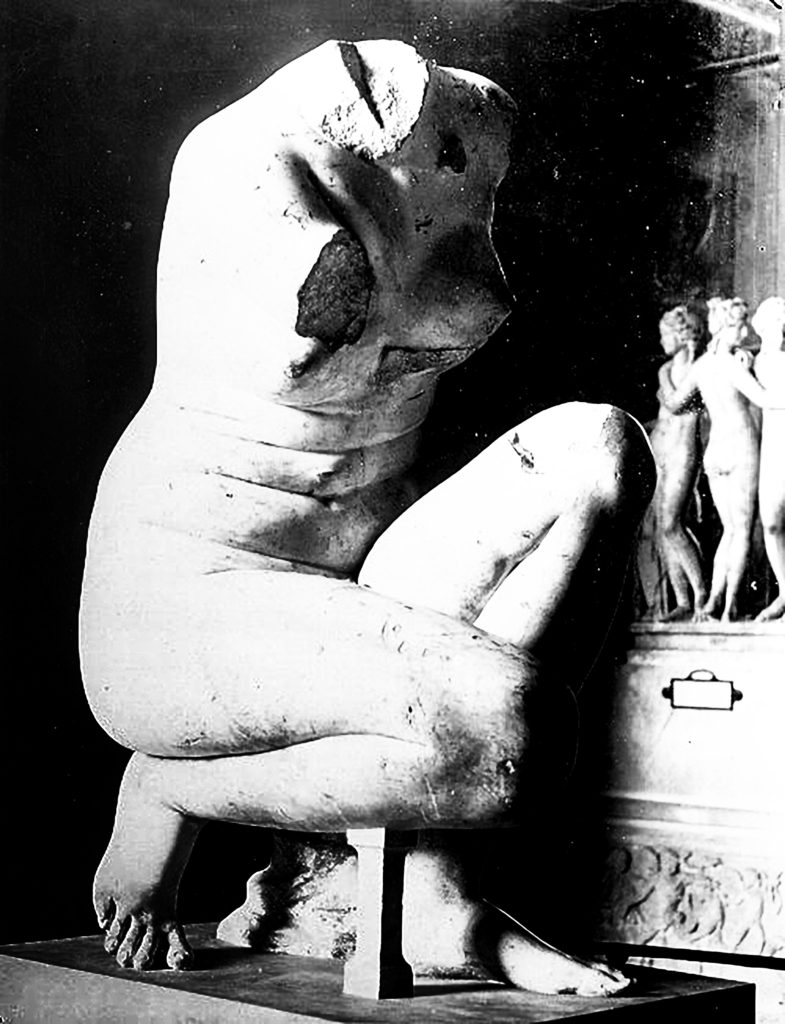

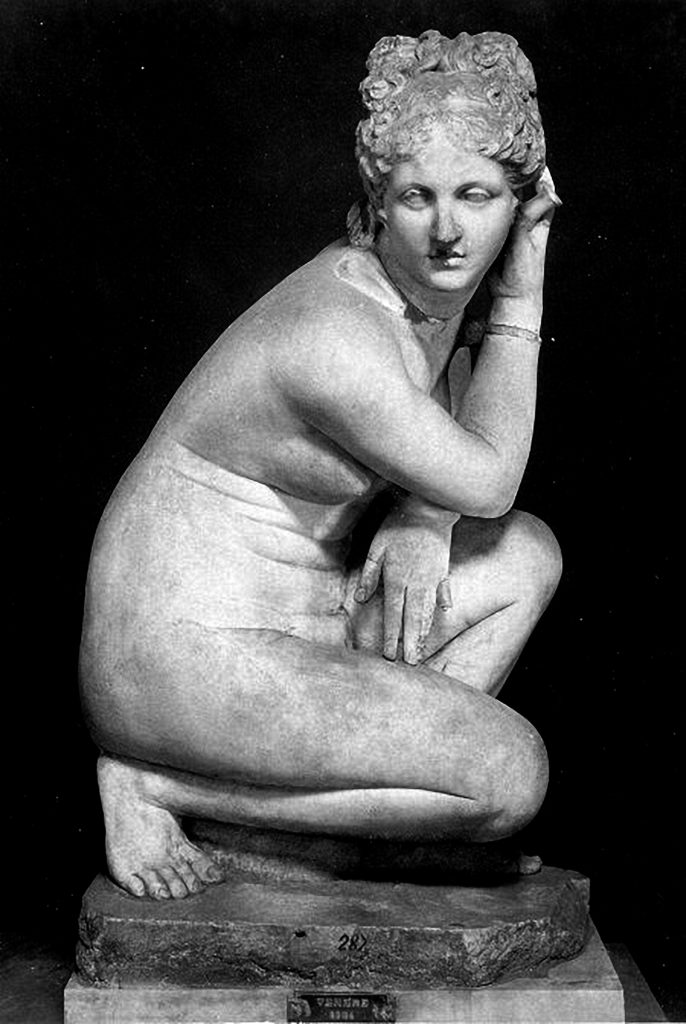

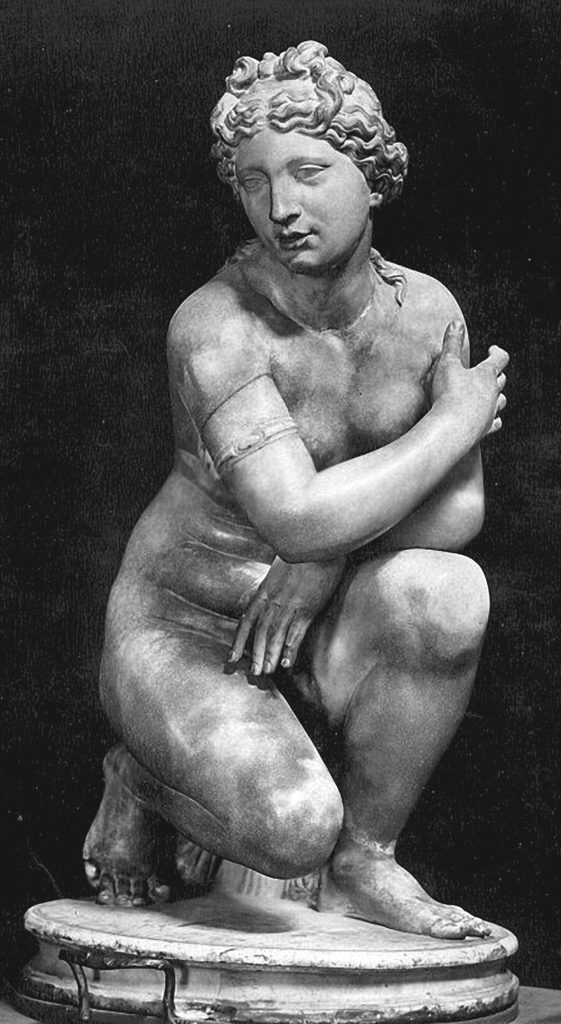

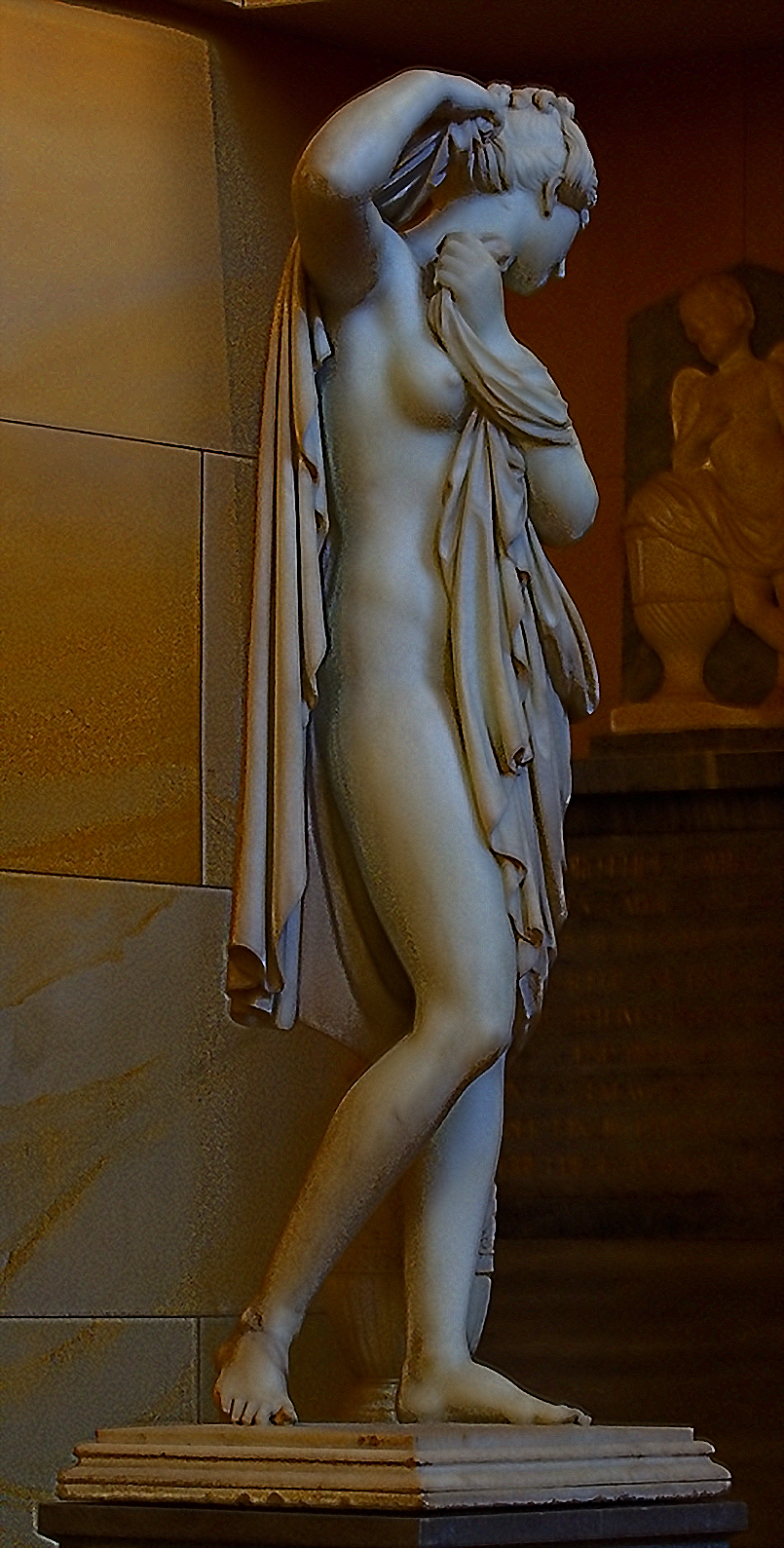

Let us go to the realm of magnitudes: Suppose two blocks of stone lying side by side: one is unpatterned, quite untouched by art; the other has been minutely wrought by the craftsman’s hands into some statue of god or man, a Grace or a Muse, or if a human being, not a portrait but a creation in which the sculptor’s art has concentrated all loveliness.

Now it must be seen that the stone thus brought under the artist’s hand to the beauty of form is beautiful not as stone- for so the crude block would be as pleasant- but in virtue of the form or idea introduced by the art. This form is not in the material; it is in the designer before ever it enters the stone; and the artificer holds it not by his equipment of eyes and hands but by his participation in his art. The beauty, therefore, exists in a far higher state in the art; for it does not come over integrally into the work; that original beauty is not transferred; what comes over is a derivative and a minor: and even that shows itself upon the statue not integrally and with entire realization of intention but only in so far as it has subdued the resistance of the material.

Art, then, creating in the image of its own nature and content, and working by the Idea or Reason-Principle of the beautiful object it is to produce, must itself be beautiful in a far higher and purer degree since it is the seat and source of that beauty, indwelling in the art, which must naturally be more complete than any comeliness of the external. In the degree in which the beauty is diffused by entering into matter, it is so much the weaker than that concentrated in unity; everything that reaches outwards is the less for it, strength less strong, heat less hot, every power less potent, and so beauty less beautiful.

Then again every prime cause must be, within itself, more powerful than its effect can be: the musical does not derive from an unmusical source but from music; and so the art exhibited in the material work derives from an art yet higher.

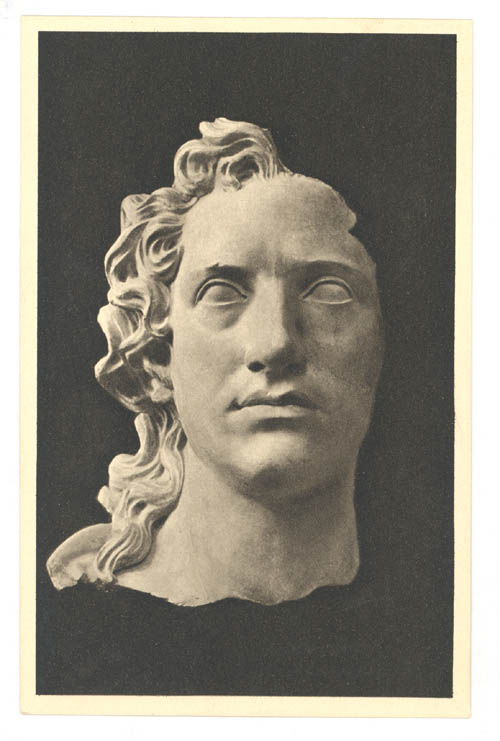

Still the arts are not to be slighted on the ground that they create by imitation of natural objects; for, to begin with, these natural objects are themselves imitations; then, we must recognize that they give no bare reproduction of the thing seen but go back to the Ideas from which Nature itself derives, and, furthermore, that much of their work is all their own; they are holders of beauty and add where nature is lacking. Thus Pheidias wrought the Zeus upon no model among things of sense but by apprehending what form Zeus must take if he chose to become manifest to sight.

Plotinus was the founder of Neoplatonism, the dominant philosophical movement of the Graeco-Roman world in late antiquity, and the most significant thinker of the movement. He is sometimes described as the last great pagan philosopher. His writings, the so called

Enneads, are preserved as whole. While an earnest follower of Plato, he reveals other philosophical influences as well, in particular those of Aristotle and Stoicism. Plotinus developed a metaphysics of intelligible causes of the sensible world and the human soul. The ultimate cause of everything is ‘the One’ or ‘the Good’. It is absolutely simple and cannot be grasped by thought or given any positive determination. The One has as its external act the universal mind or ‘Intellect’. The Intellect’s thoughts are the Platonic Forms, the eternal and unchanging paradigms of which sensible things are imperfect images. This thinking of the forms is Intellect’s internal activity. Its external act is a level of cosmic soul, which produces the sensible realm and gives life to the embodied organisms in it. Soul is thus the lowest intelligible cause that immediately is immediately in contact with the sensible realm. Plotinus, however, insists that the soul retains its intelligible character such as nonspatiality and unchangeability through its dealings with the sensible. Thus he is an ardent soul-body dualist. Human beings stand on the border between the realms: through their bodily life they belong to the sensible, but the human soul has its roots in the intelligible realm. Plotinus sees philosophy as the vehicle of the soul’s return to its intelligible roots. While standing firmly in the tradition of Greek rationalism and being a philosopher of unusual abilities himself, Plotinus shares some of the spirit of the religious salvation movements characteristic of his epoch.

6. Human beings

A noteworthy feature of Plotinus’ psychology is his use of Aristotelian machinery to defend what is unmistakably Platonic dualism. For instance he uses the Aristotelian distinctions between rational, perceptive and vegetative soul much more than the tripartition of Plato’s Republic (see

Psych ). He employs the Aristotelian notions of power (dynamis) and act (energeia), and sense perception is described very much in Aristotelian terms as the reception of the form (eidos) of the object perceived (see

Aristotle §18). However, he never slavishly follows Aristotle and the reader should be prepared for some modifications even where Plotinus sounds most Aristotelian.

Plotinus identifies human beings with their higher soul, reason. The soul, being essentially a member of the intelligible realm, is distinct from the body and survives it. It has a counterpart in Intellect which Plotinus sometimes describes as the real human being and real self. As a result of communion with the body and through it with the sensible world, we may also identify ourselves with the body and the sensible. Thus, human beings stand on the border between two worlds, the sensible and the intelligible, and may incline towards and identify themselves with either one. For those who choose the intelligible life, philosophy (dialectic) is the tool of purification and ascent. As noted previously, however, it is possible to ascend beyond the level of philosophy and arrive at a mystical reunion with the source of all, the One. In contrast with the post-Porphyrian Neoplatonists, who maintained theurgy as an alternative, Plotinus stands firmly with classical Greek rationalism in holding that philosophical training and contemplation are the means by which we can ascend to the intelligible realm.

Plotinus’ account of sense perception is an interesting example of how he can be original while relying on tradition. Sense perception is the soul’s recognition of something in the external sensible world. The soul alone only knows intelligibles and not sensibles. If it is to come to know an external physical object it must somehow appropriate that object. On the other hand, action of a lower level on a higher is generally ruled out and a genuine affection of the soul is impossible because the soul is not subject to change. Plotinus proposes as a solution that what is affected from the outside is an ensouled sense organ, not the soul itself. The affection of the sense organ is not the perception itself however, but something like a mere preconceptual sensation. The perception properly speaking belongs to the soul. It is a judgment (krisis) or reception of the form of the external object without its matter. This judgment does not constitute a genuine change in the soul for it is an actualization of a power already present. In formulating this problem Plotinus’ dualism becomes sharper, and in some respects closer to Cartesian dualism, than anything found in Plato or previous ancient thinkers. Plotinus contrasts sense perception as a form of cognition with Intellect’s thought, which is the paradigm and source of all other forms of cognition. Sense perception is in fact a mode of thought but it is obscure. This is because the senses do not grasp the ‘things themselves’, the thoughts on the level of Intellect, but mere images. Since they are images they also fail to reveal the grounds of their being and necessary connections.

As the preceding account may suggest, Plotinus sees the goal of human life in the soul’s liberation from the body and from concerns with the sensible realm and identification with the unchanging intelligible world. This is in outline the doctrine of Plato’s middle dialogues. There are noteworthy elaborations, however. Plato holds that the soul’s ability to know the Forms shows its kinship with them (Phaedo 79c-e). Plotinus agrees and presents a doctrine about the nature of this kinship which is left unclear in Plato. For as we have seen the whole realm of Forms is for Plotinus the thought of Intellect. The human soul has a counterpart in Intellect, a partial mind which in fact is the true self and is that on which the soul depends. This has two interesting consequences for the doctrine of spiritual ascent: (1) the soul’s ascent may be correctly described as the search after oneself and, if successful, as true self-knowledge, as fully becoming what one essentially is; (2) on account of Plotinus’ doctrine about the interconnectedness of Intellect as a whole, gaining this self-knowledge and self-identity would also involve gaining knowledge of the realm of Forms as a whole.

Plotinus’ views on classical Greek ethical topics such as virtues (see

Aret) and happiness (see

Eudaimonia) are determined by his general position that intellectual life is the true life and proper goal of human beings. He devotes one treatise,

I 2(19), to the virtues. The suggestion in Plato’s Theaetetus (176a-b) that the virtues assimilate us with the divine is central to his views on them, and serves as his point of departure. The question arises how to reconcile this doctrine with the doctrine of the four cardinal virtues in the Republic. Plotinus distinguishes between political virtues, purgative virtues and the paradigms of the virtues at the level of Intellect. These form a hierarchy of virtues. The function of the political virtues (the lowest grade) is to give order to the desires. It is not clear, however, how these can be said to assimilate us to god (Intellect), for the divine does not have any desires that must be ordered and hence cannot possess the political virtues. Plotinus’ answer is that although god does not possess the political virtues, there is something in god answering to them and from which they are derived. Furthermore, the similarity that holds between an image and the original is not reciprocal. Thus, the political virtues may be images of something belonging to the divine without the divine possessing the political virtues.

There are two treatises dealing with happiness or wellbeing: I 4(46) and I 5(36). In the former treatise Plotinus rests his own position on Platonic and Aristotelian doctrines, while criticizing the Epicureans and Stoics. He rejects the view that happiness consists at all in pleasure, a sensation of a particular sort: one can be happy without being aware of it. He also rejects the Stoic account of happiness as rational life. His own position is that happiness applies to life as such, not to a certain sort of life. There is a supremely perfect and self-sufficient life, that of the Intellect, upon which every other sort of life depends. Happiness pertains primarily to this perfect life that is in need of no external good. Since all other kinds of life are reflections of this one, all living beings are capable of at least a reflection of happiness according to the kind of life they have. Human beings are capable however of attaining the perfect kind of life, that of Intellect. In the latter treatise Plotinus holds with the Stoics that none of the so-called ‘external evils’ can deprive a happy person of their happiness and that none of the so-called ‘goods’ pertaining to the sensible world are necessary for human happiness (see

Stoicism §§15-17). In I 5 he argues that the length of a person’s life is not relevant to happiness. This is because happiness, consisting in a good life, is the life of Intellect and this life is not dispersed in time but is in eternity, which here means outside time.

7. Influence

Plotinus is one of the most influential of ancient philosophers. He shaped the outlook of the later pagan Neoplatonic tradition, including such thinkers as Porphyry and

Proclus, and he left clear traces in Christian thinkers such as Gregory of Nyssa (see

Patristic philosophy §5),

Augustine and

Boethius. Since all these were extremely influential in their own right, Plotinus has had great indirect impact. He clearly played a significant role in preparing for medieval philosophical theology. A forged extract from the

Enneads was known in the Islamic world as the

Theology of Aristotle. The supposed Aristotelian origin of this text helped the fusion of Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism that characterizes much of Arabic philosophy. Neoplatonism saw a revival in Europe during the Renaissance. A Latin translation of the

Enneads by Marsilio

Ficino first appeared in 1492 and gained wide distribution. Plotinus exerted considerable direct influence on many sixteenth-and seventeenth-century intellectuals. Even if the popularity of Neoplatonism and Plotinus receded in the seventeenth century, many individual thinkers since have read and been influenced by Plotinus, for instance

Berkeley,

Schelling and

Bergson.

EYJÓLFUR KJALAR EMILSSONCopyright © 1998, Routledge.;

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Modern Aesthetics

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant was concerned with judgments of taste. Objects are judged beautiful, he proposed, when they satisfy a disinterested desire: one that does not involve personal interests or needs. It follows from this that beautiful objects have no specific purpose and that judgments of beauty are not expressions of mere personal preference but are universal. Although one cannot be certain that others will be satisfied by objects he or she judges to be beautiful, one can at least say that others ought to be satisfied. The basis for one’s response to beauty exists in the structure of one’s mind.

Art should give the same disinterested satisfaction as natural beauty. Paradoxically, art can accomplish one thing nature cannot. It can offer ugliness and beauty in one and the same object. A fine painting of an ugly face is nonetheless beautiful.

According to the 19th-century German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, art, religion, and philosophy are the bases of the highest spiritual development. Beauty in nature is everything that the human spirit finds pleasing and congenial to the exercise of spiritual and intellectual freedom. Certain things in nature can be made more congenial and pleasing, and it is these natural objects that are reorganized by art to satisfy aesthetic demands.

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed that the forms of the universe, like the eternal Platonic forms, exist beyond the worlds of experience, and that aesthetic satisfaction is achieved by contemplating them for their own sakes, as a means of escaping the painful world of daily experience.

Fichte, Kant, and Hegel are in a direct line of development. Schopenhauer attacked Hegel but was influenced by Kant’s view of disinterested contemplation. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche followed Schopenhauer at first, then disagreed with him. Nietzsche concurred that life is tragic, but thought that this should not preclude acceptance of the tragic with joyous affirmation, the full realization of which is art. Art confronts the terrors of the universe and is therefore only for the strong. Art can transform any experience into beauty, and by so doing transforms its horrors in such a way that they may be contemplated with enjoyment. Although much modern aesthetics is rooted in German thought, German thinking was subject to other Western influences. Lessing, a founder of German romanticism, was affected by the aesthetic writings of the British statesman Edmund Burke.

Aesthetics and Art

Traditional aesthetics in the 18th and 19th centuries was dominated by the concept of art as imitation of nature. Novelists such as Jane Austen and Charles Dickens in England and dramatists such as Carlo Goldoni in Italy and Alexandre Dumas fils in France presented realistic accounts of middle-class life. Painters, whether neoclassical, such as J. A. D. Ingres, romantic, such as Eugène Delacroix, or realist, such as Gustave Courbet, rendered their subjects with careful attention to lifelike detail.

In traditional aesthetics it was also frequently assumed that art objects are useful as well as beautiful. Paintings might commemorate historical events or encourage morality. Music might inspire piety or patriotism. Drama, especially in the hands of Dumas and Henrik Ibsen, a Norwegian, might serve to criticize society and so lead to reform.

In the 19th century, however, avant-garde concepts of aesthetics began to challenge traditional views. The change was particularly evident in painting. French impressionists, such as Claude Monet, denounced academic painters for depicting what they thought they should see rather than what they actually saw—that is, surfaces of many colors and wavering forms caused by the distorting play of light and shadow as the sun moves.